|

Monday, May 22, 2006

Glove compartment, gotta get my cash. Cause the crooked cops’ll try to come up fast. - Chamillionaire

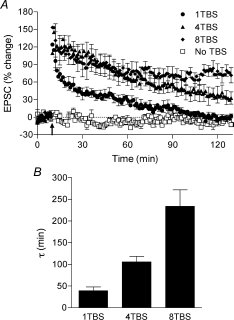

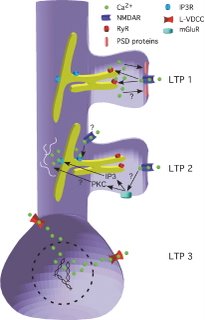

If you’re interested in the molecular mechanism of learning and memory, you read a lot about synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP).. If you’ve read anything at all about LTP, you’ve probably read that there is this special molecule called the NMDA receptor that serves as a “coincidence detector,” and allows neurons that are firing at the same time to increase their connection. The NMDA receptor is an ion-channel that, when coincident firing is detected, allows calcium to flow into the cell. Calcium inside the cell becomes more than just a charged molecule. It acts as a second messenger, binding to several enzymes and increasing or decreasing their activity. The signal transduction cascades that follow can lead to structural and biochemical modifications that increase the response to neurotransmitter release onto the stimulated synapse. The NMDA receptor, however, is not the whole story. There are numerous sources of calcium within and around a cell. This Journal of Physiology paper describes three of these other sources and dissects the role of each in determining the duration of changes in synaptic strength. LTP in the hippocampal slice is the model of choice for folks trying to figure out mechanisms of memory at a molecular level. It can be observed in plenty of other preparations, but the hippocampal slice far and away the most common. I think one of the reasons is that the hippocampus is a brain region known to play a role in the type of memory we refer to day-to-day: episodic memory, so if we can figure out how connections are made there, then we are closer to having memory with a capital ‘M’ figured out. Another reason is because it’s relatively convenient. To study LTP you need to be able to stick a stimulation electrode in one area and a recording electrode in another area that receives that stimulation. The hippocampus has a stereotyped circuit diagram in which these connected areas are easy to spot. To induce LTP, you use test-pulses to get a baseline and then shoot some intense stimulation in. After the high intensity stimulation, the response to test-pulses over at the recording electrode end increases. The observed increase is LTP. There is more than one type of LTP. One of the major distinctions has been between potentiation that requires new protein synthesis (translation) and lasts several hours (Late-LTP / LTP 2) and that that can be achieved with the proteins lying around already and lasts about 90 minutes (Early-LTP / LTP 1). The authors here make a further distinction for LTP that lasts even longer and requires synthesis of new mRNAs (LTP 3). The three LTP-types are induced in order of duration by increasing induction stimulations. LTP 1 is induced by a 1TBS protocol (theta-burst stimulation), LTP 2 by 4TBS, and LTP 3 by 8TBS. The number before “TBS” indicates the number of “shots“ the stimulation electrode is giving. The graph below shows the results of different induction protocols.  Okay, so here’s the awesome part. The three induction protocols specifically activate three different calcium sources that correspond to three different cellular compartments. The authors use pharmacology and calcium imaging to isolate the individual contributions. The calcium imaging is achieved using low-affinity calcium binding molecules that fluoresce when they bind and really high-resolution microscopy (two-photon). Here are the attributes of the three sources:

Inositol triphosphate (IP3) can be generated by metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) situated more peripheral to the synapse that are probably stimulated only when enough neurotransmitter is released to spill-over past the AMPA and NMDA-type receptors in the central part of the synapse. The IP3 binds to IP3-receptors in the ER out in the dendrite and induces calcium release. The VDCCs do what they say they should. Once the membrane potential at the cell soma reaches a sufficient depolarization these channels will open up and let calcium flow in right there next to the soma where it is ideally positioned to activate transcription factors and initiate mRNA synthesis. Put this all together, and you get a model like the authors proposed here:  One further thing I’d like them to investigate if they got the chance is the synapse-specificity of the LTP 3 that is generated in the presence of an NMDA receptor antagonist. It doesn’t appear immediately. Instead the synaptic strength slowly rises over the course of some thirty minutes. Since there is no special calcium signal happening at the particular stimulated synapse it seems like maybe this form of LTP is kind of a universal cell-wide potentiation. On the other hand, it could be that there is a local calcium-independent process that marks the stimulated synapses and allows specific potentiation. Retrospectacle had a brief discussion of some of this stuff related to long-term depression last week. Reference: Raymond CR. Redman SJ. 2006. Spatial segregation of neuronal calcium signals encodes different forms of LTP in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 570:97-111. |