|

Saturday, January 16, 2010

I've been interested in the transition toward agriculture, and its relationship to human health, for a while. There seem to have been two dominant paradigms in anthropology over the past century. The first is that agriculture spread because it was superior. Farmers were not as poor or ill-fed as hunter-gatherers. More recently, there has been a strong shift toward the view that on the whole the shift toward agriculture actually was associated with an increase in morbidity, and that hunter-gatherers lived lives of relative leisure. Though I lean toward the second view more than the first, it seems likely to me that the anthropological consensus, or at least the consensus communicated to the public, has shifted too far in the direction of the leisurely hunter-gatherer. No matter the exact case, I think it is important to look more at individual cases and the raw data, instead of resting on theoretical presuppositions. After all, it is possibly the case that in the pre-modern period the wealthiest populations of all would have been agriculturalists who existed in the short transient between the introduction of agriculture and the catch-up of the population to the Malthusian limit. It therefore makes absolute sense from a rational-actor model why hunter-gatherers might rapidly defect to the agricultural lifestyle in a world where mot arable land was unclaimed.

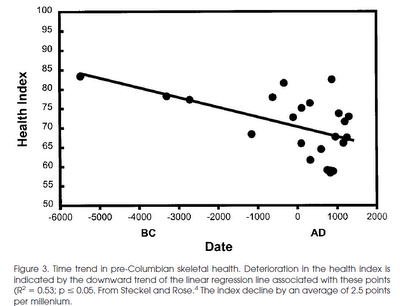

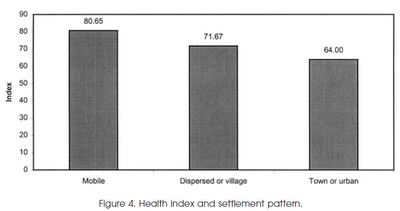

Poking around I found an interesting paper, Skeletal health in the Western Hemisphere from 4000 B.C. to the present (ungated version), which looks at health among native populations before the arrival of Europeans. The New World is probably a good target for case studies because even in 1492 it seems that across much of North and South America there was still a great deal of inter-penetration between agricultural and non-agricultural lifestyles, which some populations practicing both in a facultative manner. Here are the two most interesting figures:   There's a lot of variance, but the trendline seems clear. Additionally, the authors note that after 1492 the native skeletons are often more robust and indicate more health than before, despite the introduction of Eurasia pathogens. I think the reasons for this are two-fold. First, short-term mortality can result in a medium-term decline in morbidity, as the population drops far below the Malthusian limit. Second, the authors note that plains nomads are overrepresented in the post-1492 samples. These populations with horses had radically transformed their lifestyles, and were arguably much more affluent after the transference of the European toolkit, as they rode along the transient between two Malthusian limits. Labels: Agriculture, anthropology |