|

Thursday, December 21, 2006

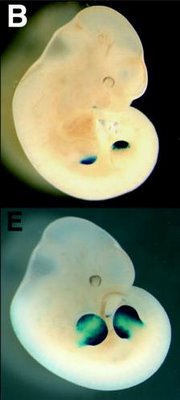

While we're on the subject of freaks, let's talk about polydactyly; that is, the presence of one or many additional digits on the hands and/or feet. It's actually a fairly common malformation, and it segregates as a dominant phenotype. But the genetic basis for this phenotype has only recently been elucidated, and the eventual culprit was a great example of an emerging pattern in human genetics. While we're on the subject of freaks, let's talk about polydactyly; that is, the presence of one or many additional digits on the hands and/or feet. It's actually a fairly common malformation, and it segregates as a dominant phenotype. But the genetic basis for this phenotype has only recently been elucidated, and the eventual culprit was a great example of an emerging pattern in human genetics. It all started with the mice--actually a polydactylous line of mice called Sasquatch. The reason for the name is a bit of a mystery to me, but in any case, Sasquatch had extra digits and showed misregulation of a developmental gene called Sonic Hedgehog. So perhaps these two event were linked--could the misregulation cause the phenotype? It's a good hypothesis. But the researchers are geneticists, so they had another question first: what is the genetic basis of the misregulation itself? This mouse line had been created by the insertion of DNA randomly into the genome, so perhaps the location of the insertion would give some clue as to how this misregulation was caused. The team then found the location of the inserted DNA, and saw that is was in the intron of another gene, over 1 million bases away from sonic hedgehog! So could this just be a fluke accident caused by the insertion of random DNA? That is, could polydactyly in humans really be caused by a mutation a million bases away from the gene involved? To determine that, you'd have to look at humans, and that's exactly what the next group of authors did. They found a highly evolutionarily conserved region a million bases away from sonic hedgehog and a number of families segregating polydactlyly with single base pair changes in precisely that region. That's striking, but it's still not enough to infer causality-- we're sticklers here, and that's just a correlation. There's one more experiment to do-- take the single base changes from the humans with polydactyly and see if they're enough to cause misregulation of a gene in the mouse. The results are what you see in the picture above-- the top picture is the normal copy of the sequence attatched to a gene encoding a blue dye, so you see blue dye everywhere the gene is expressed. In the bottom, you see the expression pattern of the gene attatched to the mutated sequence-- as you immediately notice, it's expressed all over the hand/paw. So there you have it-- a single base pair change a million bases away from a gene (in fact, in the intron of another gene) is enough to cause a dramatic phenotypic change like an extra finger. Crazy stuff. So what to take from this? A couple things: First, small regulatory changes can have big phenotypic effects. Second, determining causality of a regulatory mutation is a pain. Third, the elements that regulate the expression of a gene don't have to be near the gene-- indeed, this one was in the intron of the next gene over. So how important phenotypically are changes in the spatio-temporal expression patterns of genes? Potentially huge. |