|

Saturday, January 16, 2010

I've been interested in the transition toward agriculture, and its relationship to human health, for a while. There seem to have been two dominant paradigms in anthropology over the past century. The first is that agriculture spread because it was superior. Farmers were not as poor or ill-fed as hunter-gatherers. More recently, there has been a strong shift toward the view that on the whole the shift toward agriculture actually was associated with an increase in morbidity, and that hunter-gatherers lived lives of relative leisure. Though I lean toward the second view more than the first, it seems likely to me that the anthropological consensus, or at least the consensus communicated to the public, has shifted too far in the direction of the leisurely hunter-gatherer. No matter the exact case, I think it is important to look more at individual cases and the raw data, instead of resting on theoretical presuppositions. After all, it is possibly the case that in the pre-modern period the wealthiest populations of all would have been agriculturalists who existed in the short transient between the introduction of agriculture and the catch-up of the population to the Malthusian limit. It therefore makes absolute sense from a rational-actor model why hunter-gatherers might rapidly defect to the agricultural lifestyle in a world where mot arable land was unclaimed.

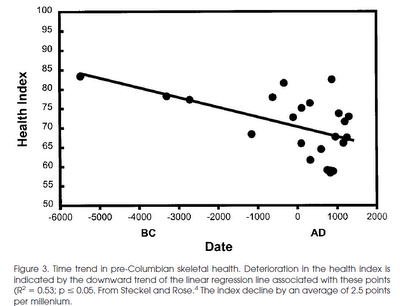

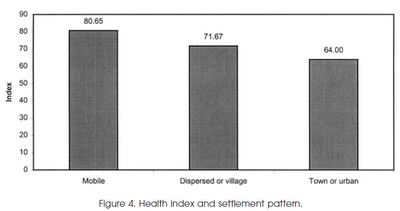

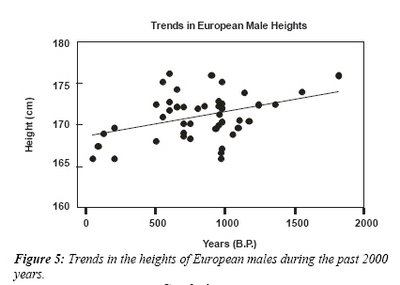

Poking around I found an interesting paper, Skeletal health in the Western Hemisphere from 4000 B.C. to the present (ungated version), which looks at health among native populations before the arrival of Europeans. The New World is probably a good target for case studies because even in 1492 it seems that across much of North and South America there was still a great deal of inter-penetration between agricultural and non-agricultural lifestyles, which some populations practicing both in a facultative manner. Here are the two most interesting figures:   There's a lot of variance, but the trendline seems clear. Additionally, the authors note that after 1492 the native skeletons are often more robust and indicate more health than before, despite the introduction of Eurasia pathogens. I think the reasons for this are two-fold. First, short-term mortality can result in a medium-term decline in morbidity, as the population drops far below the Malthusian limit. Second, the authors note that plains nomads are overrepresented in the post-1492 samples. These populations with horses had radically transformed their lifestyles, and were arguably much more affluent after the transference of the European toolkit, as they rode along the transient between two Malthusian limits. Labels: Agriculture, anthropology

Friday, November 13, 2009

How universal are human mate choices? Size doesn't matter when Hadza foragers are choosing a mate:

It has been argued that size matters on the human mate market: both stated preferences and mate choices have been found to be non-random with respect to height and weight. But how universal are these patterns? Most of the literature on human mating patterns is based on post-industrial societies. Much less is known about mating behaviour in more traditional societies. Here we investigate mate choice by analysing whether there is any evidence for non-random mating with respect to size and strength in a forager community, the Hadza of Tanzania. We test whether couples assort for height, weight, BMI, percent fat and grip strength. We test whether there is a male-taller norm. Finally, we test for an association between anthropometric variables and number of marriages. Our results show no evidence for assortative mating for height, weight, BMI or percent fat; no evidence for a male-taller norm; and no evidence that number of marriages is associated with our size variables. Hadza couples may assort positively for grip strength, but grip strength does not affect the number of marriages. Overall we conclude that, in contrast to post-industrial societies, mating appears to be random with respect to size in the Hadza. Here's some stuff from the discussion: Overall, however, our analysis suggests size and strength are not greatly important when Hadza are choosing a mate. This lack of size-related mating patterns might appear surprising, since size is usually assumed to be an indicator of health, productivity and overall quality. But health and productivity may be signalled in alternative ways in the Hadza, who are a small, relatively homogeneous population. An individual's health history may be more important than size, for example, and this may be relatively well known in a small, mobile population. Additionally, there may be some disadvantages to large size in food-limited societies, where the costs of maintaining large size during periods of food shortage may be high. Such disadvantages will not be seen in food abundant societies, so that large size may be a better indicator of quality in postindustrial populations. Finally, research on another African forager population found that height is negatively correlated with hunting returns (Lee 1979), suggesting that tall height may not be an indicator of productivity in such economies. Here's a chart which shows the proportion of females-taller-than-male marriages by culture:  In a previous post I suggested that the shift from small-scale societies to agricultural societies witnessed a transition from an emphasis on innate individual level social intelligence toward rules and heuristics (in other words, wisdom embodied in the preferences of society and its institutions). External physical characteristics are correlated with "health," so they're useful. And those who are not physically attractive can signal their own status and abilities in other ways, ugly fat men can for example buy material signalers to show that they have something going on. It strikes me that the Wisdom of Seinfeld is most appropriate for large urban areas with some degree of anonymity. Quick & dirty signalers to filter and influence one's choices are critical in the incredibly large number of human interactions possible in these urban agglomerations. By contrast, if George Costanza lived in a village one would know enough about his persona to dismiss a random "pairing" with an attractive woman as an aberration (or, one would know the back-story to this bizarre pairing). As our modern post-industrial society shifts toward information transparency perhaps we'll become less "shallow"? Remember the 1995 film Species, the attractive alien character met a handsome male at a night club. She assessed his fitness through his looks to make the initial choice. But later she killed him when she found that he was a diabetic. If she'd been able to access his health profile on her iPhone perhaps he would have been able to live for another day? Labels: anthropology, Evolutionary Psychology

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Dienekes points me to an interesting article, Ancient figurines were toys not mother goddess statues, say experts as 9,000-year-old artefacts are discovered:

Made by Neolithic farmers thousands of years before the creation of the pyramids or Stonehenge, they depict tiny cattle, crude sheep and flabby people. It's old joke that when archaeologists can't find a utilitarian slot to put an object, it becomes "sacred" or a religious object. The nature of the sacredness or religiosity of an object as it is perceived may tell us more about the culture in which the archaeologist lives than the ancient society itself (remember those peaceful Maya?). Labels: anthropology

Friday, October 17, 2008

From Barbarians to Angels: The Dark Ages Reconsidered:

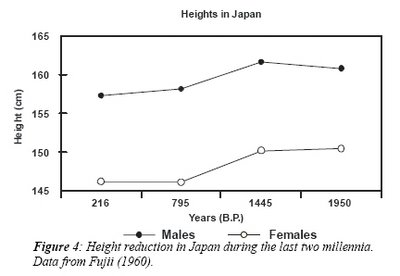

Measurements taken on skeletal remains in cemeteries in southwestern Germany indicate that the average height for men was about five feet eight inches, for women about five feet four inches, statures well above those of late medieval and early modern times. Measurements taken on skeletons in other regions are comparable. In Denmark, for example, the average height for men was about five feet nine inches-just above those for southwestern Germany-and for women about five feet four inches. These average heights were not achieved again until the twentieth century. Compared with earlier and later populations in the same regions, these average measurements show that most people had adequate nutrition during most of their lives and their living conditions were generally goodThis is in line with the charts I posted below. With the introduction of the three-field system, mouldboard plow and horse collar northwest Europe, in particular the regions of northern France, the Low Countries and the Rhineland, surpassed the Mediterranean as the population center of the continent (at least its western half). During the expansionary phase, i.e., 500-800, the span covered by Barbarians to Angels, the Malthusian pressures would have been relatively modest. The screws would have been tightened up to the medieval demographic peak before 1300. In any case, remember my focus on morbidity vs. mortality? It might be apropos in this case. The uncertainty and political instabilities due to the collapse of the Pax Romana could plausibly have increased mortality as peasants were exposed to the erratic depredations of barbarian warrior bands. But as depopulation occurred, in part because of withdrawal from the frontiers in places like Gaul (France) an western Germany of most farmers, those who opted to remain and take on the risks would be relieved of some Malthusian pressures. I think the chart of European heights does point to this as well, you can discern a slight upward trend after the Black Death due to a radical population reduction. I've reedited one of the charts for clarity:  As for Barbarians to Angels, the author doesn't really make me reconsider. I've talked about my skepticism of the idea of revisionism in regards to the decline of Rome. The author argues that technological advances occurred during the Dark Ages, and that many cities remained active nodes in trade networks. But the author's treatment is highly qualitative where he had concrete examples of how complex society persisted after the collapse of the Pax Romana, and he repeatedly scolds the readers to not judge Dark Age societies by modern standards which would tend to align more with the priorities of Roman civilization (e.g., reading, writing, arithmetic, public architecture, basically what we might term civilization). If the author wants to strip the term "civilization" of any normative biases brought to bear due to the prejudice of moderns, the argument is won, amassing a large collection of ornate weapons with which one might be buried is just as Cultured as writing letters to your friends laced with literary references. A good cup of mead is at the same level as a Falernian. Labels: anthropology, height, History

In the posts below I wanted to make clear my assumption that morbidity was likely more prevalent during the Neolithic than the Paleolithic. This does not mean of course that the Neolithic people were necessarily poorer than the Paleolithic peoples; Greg Cochran recently told me that people got healthier for obvious reasons during the Great Depression. I would not be surprised if the rate of mortality was somewhat higher than during the Paleolithic simply because the hunter-gatherer lifestyle had less buffering against disasters because trade and social networks were poorly developed so that environmental variation took a greater toll.

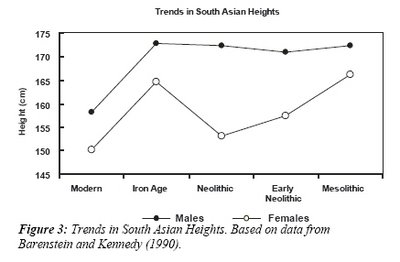

For me the biggest point to favor the idea of increased morbidity is that heights seem to have decreased after the Neolithic revolution. It seems plausible that nutritional shifts are the main reason that humans would shrink in size. Below the fold I have reproduced some charts from various papers for your reference.     The cite is Long Bone Dimensions as an Index of Socioeconomic Change in Ancient Asian Populations. Of course, height is not the only thing that changed. From Stature in Early Europeans: ...The sexual dimorphism creased in the more recent populations. Upper Palaeolithic humans not only were taller and had more robust bones in comaprison with the LInear Band Pottery Culture Neolithic people; they also had longer lims, a shorter trunk, and similar to modern African people, very long forearms and crural segments. The low brachial index is a very recently acquired characteristic of white Europeans. Agricultural populations as a whole have shifted toward a less robust physique. The increase in height due to better nutrition doesn't seem to have resulted in a more robusticity or a Palaeolithic dentition. So there may be some biological evolutionary parameters at work here as well. The first paper notes that between region differences in height seem to persist over long periods of time (East Asians are smaller). Phenomena such as Bergmann's rule point to changes in body form and size correlating with climatic shifts, and certainly the rise of agriculture is coincident with our current Interglacial. Labels: anthropology, height

Thursday, October 16, 2008

Sandy made another response to my assertions about HG's vs. farmers and quality of life, Agriculture Reduced The Periodicity & Amplitude Of Nutritional Stress. He's done a lot of research to support his specific contentions, and certainly everything he reports is generally true. But, I don't think it's necessarily relevant or representative of the issues at hand.

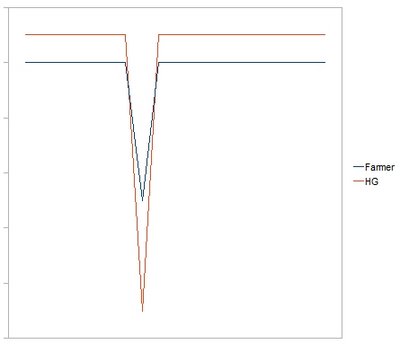

First, he says: I've done some reviewing of the literature and I still think that the probability that a child of an agriculturalist will reach reproductive maturity is higher than that of a hunter gatherer. Hell, that's why there's been a population boom ever since the Neolithic revolution. No, not necessarily. In a previous post he alludes to r vs. K strategies. Agriculture could simply be a r strategy. Children never born are not children ever had. So agriculturalists could have a higher growth rate by simply increasing the total number of infants produced over a reproductive lifetime. To make it explicit: Woman 1 = 6 live births and 3 survive to reproduce Women 2 = 12 live births and 4 survive to reproduce Obviously the second woman's offspring have a higher mortality rate before reproductive age, but that doesn't matter, there are more copies of her genes floating around. Population growth or decline is a dynamic which can be the outcome of many combinations of the parameters (e.g., fertility, mortality and generation time). If you know that in population A the mean number of children per woman is 3, and in B it is 4, you can not conclude that B has a higher population growth than A without knowing the death rates. Over the long term agriculturalists have had on average somewhat higher growth rates, otherwise hunter-gathering wouldn't have been totally marginalized as a way of life. But, that doesn't mean that populations grew very fast; the logic of compounding growth means that very small differences in average growth rates can result in great divergences over long periods of time. But, as I said in my previous post the issue isn't really about looking over the long term. When the Europeans arrived in North America and Australia they perceived the land to be "empty." Now, obviously there were peoples settled in these territories, but they're average density was simply far lower than was typical in Europe. Why? Because these peoples did not have the cultural toolkit to extract as many calories per unit out of land. Europeans, with their more productive agricultural toolkit could naturally support far larger populations than the natives from the same land because of culturally contingent factors. I think the same sort of dynamic can be projected back into the past. Imagine a group of agriculturalists who landed on the Breton coast 8,000 years ago, coming via sea from Portugal. The locals are hunter-gatherers who need enormous areas of range territory to support a small population. A group of farmers might be able to win or negotiate a "small" tract of land from the natives to farm. The natives might see this concession as minor; after all, they might not comprehend that a "small" territory from the perspective of farmers is actually going to be a "large" plot when conditioned on the agricultural techniques farmers had. During the early years farmers would experience plentitude as there is a surplus of land. Soon though they would need to expand, and here their ability to organize and project force because of their numbers would come to the fore. Not only would they be able to push back the hunter-gatherers, but likely powerful infectious diseases would sweep in front of their demographic wave. Soon, the only hope that hunter-gatherer tribes would have of defending against this would be take up farming themselves and become sedentarists. As this occurred the remaining hunter-gatherers would be pushed into marginal and less desirable land, further making the lifestyle relatively less attractive (any quality of life advantaged would be swamped out). There are plenty of data points which support these points from the last 500 years, from the European settlement of North America down to the relationship between hunter-gatherers and farmers in Botswana. Most of the rest of Sandy's post is an analysis of correct, but irrelevant or unrepresentative data. Or at least I think it is irrelevant, and suspect it is unrepresentative. To a great extent much of the human race today lives outside of the Malthusian trap, and the conditions of the past do not necessarily apply to today. Additionally, though over the long term populations grew rather slowly in the pre-modern era, there were local fluctuations up and & down. We know this for a fact from cultures where we have demographic data (e.g., England and China), so a "snapshot" of a given period does not allow us to generalize well across time. Comparing contemporary hunter-gatherers today with contemporary agriculturists is probably not representative of past conditions. For me the biggest problem is that hunter-gatherers today are selection biased toward regions where agriculture is not at much of a comparative advantage. This is why I tend to be more interested in comparisons of remains within a particular region which went through the lifestyle transition in the past. My general impression is gross physiological health declined. In other words, farmers are, on average, subject to greater morbidity, even if hunter-gatherers have more mortality. In any case, one of the problem here is bigger meta-issue in the debate between Sandman and myself: Anyways, in my previous post I outlined some of the ethnographic reasons why I think so. In this post, I'll share some of the demographic data that supports my hypothesis. I know less cultural anthropology than he does, and I'm not interested getting to know the whole literature. I could go to google scholar and look up some research articles which support my view because there are a lot of articles out there, and I'm sure I could find some trash which would support any contention I make. That's why I'm leaning back on the theory about Malthusian assumptions that I can be rather certain of, even if I'm wrong as an empirical matter I can argue the logic with some concreteness and consistency. I'm not convinced by Sandman for all the reasons above, but, at the end of the day I wouldn't be convinced by a few surveys of the literature because I'm sure I could selectively troll through the literature and find authorities to support me too. If I actually knew the literature with any fluency I could ascertain the value of any given citation I dig up, but since I don't know the literature I'm really concerned about just selection biasing what I get based on the way I formulate a google scholar query. This is also why I'm pretty down on the citation wars which occasionally crop up in the comments, I strongly have the suspicion that the interlocutors aren't really digging into each other's citations, but rather just going to search for more papers to support their own argument. What's really the point of all that? So I have decided to ask some people who really are in the "know" (that is, anthropologists who aren't CAFRs) what they think. Oh, and also: Razib equates hunter-gatherers to lions, and farmers to antelopes. Lion cub mortality rates are higher than antelopes, upwards of 80% of cubs do not make it to adulthood. Whereas antelope calves, if they survive predation, have much more greater chances at seeing sexual maturity. It is much more precarious to count on mom to provide milk and hunt at the same time, than it is to graze. So, this issue is less about absolute availability and more about reducing the periodicity and amplitude of nutritional stress. And this is one of the reasons why the agricultural diet has 'won' over many humans, even despite the many shortcomings it has. To the first approximation I somewhat accept this, but I'm not totally sure, and the characterization might elide some of the details. Imagine a scenario like the chart below, where Y = nutritional quality and X = generation. The average for a hunter-gatherers might be higher, but the far higher "floor" of farmers might make all the demographic difference over the long term.  Addendum: I don't know cultural anthropology well, aside from the fact that CAFRism is endemic, but I do know something like the society of the Roman late antique period relatively well for a lay person, so I have seen people make arguments based on obviously retarded citations. Now, since these people are frankly retarded, dishonest or ignorant (or any combination thereof) any well informed response is really totally futile; people who can't evaluate the plausibility of their own argument based on the quality of the authorities which they cite aren't going to be able to evaluate the plausibility of someone else's authority. This explains why I'm responding to Sandman in broad theoretical generalities and methodological objections; if I "dug in" by spending time looking for literature support my case I'd turn this into a lawerly dialogue, and what's the point of that? Granted, I know Sandman better than if he was just a "random" from the internet, but still, life is short. Labels: anthropology

Sandy has a post up, Why Do Women Have More Cavities?, where he reviews the John Lukacs paper I pointed to yesterday. He says:

So ultimately female physiology combined with the the changes in diet and increased feritlity are the reasons why women have more cavities than men. Razib mentions that with increased fertility comes a reciprocal increase infant mortality, especially because the agricultural revolution increased communicable diseases. He concludes that hunter-gatherer infants are far more likely to reach reproductive age than infants of an agriculturalist. I mentioned in the comments that I'm pretty sure that he misunderstood me. So I'll clarify my conception in this post. Unfortunately, though I'm obviously interested in this particular topic (you know this if you read the blog) I'm not that familiar with the cultural anthropological literature, so all my assertions are very provisional because I don't feel confident I know the literature well. Nevertheless, in regards to my basic logic I'm confident that if Lukacs and others are right in regards to birthrate, what I said has to be true. Here is what I said: ... In contrast, hunter-gatherer women typically have a reduced number of pregnancies because of behaviors such as extended breastfeeding. Of course, most agricultural societies quickly reached the Malthusian limit (ecological carrying capacity), so the higher fertility was likely balanced out by higher infant mortality. If agricultural women gave birth to more infants a greater proportion of these offspring ended up dying of diseases, etc., than for hunter-gatherers. So at birth any given hunter-gatherer infant is far more likely to reach reproductive age than any given offspring of peasants.... I was careful with the words I used here. I was working with a Malthusian assumption in regards to pre-modern populations. In short, most of the time populations did not exhibit the sort of long term sustained growth rates of the last few centuries. In medieval England, where we have some documentary demographic sources, we know that the population crashed during the Black Death and didn't reach its pre-crash peak for over two centuries. I recount this to make clear I do understand that the flat population growth curves you see for pre-modern demographics are generally "smoothed" and there were wild local fluctuations. But, these fluctuations oscillated around an "ecological carrying capacity." There is of course another dynamic which occurs some of the time. If, for example, a human population discovers new territory where there is a surplus of land and Malthusian pressures are minimal, you will see a transient logistic growth curve. That is, population will increase up the Malthusian limit, what biologists would term the "carrying capacity." The United States during the period between 1650-1850 is a really good case for this. The number of white Americans rose because of immigration, yes, but there was a very high endogenous rate of growth driven by natural increase. In Albion's Seed David Hacket Fisher reports that in New England there were many towns where the average number of live births in a woman's reproductive span was north of 10! This is of course feasible when you have such a asymmetry between land, resources from which humans can derive sustenance, an the number of humans. Not only were New England families fertile, but European observers such as John Crevecoeur commented upon the relative physiological health of Americans during this period compared to those of the British Isles or the Continent (large, plump, vigorous). When you are below the Malthusian limit there is far less constraint on resources and so individuals are at their nutritional optimum. Carrying capacity does vary as a function of ecology and culture. There is a reason that Yangtze delta was more densely populated than European Russia in 1700; not only is rice more efficient at producing calories from any unit of land in comparison barely, wheat or oats, but the climate in that region of China allows multiple croppings over the year. These sorts of ecological parameters are common sense. But though the population density might differ by around an order of magnitude, Russian and Chinese peasants had a similar quality of life (though there is differences on the margins, they are not predicted by the difference in density). This is because both populations were pushing up against the Malthusian limit, or carrying capacity, of their locality. When you compare agriculturalists to hunter-gatherers, you will likely know that the former live at higher densities than the latter. You will also know the former to be far more sedentary than the latter. This is not strictly a function of ecology; almost all regions where agriculture came to dominate were once inhabited by hunter-gatherers. In fact, there is plenty of evidence that many of the latter switched lifestyles to become farmers. Sometimes the process could take some time, for example there is a fair amount of archaeological evidence in southern Sweden that non-agricultural societies had a flourishing trade with agriculturalists for thousands of years. Why so long for the switch? The crops of the Middle East emerged in the Middle East, and so the cultural toolkit took some time to evolve so that it was attractive and preferable to northerners. Why did hunter-gatherers become farmers? One can posit many reasons. But remember what I said about the logistic growth along the transient? This can take some time. We in the United States don't really know how long it would have taken America to "fill up" so that the European misery index was recapitulated among Yankee yeoman (the frontier did not close until almost 1900). The demographic transition in the late 19th century changed the whole game. If you are a hunter-gatherer, and you see that your neighbor can extract many more calories out of a smaller amount of land and so have a larger family, it might seem like a rather rational choice. If thinly scattered hunter-gatherers switched to agriculture they would slide along the transient of the logistic growth curve for many generations. In fact, the early adopters would never know of the misery which later generations would take for granted! The cultural invention of agriculture changes the whole game, at least temporarily. But eventually the law of diminishing returns kicks in, an the balance between land and population returns. The stationary state has been achieved. And it is because of the stationary state that I said what I said about fewer offspring reaching reproductive age. If a population is stable then parents only replace themselves. This is true whether one is a hunter-gatherer or a farmer. But, what about Lukacs' assertion that females in agricultural societies had a higher birth rate? Well, naturally then there must have been a higher mortality rate. That is why I referred to pregnancies; if hunter-gatherer women space their births through weaning an abstinence then they might have had many fewer pregnancies than the wives of farmers. But if both populations were at the Malthusian limit the surplus must be "pruned" by mortality, and more surplus implies greater mortality. Why did hunter-gatherer women wish to space their births? The general hypothesis is that mobile groups need to maintain a reasonable ratio of productive adults to very young children. A hunter-gatherer woman would have had a more difficult time of managing multiple toddlers because of the need to move them on occasion. In contrast, a woman living in a village might be able to manage with multiple toddlers. Additionally, once the children reached the age of 5 or 6 they might have been economically valuable producers. If many of them died of disease before they reached the age of reproduction then the society could gain their production without having to worry about them contributing to higher population growth or taking care of them in their dotage. As for all the stuff about how miserable hunter-gatherers were, that's pretty much irrelevant without a reference point to the misery of farmers. As I said, I don't know the literature very well. A Malthusian model should predict basically the same wealth for hunter-gatherers an farmers over the long term. That's close to what Greg Clark in Farewell to Alms assumes, though there are qualitative differences in the way farmers consume and hunter-gatherers consume. Life is not a continuous trait, you're alive, or your'e not. Farmers tend to have much less diverse diets than hunter-gatherers for rather obvious reasons. Because of the density of villages an the emergence of higher order social structures which foster more trade and commerce farmers are subject to more powerful epidemics. It seems though that hunter-gatherers often live violent lives, and without economies of scale and recourse to mass social collective action they might be more vulnerable to various types of environmental perturbations over the short term. In other words, these two pre-modern groups both lived like crap compared to today, but somewhat differently. From all I have read if called on to give the quality of life award to either lifestyle anthropologists would today seem to tap the hunter-gatherers as being on top. It isn't just about dental carries. Farmers are physically smaller and exhibit more evidence of chronic nutritional stress than hunter-gatherers (that is, comparing remains from a locality which made the transition across a span). As noted in some of the papers below the higher fertility of farmers was almost certainly balanced by a higher mortality; a conscious human at the age of 5 seems to have had a greater likelihood of dying early among farmers because there were just more of them floating around. Here are some papers to support the above claims (more or less): The origins of agriculture: Population growth during a period of declining health Biological Changes in Human Populations with Agriculture Testing the Hypothesis of a Worldwide Neolithic Demographic Transition Agents Adopting Agriculture:Modeling the Agricultural Transition If you're a cultural anthropologist who knows more about this please add citations and results in the comments, I'm curious but I don't have the time to really familiarize myself with the literature to make strong judgments. Don't be a CAFR and ramble on about something you don't know about or spend 12 paragraphs on problematizing the word "farmer." Note: The title: I sometimes think of hunter-gatherers as lion and farmers as antelope. There are many more of the latter because there's a lot more grass than antelope. Additionally, if a lion gets injured there's no way they're going to catch an antelope, it's a high risk profession. But who would you rather be? Note that the European aristocracy generally hunted as opposed to gardened. See Tim Blanning's The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe: 1648-1815. Addendum: Unfortunately, this isn't for pre-modern populations necessarily, but I thought readers would find this chart of interest....  Labels: anthropology

Tuesday, September 09, 2008

Steve points me to a John Tierney column, As Barriers Disappear, Some Gender Gaps Widen:

"Humanity's jaunt into monotheism, agriculturally based economies and the monopolization of power and resources by a few men was 'unnatural' in many ways," Dr. Schmitt says, alluding to evidence that hunter-gatherers were relatively egalitarian. "In some ways modern progressive cultures are returning us psychologically to our hunter-gatherer roots," he argues. "That means high sociopolitical gender equality over all, but with men and women expressing predisposed interests in different domains. Removing the stresses of traditional agricultural societies could allow men's, and to a lesser extent women's, more 'natural' personality traits to emerge." I've made this precise argument on this weblog for several years now. The preoccupation with self-actualization and personal fulfillment which is the true religion of the mass consumer society is not something that I think is historically contingent or a random act of cultural evolution. It is an expression of a very deep rooted modal psychological predisposition that has echoed down from the Paleolithic and has simply been evoked by the modern context. With all the talk about recent human evolution and the effect of agriculture obviously we've deemphasized the whole Pleistocene Mind model which was in the vogue with Evolutionary Psychologists. But these sorts of distinctions of emphasis highlight that variations of truth are often quantitative, not qualitative. Reality is a mix of various elements, not a set of stark alternatives. Agricultural peoples may carry more copies of AMY1, but they still enjoy the taste of meat. And it is illustrative that the elites of many agricultural societies allocated much of their marginal time to the sport of hunting. After The Great Divergence and the transition to mass wealth societies we saw unleashed these ancient pent up preferences on a broader level. Today hunting is no longer the purview of rentier aristocracies who engage in their pleasures by capturing the surplus production of the peasantry. But we have not gone back to the past in some Eternal Recurrence. Rather, elements of pre-Neolithic psychology that have come to the fore and become explicit aspects of our cultural framework remain embedded in a matrix riddled with the great residual institutions of the traditional post-Neolithic world (e.g., religion, monarchies, formal law, etc.). And of course though we live in a culture where individuality is prized, we are not fragmented into small hunter-gatherer brands. Instead, the post-Industrial society dwarfs the post-Neolithic in the potential scope of social networks and scale of our tribes to such an extent that even the aforementioned institutions which arose to grapple with the complexities of the pan-tribal world have been stretched to their breaking points. Labels: anthropology, culture

Tuesday, August 05, 2008

Tyler points me to a new paper coming out in PNAS, Male dominance rarely skews the frequency distribution of Y chromosome haplotypes in human populations. It isn't on the site yet, but New Scientist has a write up:

To determine whether dominance could last more than a couple generations, Watkins and a team of anthropologists and geneticists sifted through the DNA of 1269 males from 41 Indonesian communities. How does Wilkins know this about Mongolians? Perhaps there's some empirical data in the paper he isn't reporting re: Mongolia, but it seems that one must be cautious about extrapolating from Indonesia. As most of you know, Indonesia is an archipelago, and water tends to be really good at bottling up gene flow. Of course, this is a big question that spans all human societies across time. I assume there are going to be variations across space, and time, and that frequency dependence is important as a conditional which frames any assertions we make. I suspect that Genghiside "super-male" lineages are more a feature of the last 10,000 years where it is possible for only a few people to sequester large amounts of surplus productivity and travel was much more common along elites. Additionally, I've made this point before, but I'll do so again: in many pre-modern societies being a high status male opens you up to a great deal of risk and gain simultaneously. So there might be a long term angle in turning your vehicles into indispensable betas.... Labels: anthropology

Monday, June 02, 2008

Selection speculation: CLOCK and reward-dependence in Africans

posted by

agnostic @ 6/02/2008 02:39:00 AM

Since so many comments lead off with some variant of "I would guess," why not try to corrall them all into one post where they could serve a purpose? Each week I'll find some area of the human genome that shows signs of recent selection, see what phenotypes the gene affects, and although I'll likely provide the most convincing story, readers can conjecture to their heart's content about what might have driven selection. It may, for once, improve the discussion to comment while still deranged from last night's drink.

Let's start with the data: using Haplotter, we see that for the gene CLOCK, there is a signal of recent selection in Africans but not in Europeans or Asians. The CLOCK gene is involved in maintaining our circadian rhythm, and I started this search looking for between-group differences in being "day people" vs. "night people." However, other genes related to circadian rhythm -- PER1, PER2, PER3, Tim, CSNK1E, Cry1, and Cry2 -- show no signals of recent selection anywhere. So perhaps there is something else that CLOCK does that these others do not. It turns out that CLOCK is also involved in the dopaminergic system, which regulates mood and behavior. None of the OMIM entries for the other circadian rhythm genes mentions dopamine, mood, the reward system, etc. So it is more likely that CLOCK has undergone selection for its effects on mood and on the brain's reward system, rather than on circadian rhythm per se. In mice, and so potentially in humans as well, mutations in CLOCK make individuals lower in anxiety and higher in risk-taking (Roybal et al. 2007; free full text). Turning to data from Lynn & Martin (1995), which I turned into a convenient graph here, we see that Nigerians -- the African group that HapMap data come from -- are indeed the lowest in the world in the personality trait Neuroticism (the Israeli data-point must be a mis-coding by Lynn, who is known for doing so). They are also the highest in the world in Extraversion. Neuroticism measures a tendency toward anxiety and related states, while Extraversion measures, among other things, pace of living (manics living a faster-paced life) and excitement-seeking. So Nigerians show a psychological and behavioral phenotype that's fairly comparable to the mice with mutations in CLOCK, strengthening the hypothesis that selection at CLOCK has acted on personality rather than circadian rhythm per se. Now comes the fun part -- telling a story about why this phenotype was more advantageous in Western Africa than in Central Europe or Northeast Asia over the past 10,000 or so years. The low-anxiety and high-excitement-seeking phenotype is suspiciously like that associated with derived alleles at the DRD4 locus, and the novelty-seeking 7R allele at that locus does show up at intermediate frequencies in Africans (Chen et al. 1999; see a map here). I concur with Harpending & Cochran (2002) (free full text), who argued in the DRD4 case that the phenotype is more advantageous in "cad societies" than in "dad societies." More concretely, I suggest, based on the teachings of the pickup artist community, that low anxiety aids in approaching more females in a shorter time -- you are less paralyzed during the approach, and you get over rejection more easily -- and that higher risk-taking motivates you to approach more females. Contingent upon having other traits that are appealing to females (a muscular body, artistic skill, dancing or singing ability, a knack for flirting, and so on), the phenotype here would have increased male success in courtship of (multiple) females, a stronger determinant of reproductive success in a "cad society" than in a "dad society." Lastly, here are two testable predictions: 1) lowland South American and highland New Guinean tribes should also show signs of selection at the CLOCK locus, since they are even more prototypically "cad societies," and they have the highest frequencies of the 7R allele at DRD4. And 2) African Bushmen should show no signs of selection at CLOCK since they are more "dad societies" and have lower frequencies of the 7R allele at DRD4. (ALFRED does not have data on CLOCK.) The fact that Northeast Asians do not show signs of selection at CLOCK already supports the hypothesis, since they are more "dad societies" and have a very low frequency of 7R at DRD4 (and even the 2R allele, which shows up somewhat there, has a much more muted effect than does 7R). The lack of selection at CLOCK in Central Europeans is neither here nor there: they are more "dad societies" than Western Africa but not so much as East Asia; Europeans also have intermediate frequencies of 7R and DRD4. So we could have an example of "Rushton's Rule," where East Asians show no selection for low-anxiety / high-novelty-seeking alleles at either DRD4 or CLOCK, Europeans show selection at just one locus, and West Africans show selection at both. To the best of my knowledge, as they say, this is the first argument for why Africans show a signal of selection at CLOCK. Consider it part of the graduate student with a PC trend in studying human evolution. You heard it here first. References Chen, C., M. Burton, E. Greenberger, & J. Dmitrieva (1999). Population migration and the variation of Dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) allele frequencies around the globe. Evolution and Human Behavior, 20(5): 309-324. Harpending, H. & G. Cochran (2002). In our genes. PNAS, 99(1): 10-12. Lynn, R., & T. Martin (1995). National differences for thirty-seven nations in extraversion, neuroticism, psychoticism and economic, demographic and other correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(3): 403-406. Roybal, K., D. Theobold, A. Graham, J.A. DiNieri, S.J. Russo, V. Krishnan, S. Chakravarty, J. Peevey, N. Oehrlein, S. Birnbaum, M.H. Vitaterna, P. Orsulak, J.S. Takahashi, E.J. Nestler, W.A. Carlezon, Jr., & C.A. McClung (2007). Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. PNAS, 104(15): 6406-11. Labels: anthropology, babes and hunks, Genetics, human biodiversity, Human Evolution, Personality, speculation

Tuesday, January 01, 2008

First, happy New Year! Second, when I saw this post from Matt in the referrals I assumed he was going to be offering some skepticism as to the utility of formal models in science. No, not really, not that type of model. The sort that our resident callipygiaphile ruminates upon.

Labels: anthropology

Sunday, December 30, 2007

Since the previous post was about the tendency toward radical skepticism and subjectivism within cultural anthropology, I thought I would point to this piece in The Economist which highlights positive insights from various anthropological fields. The article emphasizes the possible role that population pressure and the quest for food might have had in spurring human innovation, from the atlatl to agriculture. An interesting point to note is the implicit suggestion that high rates of hunter-gatherer warfare might have constrained population pressure and possibly lead to relatively higher standards of living; something familiar from Greg Clark's model. From a population genetic angle, I am curious as to whether the endemic warfare of cultures which were pre-state resulted in higher or lower Nm*?

* N = population, m = migration rate. Nm > 1 results in equilibration of allele frequencies across demes, while Nm < 1 tends to lead to divergence. Labels: anthropology

Tuesday, October 02, 2007

When genetics is used as a supplement to history or anthropology it should ideally offer more precision and reduce the field of possibilities. Unfortunately that is not always the case. For example, when asking big questions such as "Are humans 'naturally' patrilocal?" genetics has generally come up with conflicting results. The fact is that about 70% of "traditional" societies are patrilocal; wives move to live with husbands and their family. Some genetic evidence seems to support this (e.g., greater mtDNA [female] variation than Y [male] lineage variation), but there is also variation within populations and some skepticism as to whether such simple comparisons between different uniparental loci really can give a definitive answer.

This paper in PLOS ONE tackles the question using comparisons with chimpazees to help calibrate our expectations, The Genetic Signature of Sex-Biased Migration in Patrilocal Chimpanzees and Humans: ...Here we review some methodological reasons for these inconsistencies, and take them into account to provide an unbiased characterization of mtDNA and NRY variation in chimpanzees, one of the few mammalian taxa where males routinely remain in and females typically disperse from their natal groups. We show that patterns of mtDNA and NRY variation are more strongly contrasting in patrilocal chimpanzees compared with patrilocal human societies. The chimpanzee data we present here thus provide a valuable comparative benchmark of the patterns of mtDNA and NRY variation to be expected in a society with extremely female-biased dispersal. Homo Sapiens, are a complex species. We're capable of a lot and our level ofsocial complexity isn't truly cognitively tractable for the mental toolkit that evolution has given us. So we make recourse to generalizations and first-order approximations. The problem with this is that sometimes the deviation away from the central tendency is as interesting and evolutionarily salient as the mode on the frequency distribution of the trait. When we say that 70% of human societies are patrilocal, that means that 30% are not. That also doesn't mean that 70% of human societies have always been patrilocal. It also doesn't quantify how much deviation there is from social expectation, e.g., perahps in the 70% of societies which are patrilocal a substantial minority of males move to the locality of the female, or, males and females from the same locality marry each other so that the whole dichotomy is rendered irrelevant (though even if you live within a village whether you reside in the relatives of the female or relatives of the male in an extended family circumstance is also an important point). Generalizing about the modal behavior of our species may leave the concept more analytically tractable, but it may also render our model inaccurate toward the point of uselessness. On the other hand, chimpanzees aren't that complex...at least compared to humans. Yes, I know that chimps are the geniuses of the animal kingdom, but the chimp is the Peter Keating of the animal world and we are the Howard Roarks. Unlike humans with their facultative complexity chimpanzee societies are pretty uniform. While there are exceptions to the rule (as in the famous Gombe troop), female chimps tend to leave their natal group while males tend to remain in their natal group. In shot, chimps seem to be much more obligate in their patrilocality than humans. The workers above note that both chimp lineages, the bonobo and common chimp, are patrilocal, so this is likely an ancestral characteristic of the clade dating back at least 1 million years. It seems that chimpanzees exhibit a much more unambiguous genetic signature of patrilocality than humans, the ratio of Y to mtDNA variance is significantly lower than in humans. There are some technical reasons why the human results could exhibit problems. For example, mtDNA might simply be more diverse than Y lineages for endogenous reasons (higher mutational rates?). Or there might be lower effective population size of one sex, which would skew the variation of the uniparental lineages independent of deme-to-deme gene flow. There are also issues of coarseness of analysis, the authors point out that in some human communities Fst analyses were preformed by spanning tribal groups where intermarriage was rather uncommon, while ignoring the pervasiveness of between deme gene flow on the intra-tribe level. Finally, there is the issue that human societies change. The Japanese were once matrilocal, but now the are patrilocal. Within historic times many matrilineal societies have shifted toward patrilocal practices (though sometimes there are ghosts of matrilineal practice, in ancient Egypt marriage to a woman of the royal line was often essential to solidify the claims of the male claimant). There variations over time can obscure or erase genetic patterns and replace them with new ones, and periodic oscillations would presumably result in a meta-stable level of diversity which balances out both mtDNA and Y. Chimps can get around some of these issues. Chimpanzee societies are more homogeneous in their behavior patterns, have been studied for nearly two centuries, and have been characterized to a very fine level of demic structure in terms of their social dynamics (even to the point of familial histories). In short, chimpanzees are empirically tractable because of their small numbers and limited set of behaviors. The similarity across the two clades and their relative homogeneity should reassure one that temporal variation is minimized. Because of their charismatic nature chimpanzees have also been tracked in a way which makes assessments of male vs. female migration patterns on the level of specific demes tenable (i.e., you couldn't get funding to do such detailed research on most species, so people have to engage in a lot more guesswork in terms of how they behave when no one is looking, which can explain why ethologists were long fooled by "monogamous" birds before DNA fingerprinting cleared up some issues). It seems only the most extremely patrilocal and polygynous human societies in the sample approached the chimp norm. To me this suggests that we'll have to be a bit more careful and qualified when talking about human patrilocality. Though we're not totally malleable and subject to great constraints, our behavioral flexibility is orders of magnitude more developed than the faculties of our chimp cousins. It shouldn't surprise if we tend to explore a far greater sample space of social systems, not only because we can, but also because we inhabit so many environmental and cultural ecosystems. Polyandry which consists of brothers marrying one woman in Tibet did not arise because it was natural; rather, it seems to be the best opportunity for reproduction that a low status male could attain in that society where resources were at a premium. It was a functional response to a specific set of circumstances. This work focuses on the dimension of male and female migration across adjacent demes, classical models of gene flow. And this likely works well for chimpanzees, and perhaps hunter-gatherers. But it seems excessively oversimplified when it comes to the mass societies which arose after the rise of agriculture. 4,000 years ago a man who was born in Switzerland was buried at Stonehenge. In their day the Mongol hordes swept from the Pacific to the plains of Pannonia, from Baikal to Baghdad. This was certainly a scattering of Y lineages of immense scale. These sorts of movements don't really work well with chimpanzee analogs...because, well, chimps have never produced transcontinental hordes! Atop the simmering activity of deme-to-deme wife and husband exchanges there will periodically flash a fire of migratory activity. Sometimes this will be a total folk movement, but I suspect that more often what you would see was a migration of males. There is much more variation in human social networks than among chimpanzees, so we should focus less on the mean outcome as opposed to the structure and pattern of the variation and its distribution. Note: You can discuss this paper over at PLOS ONE if you so choose! Langergraber KE, Siedel H, Mitani JC, Wrangham RW, Reynolds V, et al. (2007) The Genetic Signature of Sex-Biased Migration in Patrilocal Chimpanzees and Humans. PLoS ONE 2(10): e973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000973 Related: Sperm competition. Labels: anthropology

Thursday, September 13, 2007

Four Stone Hearth, the anthropology blog carnival, is over at John Hawks' place.

Labels: anthropology

Friday, May 11, 2007

Here is a story about a museum which returned Tasmanian Aboriginal remains to a community group without doing DNA analysis, because they argued that this sort of compromise would preserve them for future analysis. This is a tricky area. I'm obviously generally disinclined to sympathize with "communities" who claim bones because the individuals making the decisions are simply individuals, and often individuals playing politics. That being said, the history of the Tasmanian Aboriginals was characterized by proactive bestial treatment on the part of Europeans, and the relationship of the native peoples of Australasia and "civilization" has been highly "problematic." I think that from a cost vs. benefit standpoint targeting descendants of Aboriginal groups is perhaps a better bet, community groups can't make a strong argument that they have a right to decide whether someone gives genetic material or not. I'd honestly be curious to hear what John Hawks thinks, seeing as he's an anthropologist and so has presumably thought this issue through to some extent.

Labels: anthropology

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

Since we're talking about chimps, check out this long story about the species which surveys the opinions and research of a range of primatologists.

Labels: anthropology

Saturday, April 07, 2007

That seems to be the conclusion of a recent review of Nick Wade's Before the Dawn published in Nature Genetics:

My reluctance to recommend the book stems also from Wade's discussions of 'race' and biology. I agree with Wade that there is something biological about racial categories. In my opinion, although racial identity is socially negotiated, people use physical traits as cues when 'assigning' a racial identity to themselves or another individual. Racial categorization isn't blind to biology. ... Although one might detect biological differences between races, any highlighting of the racial categories (just a subset of groups with biological correlates) has social costs, according to recent social science research. On the other hand, Neil Risch, cited often in the book, has argued that there are significant (medical) costs of ignoring the relationship between racial categories and biology. I suggest that these different costs be weighed in each circumstance where one might link 'race' and genetics. Wade's broad description of races as clearly delineated biological entities is unjustified in the context of a book about human history intended for a general audience. Why use the term 'race', when 'geographic ancestry' or 'continental origin' are more accurate and less costly in social terms, especially since Wade's definition of 'race' is "continent of origin"? I suggest acknowledging the correlation between racial labels and continents of origin, and saving the term 'race' for contexts in which social costs are outweighed by other costs. This is not the argument I expected to follow the sentence "My reluctance to recommend the book stems also from Wade's discussions of 'race' and biology." In this case, the author isn't being snide by putting race in quotes, as she really means the word race rather than its referent. How often do scholars write that consternation over race is largely related to extra-scientific concerns? However, I have to criticize this argument, at least to the extent that I'm able to examine the evidence presented. A footnote to the "recent social science research" showing that using the word 'race' is harmful (but that cryptic synonyms are OK) would be appreciated, as this forms the basis of the argument against discussing 'race'. Is it only harmful to discuss 'race' and 'genetics' or 'biology'? Is the attribution of racial differences to environmental/cultural causes not similarly harmful? Is it really true, as is implied, that Wade is morally obliged to substitute most instances of "race" in his text with "continent of origin"? There's a lot to commend in this review, largely stemming from the reviewers' honesty and directness, and especially in contrast with this hatchet job published in the sister journal Nature. Update - full text: Given the rich content of Nicholas Wade's latest book, Before the Dawn, I wish I could simply recommend the book, describe its highlights and stop there. Wade provides a valuable overview of the last ten years of scientific literature on genetic insights into the history of our species. He is an excellent storyteller, weaving the scientific results into a thrilling tale of human migration and settlement, competition and warfare, cultural and linguistic evolution and environmental challenges. The history of our species is a fascinating one, and Wade brings it to life. Labels: anthropology, Books, Genetics, race |