|

Friday, February 13, 2009

Slate has a piece up, Pregnant Pause: Who should pay for in vitro fertilization?. What might the objection to the bolded section be?:

Roughly 10 percent of couples experience infertility, a rate possibly accelerated by the increasing average age of prospective mothers. This demographic trend of older mothers is encouraging (since higher maternal age is a powerful predictor of financial security and the child's future social and educational attainment), but the odds of successful spontaneous pregnancy are lower. And so women increasingly turn to fertility treatments such as ovarian hyperstimulation, which forces the ovaries to pump out more eggs per cycle and increases the risk of having twins or triplets, and IVF, in which fertilized eggs, or embryos, are implanted in the uterus directly. Almost one in 80 newborns in the United States owes his existence to IVF. In any case, if there is mandatory insurance coverage for IVF that would seem to have obvious social consequences in terms of the decision-calculus that women make. The magnitude of the trade-offs shift.... Labels: Bioethics

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

The subtitle, The Case for Genetic Screening, seems to say it all. But Cowan comes at the topic as an historian with an interest in medical ethics. Here's how she makes her case:

1. She shows that historically the folks who came up with eugenics were different from the folks who came up with genetic screening. She is aware of the possibility of genetic fallacy, but I think she knows that people like it when their ideas flow from pure springs. She focuses on Tay-Sachs, beta-thalassemia, sickle-cell anemia, and PKU, showing that with the partial exception of sickle-cell, the drive for genetic testing came from parents whose children suffered from genetic diseases and from communities at high risk for the genetic disease. Thus, genetic screening is a bottom-up social phenomenon, not a top-down mandate. For the beta-thalassemia chapter, she spent some time on Cyprus, where the disease is relatively common, and her on-the-ground knowledge shows. 2. She shows that from a population genetics point of view there's a big difference between eugenics and genetic screening. Eugenics, she says, is a system of encouraging the fit to bear more children and perhaps discouraging or preventing the unfit from bearing children. Eugenics thus promotes 'good genes' in the population, the literal translation of eugenics. Modern genetic screening, by contrast, makes it easier for those with bad genes to bear children for two reasons. First, screening lets people with deleterious recessives find partners without such recessives, so the recessive alleles still stay in the population. Second, screening makes couples who both have the same deleterious recessive allele more willing to bear children, since they know they can abort a homozygotic recessive fetus. She actually has some decent anecdotal data on the second point. Thus, she repeatedly emphasizes that genetic screening is simultaneously "anti-eugenic" and "pro-natalist." 3. She tells a lot of human-interest stories about important firsts in genetic screening, focusing on happy endings. Given the importance of the law of small numbers, this is probably a good idea, and it's a relatively painless way for her to show how science and medicine work in the real world. The book is exceptionally well-written, and while her history of eugenics contains few surprises, her history of the successes and failures of genetic screening was quite gripping. She also covers the basics of Mendel from scratch, so feel free to hand the book to anyone who took high-school biology. Functionally, Cowan does the same thing for genetic screening that The New Republic did for tough-on-crime policies in the 80's and 90's: Cowan does some liberal hand-wringing while telling the reader that no, you're not becoming a Brownshirt if you agree to an amnio..... Related: Heredity and Hope: The Case for Genetic Screening by Ruth Schwartz Cowan. Labels: Bioethics

Monday, June 09, 2008

Engineering Life: The Dog that Didn't Bark in the Night:

...Erwin Chargaff, an eminent Columbia University biologist, called genetic engineering "an irreversible attack on the biosphere." Labels: Bioethics

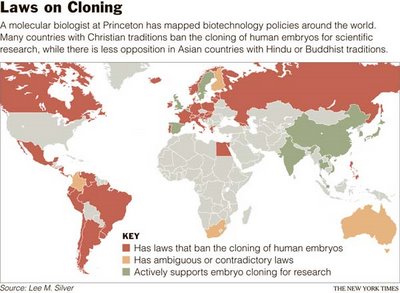

Monday, November 19, 2007

An article in The New York Times, Are Scientists Playing God? It Depends on Your Religion, surveys attitudes toward cloning and biological engineering in general. Roughly the thesis being reported is that there is a trichotomy between post-Christian societies, traditional Christian societies and those where Eastern religions predominate. Generally I'm skeptical of these grand cultural typologies, but in this case I think there is an underlying component that explains a large part of the trend: the Roman Catholic Church has long opposed many forms of biological intervention and will no doubt oppose many forms of biological engineering which it deems unethical. Though I do not doubt the sincerity of the believers of the Roman Catholic religion in their adherence to their Church's position here, I think this is a case where the elite formulation of the clergy and intellectuals has really made a significant impact on public policy. Reading about the anti-abortion movement in the United States during early days after Roe vs. Wade it is clear that the Roman Catholics were at the forefront, and fundamentalist Protestants joined the fray quite a bit later. Similarly, when it came to eugenics laws they were quite widespread in Protestant countries, but the Catholic Church threw up a concerted and consistent resistance to them in nations where it was an institution which could affect public policy significantly. An article in The New York Times, Are Scientists Playing God? It Depends on Your Religion, surveys attitudes toward cloning and biological engineering in general. Roughly the thesis being reported is that there is a trichotomy between post-Christian societies, traditional Christian societies and those where Eastern religions predominate. Generally I'm skeptical of these grand cultural typologies, but in this case I think there is an underlying component that explains a large part of the trend: the Roman Catholic Church has long opposed many forms of biological intervention and will no doubt oppose many forms of biological engineering which it deems unethical. Though I do not doubt the sincerity of the believers of the Roman Catholic religion in their adherence to their Church's position here, I think this is a case where the elite formulation of the clergy and intellectuals has really made a significant impact on public policy. Reading about the anti-abortion movement in the United States during early days after Roe vs. Wade it is clear that the Roman Catholics were at the forefront, and fundamentalist Protestants joined the fray quite a bit later. Similarly, when it came to eugenics laws they were quite widespread in Protestant countries, but the Catholic Church threw up a concerted and consistent resistance to them in nations where it was an institution which could affect public policy significantly.There are also specific and general problems with the typology. Consider the specific: Asia offers researchers new labs, fewer restrictions and a different view of divinity and the afterlife. In South Korea, when Hwang Woo Suk reported creating human embryonic stem cells through cloning, he did not apologize for offending religious taboos. He justified cloning by citing his Buddhist belief in recycling life through reincarnation. Hwang Woo Suk is a convert from Christianity to Buddhism. South Korea is a nation that is about 1/2 non-affiliated, 1/4 Buddhist and 1/4 Christian. Its ethical culture has been traditionally dominated by Confucianism, and there is a powerful substratum of indigenous shamanistic religion which suffuses the practices and outlooks of Christians & Buddhists alike. Christianity is gaining ground among the youth and in the educated segment of the population, and is the dominant religion in Seoul. The last two presidents of South Korea have been Roman Catholic, and that denomination is generally considered the most well educated, affluent and liberal of the religious pillars in South Korean society. South Korea also sends out the most Christian missionaries to the rest of the world aside from the United States. Christian fundamentalists in South Korea have even engaged in iconoclastic violence against Buddhist religious art and statuary. And yet South Koreans were also rather proud of their "cloning research." Then there is the biggest general issue with the typology: By contrast, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, God is the master creator who gives out new souls to each individual human being and gives humans "dominion over soul-less plants and animals. To traditional Christians who consider an embryo to be a human being with a soul, it is wrong for scientists to use cloning to create human embryos or to destroy embryos in the course of research. I think the term Judeo-Christian is stupid. In any case, not only are there very few Jews in the world, their attitude toward biological engineering tends to be pragmatic and consequentialist from what I can tell. There is one religious group which is left out the typology: Islam. About 15-20% of the world's population this seems like a large oversight. There don't seem to be many laws about cloning in the Muslim world, but take a look at abortion laws. Their objection to interventions might be less coherent or precise than those of Roman Catholics, but they seem to mirror them pretty well. The New York Times piece also points out that in the post-Christian world, such as Sweden, there is a fear of some sorts of biological changes due to a resurgence in a form of natural religion or spirituality. This shouldn't surprise; the decline of institutional Christianity in northern and eastern Europe has been met with both a rise in a scientific materialist outlook, but even more significantly an unspecified monistic theism reminiscent of pre-Christian traditions. The Left-Right convergences alluded too suggest to me that the typology is too coarse and inchoate. There is a universal "Yuck" within our species, probably rooted in our cognitive hardware. Channeling the impulses culturally can be a tricky thing. For instance, the Japanese and Israelis are far less advanced than Americans in their acceptance or practice of organ donation, generally due to religious rationales. Obviously the Japanese and Israelis don't share a common spiritual root or background. Note: I place an emphasis on the Catholic Church as an institution affecting public policy because, for example, abortion rates of Catholics in the United States are at the national average. Moral suasion can only go so far, especially when individuals are making personal utility calculations. Labels: Bioethics |