|

Thursday, July 28, 2005

On many measures, identical (monozygotic, MZ) twins are not in fact "identical", despite the fact that they share essentially identical DNA and highly similar family environments. Indeed, for some traits, such as personality, all non-genetic effects appear to be of the kind that makes siblings different than one another. Peer socialization is one plausible source of this non-shared environment, but stochastic biological events probably play a role as well.

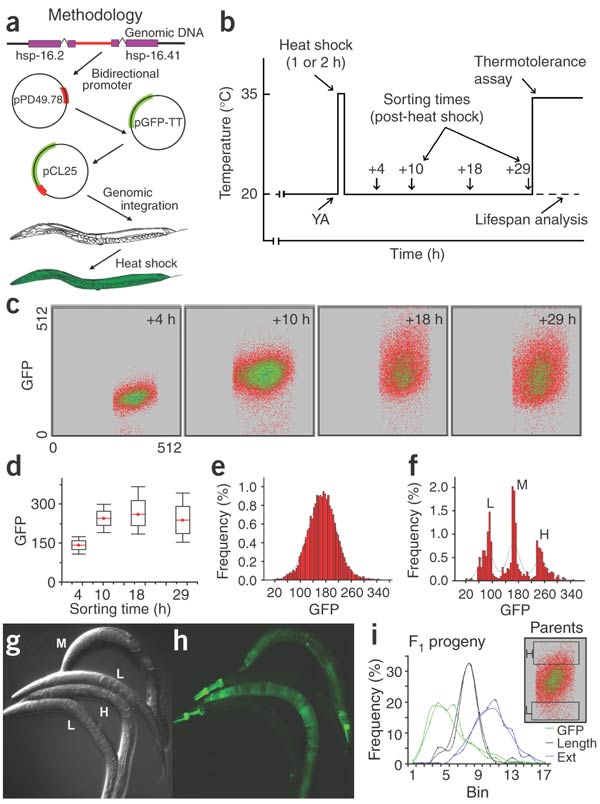

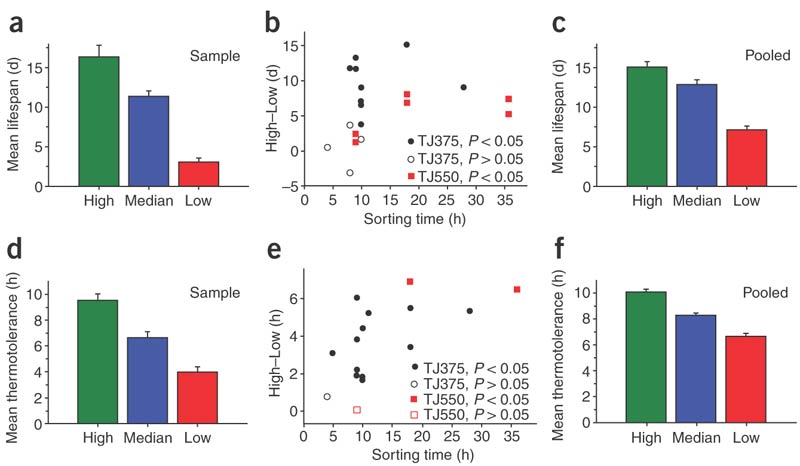

These stochastic effects are seen prominently in studies of aging in the worm C. elegans. Even when genes and environment are held constant[1], there is considerable variation in lifespan (time of death) within a population. (Almost as much variation in relative lifespan as the human population of the US.) A paper published this week in Nature Genetics (ironic) reports that chance variation in the level of induction of a stress-induced reporter predicts (to some extent) variation in lifespan. When both genotype and environment are held constant, 'chance' variation in the lifespan of individuals in a population is still quite large. Using isogenic populations of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, we show that, on the first day of adult life, chance variation in the level of induction of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter coupled to a promoter from the gene hsp-16.2 predicts as much as a fourfold variation in subsequent survival. The same reporter is also a predictor of ability to withstand a subsequent lethal thermal stress. The level of induction of GFP is not heritable, and GFP expression levels in other reporter constructs are not associated with differences in longevity. HSP-16.2 itself is probably not responsible for the observed differences in survival but instead probably reflects a hidden, heterogeneous, but now quantifiable, physiological state that dictates the ability of an organism to deal with the rigors of living. The astonishing implication is that similar reporters could be found that predict the chance variation in human lifespan (or other dimensions of human biodiversity). How did they do this research? First, they created a strain of worm which fluoresces in response to exposure to high temperatures ("heat shock") (panel "a" below). The "heat-shock gene" hsp-16.2 is expressed when worms are heat shocked. The promoter of hsp-16.2 was joined with the protein coding sequence of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and this construct was integrated into the worm's genome. The intensity of GFP expression (measured by fluorescent intensity) is variable within an isogenic population (panel e). For their experiments, young adult worms were exposed to a heat shock (panel b) and then some time later they the worms were sorted into high, medium and low GFP subpopulations (panels f-h). The level of GFP expression becomes more variable at later times (panels c-d). The GFP expression level is not heritable: the progeny of worms from the high and low groups are indistinguishable when tested for GFP induction.  After sorting into three subpopulations, worms were tested for lifespan (panels a-c) or thermotolerance (i.e., lifespan at high temperature; panels d-f).  Numerous controls follow. The biggest problem for their study is that heat shock is known to cause increased lifespan on its own. They don't claim to have overcome this confounding effect, and so it seems to me that differential GFP expression may actually be a marker for this effect. 1 - C. elegans has two sexes: male and hermaphrodite. Hermaphrodites are self-fertilizing. Selfing allows for the production of genetically homogenous populations (except random mutations). Worms are grown on solid media in Petri dishes ("plates") or in liquid cultures. Worms living on the same plate are essentially experiencing the same environment, but undetected variation may exist between different plates or within different regions of the same plate. |