|

Thursday, March 29, 2007

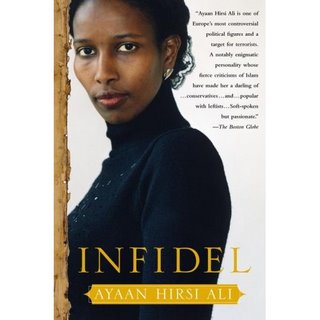

Note from Razib: This discussion thread will be heavily moderated. If you're not going to be interesting, be banal and polite. Otherwise, be interesting. My point in Islam threads isn't to sit there listening to self-important prigs repeat the same talking points I've heard since 9/11. Been there, done that (myself). Let's add some value. Note from Razib: This discussion thread will be heavily moderated. If you're not going to be interesting, be banal and polite. Otherwise, be interesting. My point in Islam threads isn't to sit there listening to self-important prigs repeat the same talking points I've heard since 9/11. Been there, done that (myself). Let's add some value.End Note Reviewers of Hirsi Ali's autobiography, Infidel, should be required to put relevant cards on the table. Accordingly, here are mine: I am a reluctant atheist, which I mean that I wish I could believe in some comforting suprapersonal code, but I don't (and I have a particular contempt for the latterday "god of the gaps"); that said, I am nervous about and wary of Islam finding a beachhead in the West, even as I reject anguished warnings of the immanence of Eurabia and creeping dhimmitude. Also, I had no particular interest in reading Hirsi Ali's book. (Parenthetically, I knew of her long before the Theo Van Gogh murder, and it occurred to me when I first heard of her and apprehended her striking physical presence, that she would eventually end up in the United States. I did not, of course, foresee the terrible events that precipitated her move, but I suspected that Holland was simply too small a country to contain her.) I have so far been unimpressed by the intellectual calibre of other Muslim critics. They have zero credibility in the Muslim world and their criticisms of Islam may be valid but the only noteworthy thing about them is that they are undergoing enlightenment two centuries after it became unremarkable in the West. I sympathize, but for my crowd, the thrill is gone. What sparked my interest in reading Hirsi Ali's was a fierce irritation at the constant references to religion in American public life since 9/11. This was bad enough when the hectoring came from the right, but now it's coming from the left. I could and did ignore the Baptist who said that god doesn't hear the prayers of a Jew, because he's a hick that no one in the cultural elite, among whom I live and work, takes seriously. I don't pray and I don't care. I scorned the leftists who brandished this nobody in my face as an example of the horrors of American anti-Semitism, when it was nothing of the sort. Now these same people go on Air America to tell the world that Jesus was a leftist (no links, but I heard it) and they supply ludicrous, a-historical examples to prove their non-existent case. This "who can be more sanctimonious" religious competition is driving me crazy, but it has had the salutary effect of clarifying my attitudes. So I paid renewed attention to this literal firebrand. I wanted to see if I could learn anything from her book than the fact that another smart girl grew up and left god-as-daddy with her dolls. I did. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, I am pleased to report, is a much more interesting, deep (and flawed, like all heroic figures) person than any collection of newspaper reports can convey. Those looking for a simple "I hate Islam" manifesto will be disappointed by Infidel. The book -- which should more properly be called "Apostate"-- is a calm, lucid, balanced account of a nightmarish upbringing. She wasn't really raised, as Westerners understand it, she just grew taller while being dragged around to various third world hellholes (Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and then Nairobi), due to her father's clan-based opposition to Somali dictator Siad Barre. Hirsi Ali's mother, grandmother, older brother and younger sister existed on charity doled out by her father's clan members. Hirsi Ali watched her once-vibrant and enterprising mother become distorted with bitterness, subjecting Hirsi Ali's to routine beatings, while turning her outwardly docile middle child into the family drudge. It is revealing that Ayaan Hirsi Ali divides her autobiography into two parts, entitled "My Childhood," and "My Freedom." The animating force of her life is to tell the world that Islam is essentially infantilizing. The first half of the book, which encompasses the first 22 years of her life, is riveting reading. She describes the ideal of Somali womanwood: to be baarri, whose closest approximation in English would be virtue: "If you are a Somali woman you must learn to tell yourself that God is just and all-knowing and will reward you in the Hereafter." Hirsi Ali explains: "If her husband is cruel, if he rapes her and then taunts her about it, if he decides to take another wife, or beats her, she lowers her gaze and hides her tears. And she works, faultlessly." Have you ever wondered about the bewildering complexity of Somalia's clan structure? This is the book for you. Somali life, as she describes it, consists of complete, utter, subservience to family and clan, yet it is pervaded by suspicion and violence. When she is a little girl, her one-year older brother pushes her into a shit-filled latrine. And whose fault is it? Ayaan's, because she failed to be suspicious. It's a world where feelings are considered weakness, and pride is everything. No review can do justice to how crowded with incident and packed with colorful, fantastic characters the first half of the book is. She is moved from Saudi Arabia to Ethiopia to a series of dwellings in Nairobi. She and her younger sister are gentially mutilated by their nomad-born grandmother. She learns Arabic, Amharic, English and Swahili. She becomes infatuated with Islamic fundamentalism but describes the process as so natural we never question its inevitability. A crazed Quran teacher shoves her head against a wall and fractures her skull; the hospital costs are covered by (what else?) the clan. Other wandering preachers of Islam drift in and out of the exile Somali community. She elopes with a gorgeous cousin strictly for the sex; they ditch each other quickly and figure out a way to "unmarry" each other. (Hint: the clan works out the details.) She rescues family members streaming out of Mogadishu by bribing Kenyan border police. This is all portrayed expertly, with deft omissions (to keep the story in control; whole books could be written about the era of African history she witnessed), swift pacing, and tight narrative. The amount of human suffering that Hirsi Ali witnesses in Africa is sometimes overwhelming, and one wonders whether the second part of the book doesn't show evidence of some post-traumatic stress disorder. As Ian Buruma points out, her account of Dutch life is a bit too pat, too admiring. But should we not empathize with Hirsi Ali? after living the life she has, and witnessing what she has, Holland is a paradise. But, as she herself points out, it's a hard-won paradise, created by centuries of conflict between Catholic and Protestant, reclaimed from the sea. Her Dutch experience sounds reported and not fully lived, as her life in Africa was. (Perhaps this is true of the difference between life in Africa and life in Europe and has nothing to do with Hirsi Ali's specific experience -- I report, you decide.) In Holland, Hirsi Ali committed two signal mistakes. The first was that she fabricated the reasons for claiming asylum in Holland. The fabrications were minor and were common knowledge, but her status could and should have been legally regularized before she stood for Parliament. More seriously, Hirsi Ali's collaboration with Theo Van Gogh on Submission occurred after she was elected to Parliament. Van Gogh's November 2004 murder was not her fault, but Hirsi Ali was a public servant at the time, and would have done her cause of protecting Muslim women greater service by focusing on the passage of laws to protect them, than by auditioning to be the Karen Finlay/Andres Serrano of Holland. These judgement mistakes made her vulnerable to a Swift Boat slandering on a Dutch television show from which her reputation suffered. Family members denied that Hirsi Ali was forced into an arranged marriage and was not genitally mutilated. These slanders continue to be retailed in the Muslim blogosphere and are thoroughly and convincingly refuted in the book. No one who reads the description of her mutilation can doubt that she experienced this horrific abuse; her detailing of the arranged marriage is as watertight as the grass jugs her grandmother used to weave by hand. Hirsi Ali isn't the first prophet to experience dishonor in her country. What she can do to modernize and moderate Islam is doubtful, as she is now by public profession no more a part of the Ummah. She's our girl now and part of our furious debate about how to get along with Islam. The same neoconservatives whose chief guru cynically valued religion as social control for dummies have insincerely gushed over her book not because she has embraced enlightenment, but because she has rejected Islam. Hirsi Ali thinks the West is falling apart. I disagree: we've never had it so good, and it's getting better all the time. She thinks that Muslims will destroy the West with higher birthrates: I doubt this. Pim Fortuyn favored a Cold War with Islam. I don't think that's necessary. However, Fortuyn also said, "I don't want to fight for the rights of women and homosexuals again," and that, I think, is the heart of the issue, although I wouldn't put it that way. Here's how I would put it: "the law of the land is the law." Those of you who wish to keep your youth Muslim and live in the West must figure out a way to reconcile Islam with the dominant culture. If you can't, expect more Hirsi Alis. In fact, expect more Hirsi Alis even if you do -- it's the price of the ticket. The stupid among your children will be seduced by bling; the brilliant, by science. And, unlike the chicken littles of the Right blogosphere, I think that is exactly what we are saying, if rather mumblingly, hesitantly and stammeringly. Sometimes, it's not way you say, it's what you do. That Puerto Rican girl on the subway isn't exchanging her t-shirt that says, "I must, I must, I must improve my bust," for a burqa. Our industrialists and molecular biologists and physicists aren't going to stop thinking and innovating and creating. They are an army much more powerful than the Quran, yes. We will insist, acidly, on our freedoms, on our laws, on our science, and our crummy t-shirts. If the Muslims in our midst can't handle it, that's their problem. The fact that Hirsi Ali needs bodyguards is disgusting and unacceptable but it is evidence of Islam's fragility, not our weakness. Finally, we will protect the apostates from Islam who come to our free societies for refuge. If Hirsi Ali has helped us to focus our minds on that task, she deserves our gratitude. |