|

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Peep the structure of a whole empire. - Malik B

I have a couple of nice papers here looking at the inter-relation between LTP, actin polymerization, and dendritic spine structure. They are both pretty dense, so I'll do a single post on this Fukazawa et al. paper (pdf) and then, with the conceptual junk already on board, its should be easy to present the information form this later study by Okamoto et al. The majority of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus occurs at dendritic spines. There appear to be specialized structural components on both the sending (pre-synaptic active zone) and receiving (spine, post-synaptic density) sides of a synapse that mediate efficient transmission. Modification of this structure provides a highly plausible mechanism for enhancing or diminishing the connection between two neurons in a lasting way. There is an intimate relationship between the structure of the spine and actin polymerization within the spine. Actin is a cytoskeletal protein with the ability to form long filaments to which other proteins can bind and interact in complexes. It is really remarkable that actin forms in integral part of synaptic protein complexes and helps to determine structure considering that the actual subunits that make up an actin filament turnover really quickly. According to Fukazawa et al., over 80 percent of actin in dendritic spines turns over in less than a minute. This makes one have to shift perspective a little bit and deal with actin as a dynamic process. All of the things actin does when it forms filaments must be regulated by altering the rate of polymerization or depolymerization rather than by a single polymerization event that is maintained once organized. Fukazawa et al. suggest a number of ways in which LTP might be realized through actin structure modification:

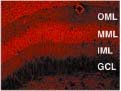

If this were a journal club talk I would be enjoined to get to the data already, but I have a couple more things you have to understand to get the paper, and I think it is interesting so you have to bear with me. In this Fukazawa et al. paper the LTP they are studying is actually done in a live animal. Most of the experiments involve inducing LTP via a specific pathway, and then staining the hippocampus to determine the state of actin. Actin can is found in two forms, globular (G-actin) and filamentous (F-actin). Death cap mushrooms make a poison called phallotoxin or phalloidin that binds to F-actin and not G-actin. The authors have phalloidin conjugated to a fluorescent molecule, so they can stain hippocampi and look for F-actin, indicating an increase in polymerization. The other cool thing is the specificity of the pathways they are stimulating. LTP was induced either by stimulation of the medial (MPP) or lateral perforant path (LPP) which project from the medial (MEC) and lateral entorhinal cortices (LEC) respectively. Others have shown that the MEC is specialized for representing spatial information while the LEC is more responsible for the non-spatial input into the hippocampus. The potentials generated in the hippocampus by these inputs generate different types of traces. LPP potentials tend to take longer to peak and last longer. The LPP and MPP both synapse in the same subregion of the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, but they synapse on different parts of the dendrites of dentate gyrus cells (the outer molecular layer (OML) and middle molecular layer (MML) respectively, shown below. The LPP input synapses on dendrites further away from the cell body than does the MPP input. I find this intriguing because I also recently read that spines far away from the soma have thinner necks and are less able to diffuse calcium that comes in through NMDA receptors. As we all know, calcium starts doing interesting things if it hangs out in a dendritic spine very long. On the other hand, where does the calcium that diffuses through a stubby-necked spine go…into the dendrite where it could influence protein synthesis? This generates all sorts of interesting ideas about how modulation of spatial input could influence plasticity at non-spatial synapses. Would spatial information be remembered in a longer-lasting but fuzzier manner than non-spatial information? Or would calcium influx due to spatial representation modulate the ability of dendritic potentials further away from the soma to induce action potentials?  Back to the paper. The initial set of experiments involved inducing LTP just through the MPP to alter the synapses in the middle molecular layer (MML) of the dentate gyrus on one side of the brain and looking at what happens to actin and spine structure. Here is just one picture of a hippocampus labeled with fluorescent phalloidin:  Note that things are much brighter particularly in the MML. The level of F-actin has increased in the input layer has increased 45 minutes after LTP induction. They go on to show that this increase is happening in dendritic spines. In parallel, the average length of synaptic apposition (basically how much contact between axon and spine) increases in the stimulated side of the hippocampus. One thing to note is that, at least at this early timepoint, the number of spines does not appear to change. Rather it is the structure of existing spines that is altered by LTP induction. LTP can be induced to varying degrees with more or less high-frequency stimulation (HFS). In vivo LTP can last several weeks if induced with enough juice to begin with. Fukazawa et al. have short (HFS 90) and long-term (HFS 500) plasticity inducing protocols similar to E-LTP vs. L-LTP or LTP 1 vs. LTP 2 etc etc.. HFS 90 produces LTP that lasts around a day. The F-actin increase is observed 45 minutes after HFS 90, but not 1 week later. HFS 500 produces LTP and an F-actin increase that are still going strong a week later. Actually the F-actin increase is still there five weeks later, which is a substantial portion of a rat lifespan. The initial increase in F-actin is NMDA receptor dependent. For long-lasting changes in synaptic strength, actin must be allowed to continually polymerize at a higher rate (or depolymerize at a slower rate). This change in polymerization rate is in part mediated by synthesis of new proteins since cycloheximide (a protein synthesis inhibitor) and latrunculin A (an actin polymerization inhibitor) have the same effect of allowing LTP that lasts up to 8 hours but blocking any longer-lasting changes. The understanding of this process goes even deeper in this paper. The authors identify a particular promoter of actin depolymerization named ADF-cofilin that is negatively regulated by phosphorylation by a kinase called LIMK-1. That is, more LIMK-1 activity equals more actin polymerization (through a double-negative of regulation steps). The authors show that ADF-cofilin phosphorylation is higher in the stimulated side, and blocking this phosphorylation shortens the length of LTP. I find this last little bit especially interesting because it allows me to integrate some information from the first paper showing microRNA regulation of neuronal processes in mammals. MicroRNAs are recently discovered short bits of non-coding RNA that specifically inhibit the translation (either through degradation or sequestration) of complementary RNAs. The importance of miRNAs in gene regulation is equal to or greater than that of transcription factors. The mRNA for LIMK-1 is inhibited by a dendritically localized miRNA called miR-134. Plasticity inducing signals release the LIMK-1 mRNA from inhibition so that LIMK-1 can be synthesized. It seems perfectly plausible to me that this one of the proteins that needs to be synthesized to produce long-lasting LTP. Synaptic stimulation would remove miR-134 from the picture. LIMK-1 is translated. It phosphorylates ADF-cofilin. Actin is allowed to polymerize at a higher setpoint. Spines grow and synaptic contact is increased. So the story goes. It is probably more complicated than I made it out to be, but I will go into some of the problems with interpreting this work when I do the Okamoto et al. paper. One issue is that actin is all over the cell, including the pre-synaptic compartment, so it is difficult to perform manipulations that specifically affect dendritic spines. |