Over at my Substack I’ve spent more than a year writing about the cultural and genetic impact of the Eurasian steppe. I’ve put out a large number of essays, so I want to post them here in case you missed one. In reverse order…

A Hun by any other name – On the genetic trail of Europe’s enduring bête noire:

The specter of these pitiless barbarians swooping in on horseback had haunted the ancients, their horror recorded in histories that filtered down to modern Europeans. In these classical texts, the Huns were the epitome of brutal and alien savages whose raison d’etre was total victory on the battlefield, punctuated by gluttonous orgies of flesh, food and drink. They were the embodiment of the European cultural imagination’s bête noire, the austere and erudite Roman aristocrat contrasting sharply with the brutish barbarian guzzling mare’s milk and gnawing on a hunk of raw meat while in the saddle.

The wolf at history’s door and Casting out the wolf in our midst are more anthropological and focused on the koryos and their role in shaping Eurasian history. I count these two as steppe-adjacent since they lack the chronological focus of the other pieces.

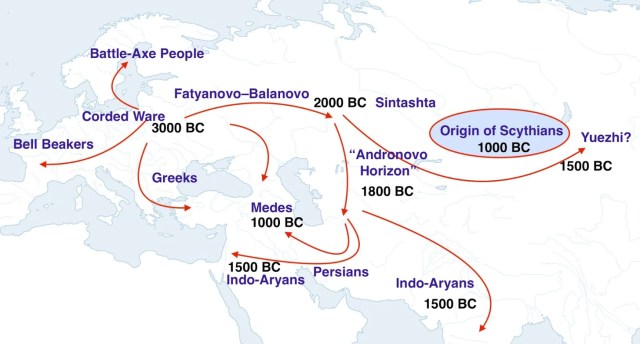

Dark Horse out of the Steppe Fishing the Sintashta, Scythians and Sarmatians out of obscurity.

The Yamnaya-powered transformation of Europe and Asia more than 5,000 years ago was a social and economic revolution, with the explosion of nomadic pastoralism across the Eurasian steppe. Its downstream linguistic and cultural consequences are with us to this very day: billions of us speak Indo-European languages, and we preserve those ancestral religious beliefs both in the shared mythology of the West and in the living religious traditions of India. To premodern minds untouched by science, the rise of obscure tribes to world conquest would have been evidence of divine providence and fate. Theirs was a world of miracles, and the gods always chose favorites. By the 20th century, supernatural explanations had foundered on the shoals of scientific materialism. But unless you were a Marxist, history was a matter of narrow description of particular places and times, rather than general theoretical narratives that explained the arc and ebb of societies and cultures. It was one damn thing after another, with broader patterns attributed to the vague laws of probability.

Hungarians as the ghost of the Magyar confederacy: The cultural legacy of the Magyars far outweighs their genetic impact. Another steppe-adjacent piece, though this one focuses on one nation so it’s more appropriate.

Steppe 1.1a: A nowhere man’s world and Steppe 1.1b: culture vultures descend are two posts about the Corded Ware, Bell Beakers, and the steppe intrusion into Europe.

Steppe 1.0, Going Nomad: The early Indo-Europeans’ great leap forward:

Today 3.5 billion humans speak Indo-European languages, which dominate Eurasia from Spain to the Indian subcontinent. This is the legacy of the pastoralists who roamed the Pontic steppe north of the Black sea 5,000 years ago. They were the original Indo-Europeans. They pioneered the nomadic lifestyle, leaving behind hard toil at the plow and thankless foraging in cold Siberian forests. They chose instead to wander the open grasslands in search of fresh pastures for their herds. They were the first to unleash young warriors raised as roving nomads upon the world, predatory packs marching the breadth of a continent in a few centuries. We don’t know what they called themselves. We don’t know the names of those who led them. But their cultural innovations and the choices they made transformed our world and made us who we are today. These nameless people left no monuments or seminal texts. Instead, we live with their language, their gods and their genes.

Finally, the two introductory posts, Entering Steppelandia: pop. 7.7 billion: Why the steppe matters to me, and why it should matter to you and Library of the Steppe: They didn’t read, but you should.