|

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Updated

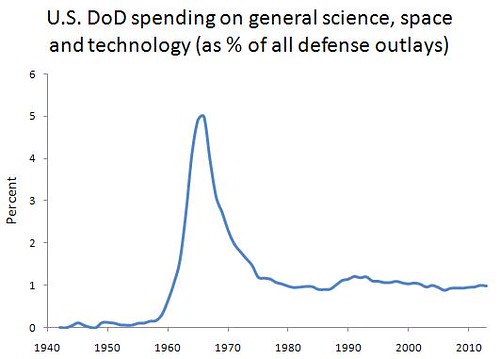

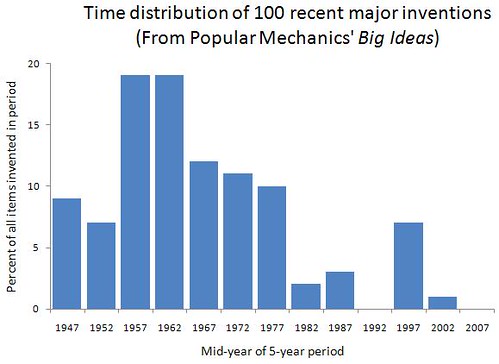

This may be old hat for some readers, but it's worth reviewing and providing some good new data for. The motivation is the idea that monopoly-haters have that when some company comes to dominate the market, they will have no incentive to change things -- after all, they've already captured most of the audience. The response is that industries where invention is part of the companies' raison d'etre attract dynamic people, including the executives. And such people do not rest on their laurels once they're free from competition -- on the contrary, they exclaim, "FINALLY, we can breathe free and get around to all those weird projects we'd thought of, and not have to pander to the lowest common denominator just to stay afloat!" Of course, only some of those high-risk projects will become the next big thing, but a large number of trials is required to find highly improbable things. When companies are fighting each other tooth-and-nail, a single bad decision could sink them for good, which makes companies in highly competitive situations much more risk-averse. Conversely, when you control the market, you can make all sorts of investments that go nowhere and still survive -- and it is this large number of attempts that boosts the expected number of successes. With that said, let's review just a little bit of history impressionistically, and then turn to a new dataset that confirms the qualitative picture. Taking only a whirlwind tour through the pre-Information Age time period, we'll just note that most major inventions could not have been born if the inventor had not been protected from competitive market forces -- usually from protection by a monopolistic and rich political entity. Royal patronage is one example. And before the education bubble, there weren't very many large research universitities in your country where you could carry out research -- for example, Oxford, Cambridge, and... well, that's about it, stretching back 900 years. They don't call it "the Ivory Tower" for nothing. Looking a bit more at recent history, which is most relevant to any present debate we may have about the pros and cons of monopolies, just check out the Wikipedia article on Bell Labs, the research giant of AT&T that many considered the true Ivory Tower during its hey-day from roughly the 1940s through the early 1980s. From theoretical milestones such as the invention of information theory and cryptography, to concrete things like transistors, lasers, and cell phones, they invented the bulk of all the really cool shit since WWII. They were sued for antitrust violations in 1974, lost in 1982, and were broken up by 1984 or '85. Notice that since then, not much has come out -- not just from Bell Labs, but at all. The same holds true for the Department of Defense, which invented the modern airliner and the internet, although they made large theoretical contributions too. For instance, the groundwork for information criteria -- one of the biggest ideas to arise in modern statistics, which tries to measure the discrepancy between our scientific models and reality -- was laid by two mathematicians working for the National Security Agency (Kullback and Leibler). And despite all the crowing you hear about the Military-Industrial Complex, only a pathetic amount actually goes to defense (which includes R&D) -- most goes to human resources, AKA bureaucracy. Moreover, this trend goes back at least to the late 1960s. Here is a graph of how much of the defense outlays go to defense vs. human resources (from here, Table 3.1; 2008 and beyond are estimates):  There are artificial peaks during WWII and the Korean War, although it doesn't decay very much during the 1950s and '60s, the height of the Cold War and Vietnam War. Since roughly 1968, though, the chunk going to actual defense has plummeted pretty steadily. This downsizing of the state began long before Thatcher and Reagan were elected -- apparently, they were jumping on a bandwagon that had already gained plenty of momentum. The key point is that the state began to give up its quasi-monopolistic role in doling out R&D dollars. Update: I forgot! There is a finer-grained category called "General science, space, and technology," which is probably the R&D that we care most about for the present purposes. Here is a graph of the percent of all Defense outlays that went to this category:  This picture is even clearer than that of overall defense spending. There's a surge from the late 1950s up to 1966, a sharp drop until 1975, and a fairly steady level from then until now. This doesn't alter the picture much, but removes some of the non-science-related noise from the signal. [End of update] Putting together these two major sources of innovation -- Bell Labs and the U.S. Defense Department -- if our hypothesis is right, we should expect lots of major inventions during the 1950s and '60s, even a decent amount during the 1940s and the 1970s, but virtually squat from the mid-1980s to the present. This reflects the time periods when they were more monopolistic vs. heavily downsized. What data can we use to test this? Popular Mechanics just released a neat little book called Big Ideas: 100 Modern Inventions That Have Changed Our World. They include roughly 10 items in each of 10 categories: computers, leisure, communication, biology, convenience, medicine, transportation, building / manufacturing, household, and scientific research. They were arrived at by a group of around 20 people working at museums and universities. You can always quibble with these lists, but the really obvious entries are unlikely to get left out. There is no larger commentary in the book -- just a narrow description of how each invention came to be -- so it was not conceived with any particular hypothesis about invention in mind. They begin with the transistor in 1947 and go up to the present. Pooling inventions across all categories, here is a graph of when these 100 big ideas were invented (using 5-year intervals):  What do you know? It's exactly what we'd expected. The only outliers are the late-1990s data-points. But most of these seemed to be to reflect the authors' grasping at straws to find anything in the past quarter-century worth mentioning. For example, they already included Sony's Walkman (1979), but they also included the MP3 player (late 1990s) -- leaving out Sony's Discman (1984), an earlier portable player of digitally stored music. And remember, each category only gets about 10 entries to cover 60 years. Also, portable e-mail gets an entry, even though they already include "regular" e-mail. And I don't know what Prozac (1995) is doing in the list of breakthroughs in medicine. Plus they included the hybrid electric car (1997) -- it's not even fully electric! Still, some of the recent ones are deserved, such as cloning a sheep and sequencing the human genome. Overall, though, the pattern is pretty clear -- we haven't invented jackshit for the past 30 years. With the two main monopolistic Ivory Towers torn down -- one private and one public -- it's no surprise to see innovation at a historic low. Indeed, the last entries in the building / manufacturing and household categories date back to 1969 and 1974, respectively. On the plus side, Microsoft and Google are pretty monopolistic, and they've been delivering cool new stuff at low cost (often for free -- and good free, not "home brew" free). But they're nowhere near as large as Bell Labs or the DoD was back in the good ol' days. I'm sure that once our elected leaders reflect on the reality of invention, they'll do the right thing and pump more funds into ballooning the state, as well as encouraging Microsoft, Google, and Verizon to merge into the next incarnation of monopoly-era AT&T. Maybe then we'll get those fly-to-the-moon cars that we've been expecting for so long. I mean goddamn, it's almost 2015 and we still don't have a hoverboard. Labels: Economics, History, politics, Technology |