|

Saturday, July 22, 2006

I'm finally shutting down the old website, but I thought it might be nice to have some of these older posts to link to. Plus I'm moving to NYC and writing up a thing for my actual work, so not as much time for original writing for a month or so. This was my first ever blog post (with slight modification).

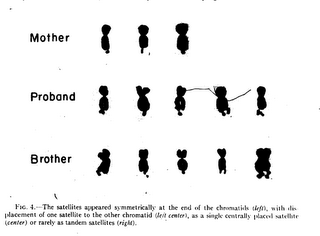

The title comes form Herbert Lubs, the first person to describe the chromosomal aberration for which Fragile X syndrome is named. The more extended quote goes "In one-third of the proband's metaphase figures, an unusual secondary constriction was seen at the ends of the long arm of a group C chromosome. This gave the appearance of large satellites, but the chromosome was never seen in association with the acrocentric chromosomes."  Part of the appeal of talking about Fragile X is that it covers so many levels of research. In this post, I'm going to give the basic features, a little history, and a little cytogenetics. I had planned on trying to explain why the Fragile X chromosome looks the way it does anyway, and it's fortuitous that there is an a blip on the chromosome radar coming up right as I prepare to do this. So without further ado, here's the litany of facts that you could've got if you'd only just googled Fragile X Syndrome:

Since I started off with the appearance of fragile X chromosomes I thought I'd try to explain why they look the way they do. This information was harder to find than I expected. It would appear that people are still working on this problem while I thought it would have been an almost immediate fallout from the discovery of the disease mechanism. Here's what I've got so far. "Microscopy" turned out to be a useful search term. First, there is a bit of an excuse to add a couple more pretty pictures. I found something of a methods paper describing a new way to mount chromosomes for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These authors don't waste any time theorizing or introducing or giving background information. They want everyone to be aware of this new awesome technique and that's it. So it's kind of hard to understand, but the gist of it is that not only can you see the fragile site on these X chromosomes depicted as a reduction in electron density at the boundary between the main chromosome and the satellite, but you can also see other pockets of reduced electron density throughout the satellite. The picture below shows the tip of a normal chromosome on the left and a fragile one on the right. See how the fragile one is less dense? They can even see this pattern at least one chromosome that doesn't show a fragile sight when they use regular fluorescence light microscopy which may indicate a burgeoning fragile site. My understanding is that low electron density means that there are less proteins there. This is consistent with the story from this other paper.  DNA during metaphase, which is when the pictures of chromosomes that you always see are taken, is coiled up and packed really tightly and part of the way this is achieved is to wrap the DNA strand around proteins complexes called nucleosomes. This is not the only case where DNA is wrapped around nucleosomes. It is pretty much happening all the time and DNA is getting wrapped and unwrapped all the time. Wang et al looked at the effect of having a bunch of CCGs repeated on this process. The way they did this was to mix small pieces of DNA (with or without a CCG repeats near one end) that were ostensibly not attached to any protein at the time with purified histones and let nature run its course. Then they took pictures with an electron microscope and counted places where nucleosomes had hooked up with the DNA. They found that while the distribution was fairly even across the non-CCG repeat DNA, there were hardly any nucleosomes at the location of the CCG repeats. So having a bunch of CCG's in a row makes it hard for nucleosomes to get involved. In fact, in later experiments, they found that nucleosome assembly was 62% less effective when there was a set of 76 repeated CCG's. They suggest that this leaves the DNA vulnerable to a process called methylation, by which one of those C's basically gets an extra carbon molecule sticking off of it that can alter the way the DNA interacts with proteins later on and lead to gene silencing. The consensus is that methylation is probably the mechanism by which the FMR1 gene gets turned off. One thing I'm not clear on is that I had thought that the way that methylation leads to gene silencing was by recruiting an enzyme that helps lead to nucleosome assembly on that particular chunk of DNA. The DNA wrapped around nucleosomes is relatively unavailable for transcription and therefore the gene is switched off. But in this case the methylation is supposed to be in conjunction with a lack of nucleosomes. How does that work? DNA during metaphase, which is when the pictures of chromosomes that you always see are taken, is coiled up and packed really tightly and part of the way this is achieved is to wrap the DNA strand around proteins complexes called nucleosomes. This is not the only case where DNA is wrapped around nucleosomes. It is pretty much happening all the time and DNA is getting wrapped and unwrapped all the time. Wang et al looked at the effect of having a bunch of CCGs repeated on this process. The way they did this was to mix small pieces of DNA (with or without a CCG repeats near one end) that were ostensibly not attached to any protein at the time with purified histones and let nature run its course. Then they took pictures with an electron microscope and counted places where nucleosomes had hooked up with the DNA. They found that while the distribution was fairly even across the non-CCG repeat DNA, there were hardly any nucleosomes at the location of the CCG repeats. So having a bunch of CCG's in a row makes it hard for nucleosomes to get involved. In fact, in later experiments, they found that nucleosome assembly was 62% less effective when there was a set of 76 repeated CCG's. They suggest that this leaves the DNA vulnerable to a process called methylation, by which one of those C's basically gets an extra carbon molecule sticking off of it that can alter the way the DNA interacts with proteins later on and lead to gene silencing. The consensus is that methylation is probably the mechanism by which the FMR1 gene gets turned off. One thing I'm not clear on is that I had thought that the way that methylation leads to gene silencing was by recruiting an enzyme that helps lead to nucleosome assembly on that particular chunk of DNA. The DNA wrapped around nucleosomes is relatively unavailable for transcription and therefore the gene is switched off. But in this case the methylation is supposed to be in conjunction with a lack of nucleosomes. How does that work?Here are a couple really good websites from Fragile X research/education/fundraising organizations: Fragile X Research Foundation, National FragileX Foundation. References: Mandel JL, Biancalana V (2004). Fragile X mental retardation syndrome: from pathogenesis to diagnostic issues. Growth Horm IGF Res. 14: S158-S165. Neri G, Opitz JM (2000). Sixty years of X-linked mental retardation: a historical footnote. Am J Med Genet. 97: 228-233. Wen GY, Jenkins EC, Goldberg EM, Genovese M, Brown WT, Wisniewski HM (1999). Ultrastructure of the Fragile X chromosome: new observations on the fragile site. Am J Med Genet. 83: 331-333. Wang YH, Gellibolian R, Shimizu M, Wells RD, Griffith J (1996). Long CCG triplet repeat blocks exclude nucleosomes: a possible mechanism for the nature of fragile sites in chromosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 263: 511-516. |