|

Monday, October 30, 2006

A recent Perspective in Nature Reviews Neuroscience presents an alternative to the radial unit hypothesis of cortical expansion. As you may recall, one of the major alterations in gross brain structure as you move toward primates and those particular primates that we hold dear is the large increase in cortical surface area. The increase is not accompanied by a proportional increase in skull size because the increased amount of cortex is folded in on itself to form sulci (crevices) and gyri (hills). Smooth brains are called lyssencephalic. Wrinkly brains are gyrencephalic.

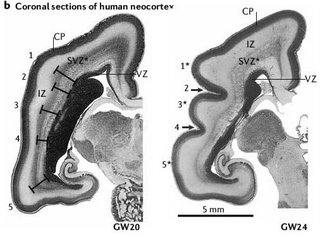

The radial unit hypothesis suggests that the increase in the size of the neocortex is due to an increase in the cells that both give birth to most cortical neurons and provide the scaffold for those newborn neurons to climb to their proper position in the cortex. These radial glia lie next to the ventricles (fluid filled cavities in the middle of your brain, one of the earliest neural structures to form) in an area called the ventricular zone (VZ) and are attached to the ventricles and to the outer surface of the developing cortex. Strangely enough, the area one layer further away from the ventricles is called the subventricular zone (SVZ). During cortical neurogenesis, neurons are created next to the radial glia and migrate up the scaffold. More cortex space can be created by producing more scaffolds. More scaffolds can be made by increasing the amount of time radial glia divide symmetrically to produce only more radial glia rather than neurons or reducing the number of radial glia that die after they are produced. A and B below.  But one potential issue with the radial unit hypothesis is that the ventricles should grow proportionally to the neocortical growth through evolution. This isn't the case. To circumvent this problem, the intermediate progenitor hypothesis suggests that the immediate product of asymmetric radial glia division is an intermediate progenitor rather than a neuron (C above). These intermediate progenitors migrate to the SVZ just above the radial glia and divide symmetrically some more to produce a crop of intermediate progenitors. Wherever you want more cortical neurons you let more intermediate progenitors be produced. Eventually these cells in a way that produces differentiated neurons and they migrate up to their proper position in the cortex. My favorite piece of evidence for this hypothesis is shown below. You can sort of predict where a cortical fold will be by measuring the thickness of the SVZ early in development. Thinner SVZs will be below sulci, and thicker ones will be below gyri.  Not knowing enough to really critique, my only obvious issue is that it doesn't seem like their criticism of the radial unit hypothesis has to be so. It seems possible to me for radial glia to proliferate without increasing the size of the ventricles that much. As far as I know, noone has shown that the ventricle surface is so jampacked with radial glia feet that it can't accomodate a few more. Also worth noting is that both hypotheses suggest that putting off neurogenesis to produce more progenitors might underlie cortical expansion in humans. So at this point, both hypotheses might lead to similar predictions about the particular genes involved. |