|

Thursday, January 21, 2010

What era are our intuitions about elites and business adapted to?

posted by

agnostic @ 1/21/2010 01:36:00 AM

Well, just the way I asked it, our gut feelings about the economically powerful are obviously not a product of hunter-gatherer life, given that such societies have minimal hierarchy, and so minimal disparities in power, material wealth, privileges of all kinds, etc. Hunter-gatherers don't even tolerate would-be elite-strivers, so beyond a blanket condemnation of trying to be a big-shot, they don't have the subtler attitudes that agricultural and industrial people do -- these latter groups tolerate and somewhat respect elites but resent and envy them at the same time.

So that leaves two major eras -- agricultural and industrial societies. I'm going to refer to these instead by terms that North, Wallis, & Weingast use in their excellent book Violence and Social Orders. Their framework for categorizing societies is based on how violence is controlled. In the primitive social order -- hunter-gatherer life -- there are no organizations that prevent violence, so homicide rates are the highest of all societies. At the next step up, limited-access social orders -- or "natural states" that sprung up with agriculture -- substantially reduce the level of violence by giving the violence specialists (strongmen, mafia dons, etc.) an incentive to not go to war all the time. Each strongman and his circle of cronies has a tacit agreement with the other strongmen -- who all make up a dominant coalition -- that I'll leave you to exploit the peasants living on your land if you leave me to exploit the peasants on my land. This way, the strongman doesn't have to work very much to live a comfortable life -- just steal what he wants from the peasants on his land, and protect them should violence break out. Why won't one strongman just raid another to get his land, peasants, food, and women? Because if this type of civil war breaks out, everyone's land gets ravaged, everyone's peasants can't produce much food, and so every strongman will lose their easy source of free goodies (rents). The members of the dominant coalition also agree to limit access to their circle, to limit people's ability to form organizations, etc. If they let anybody join their group, or form a rival coalition, their slice of the pie would shrink. And this is a Malthusian economy, so the pie isn't going to get much bigger within their lifetimes. So by restricting (though not closing off) access to the dominant coalition, each member maintains a pretty enjoyable size of the rents that they extract from the peasants. Why wouldn't those outside the dominant coalition not try to form their own rival group anyway? Because the strongmen of the area are already part of the dominant coalition -- only the relative wimps could try to stage a rebellion, and the strongmen would immediately and violently crush such an uprising. It's not that one faction of the coalition will never raid another, just that this will be rare and only when the target faction has lost some of its share in the balance of power -- maybe they had 5 strongmen but now only 1. Obviously the other factions aren't going to let that 1 strongman enjoy the rents that 5 were before, while they enjoy average rents -- they're going to raid him and take enough so that he's left with what seems his fair share. Aside from these rare instances, there will be a pretty stable peace. There may be opportunistic violence among peasants, like one drunk killing another in a tavern, but nothing like getting caught in a civil war. And they certainly won't be subject to the constant threat of being killed and their land burned in a pre-dawn raid by the neighboring tribe, as they would face in a stateless hunter-gatherer society. As a result, homicide rates are much lower in these natural states than in stateless societies. Above natural states are open-access orders, which characterize societies that have market economies and competitive politics. Here access to the elite is open to anyone who can prove themselves worthy -- it is not artificially restricted in order to preserve large rents for the incumbents. The pie can be made bigger with more people at the top, since you only get to the top in such societies by making and selling things that people want. Elite members compete against each other based on the quality and price of the goods and services they sell -- it's a mercantile elite -- rather than based on who is better at violence than the others. If the elites are flabby, upstarts can readily form their own organizations -- as opposed to not having the freedom to do so -- that, if better, will dethrone the incumbents. Since violence is no longer part of elite competition, homicide rates are the lowest of all types of societies. OK, now let's take a look at just two innate views that most people have about how the business world works or what economic elites are like, and see how these are adaptations to natural states rather than to the very new open-access orders (which have only existed in Western Europe since about 1850 or so). One is the conviction, common even among many businessmen, that market share matters more than making profits -- that being more popular trumps being more profitable. The other is most people's mistrust of companies that dominate their entire industry, like Microsoft in computers. First, the view that capturing more of the audience -- whether measured by the portion of all sales dollars that head your way or the portion of all consumers who come to you -- matters more than increasing revenues and decreasing costs -- boosting profits -- remains incredibly common. Thus we always hear about how a start-up must offer their stuff for free or nearly free in order to attract the largest crowd, and once they've got them locked in, make money off of them somehow -- by charging them later on, by selling the audience to advertisers, etc. This thinking was widespread during the dot-com bubble, and there was a neat management-oriented book written about it called The Myth of Market Share. Of course, that hasn't gone away since then, as everyone says that "providers of online content" can never charge their consumers. The business model must be to give away something cool for free, attract a huge group of followers, and sell this audience to advertisers. (I don't think most people believe that charging a subset for "premium content" is going to make them rich.) For example, here is Felix Salmon's reaction to the NYT's official statement that they're going to start charging for website access starting in 2011: Successful media companies go after audience first, and then watch revenues follow; failing ones alienate their audience in an attempt to maximize short-term revenues. Wrong. YouTube is the most popular provider of free media, but they haven't made jackshit four years after their founding. Ditto Wikipedia. The Wall Street Journal and Financial Times websites charge, and they're incredibly profitable -- and popular too (the WSJ has the highest newspaper circulation in the US, ousting USA Today). There is no such thing as "go after audiences" -- they must do that in a way that's profitable, not just in a way that makes them popular. If you could "watch revenues follow" by merely going after an audience, everyone would be billionaires. The NYT here seems to be voluntarily giving up on all its readers outside the US, who can’t be reasonably expected to have the ability or inclination to pay for web access. It had the opportunity to be a global newspaper, leveraging both the NYT and the IHT brands, and has now thrown that away for the sake of short-term revenues. This sums up the pre-industrial mindset perfectly: who cares about getting paid more and spending less, when what truly matters is owning a brand that is popular, influential, and celebrated and sucked up to? In a natural state, that is the non-violent path to success because you can only become a member of the dominant coalition by knowing the right in-members. They will require you to have a certain amount of influence, prestige, power, etc., in order to let you move up in rank. It doesn't matter if you nearly bankrupt yourself in the process of navigating these personalized patron-client networks because once you become popular and influential enough, you stand a good chance of being allowed into the dominant coalition and then coasting on rents for the rest of your life. Clearly that doesn't work in an open-access, competitive market economy where interactions are impersonal rather than crony-like. If you are popular and influential while paying no attention to costs and revenues, guess what -- there are more profit-focused competitors who can form rival companies and bulldoze over you right away. Again look at how spectacularly the WSJ has kicked the NYT's ass, not just in crude terms of circulation and dollars but also in terms of the quality of their website. They broadcast twice-daily video news summaries and a host of other briefer videos, offer thriving online forums, and on and on. Again, in the open-access societies, those who achieve elite status do so by competing on the margins of quality and price of their products. You deliver high-quality stuff at a low price while keeping your costs down, and you scoop up a large share of the market and obtain prestige and influence -- not the other way around. In fairness, not many practicing businessmen fall into this pre-industrial mindset because they won't be practicing for very long, just as businessmen who cried for a complete end to free trade would go under. It's mostly cultural commentators who preach the myth of market share, going with what their natural-state-adapted brain reflexively believes. Next, take the case of how much we fear companies that comes to dominate their industry. People freak out because they think the giant, having wiped out the competitors, will enjoy a carte blanche to exploit them in all sorts of ways -- higher prices, lower output, shoddier quality, etc. We demand the protector of the people to step in and do something about it -- bust them up, tie them down, resurrect their dead competitors, just something! That attitude is thoroughly irrational in an open-access society. Typically, the way you get that big is that you provided customers with stuff that they wanted at a low price and high quality. If you tried to sell people junk that they didn't want at a high price and terrible quality, guess how much of the market you will end up commanding. That's correct: zero. And even if such a company grew complacent and inertia set in, there's nothing to worry about in an open-access society because anyone is free to form their own rival organization to drive the sluggish incumbent out. The video game industry provides a clear example. Atari dominated the home system market in the late '70s and early '80s but couldn't adapt to changing tastes -- and were completely destroyed by newcomer Nintendo. But even Nintendo couldn't adapt to the changing tastes of the mid-'90s and early 2000s -- and were summarily dethroned by newcomer Sony. Of course, inertia set in at Sony and they have recently been displaced by -- Nintendo! It doesn't even have to be a newcomer, just someone who knows what people want and how to get it to them at a low price. There was no government intervention necessary to bust up Atari in the mid-'80s or Nintendo in the mid-90s or Sony in the mid-2000s. The open and competitive market process took care of everything. But think back to life in a natural state. If one faction obtained complete control over the dominant coalition, the ever so important balance of power would be lost. You the peasant would still be just as exploited as before -- same amount of food taken -- but now you're getting nothing in return. At least before, you got protection just in case the strongmen from other factions dared to invade your own master's land. Now that master serves no protective purpose. Before, you could construe the relationship as at least somewhat fair -- he benefited you and you benefited him. Now you're entirely his slave; or equivalently, he is no longer a partial but a 100% parasite. You can understand why minds that are adapted to natural states would find market domination by a single or even small handful of firms ominous. It is not possible to vote with your dollars and instantly boot out the market-dominator, so some other Really Strong Group must act on your behalf to do so. Why, the government is just such a group! Normal people will demand that vanquished competitors be restored, not out of compassion for those who they feel were unfairly driven out -- the public shed no tears for Netscape during the Microsoft antitrust trial -- but in order to restore a balance of power. That notion -- the healthy effect for us normal people of there being a balance of power -- is only appropriate to natural states, where one faction checks another, not to open-access societies where one firm can typically only drive another out of business by serving us better. By the way, this shows that the public choice view of antitrust law is wrong. The facts are that antitrust law in practice goes after harmless and beneficial giants, hamstringing their ability to serve consumers. There is little to no evidence that such beatdowns have boosted output that had been falling, lowered prices that had been rising, or improved quality that had been eroding. Typically the lawsuits are brought by the loser businesses who lost fair and square, and obviously the antitrust bureaucrats enjoy full employment by regularly going after businesses. But we live in a society with competitive politics and free elections. If voters truly did not approve of antitrust practices that beat up on corporate giants, we wouldn't see it -- the offenders would be driven out of office. And why is it that only one group of special interests gets the full support of bureaucrats -- that is, the loser businesses have influence with the government, while the winner business gets no respect. How can a marginal special interest group overpower an industry giant? It must be that all this is allowed to go on because voters approve of and even demand that these things happen -- we don't want Microsoft to grow too big or they will enslave us! This is a special case of what Bryan Caplan writes about in The Myth of the Rational Voter: where special interests succeed in buying off the government, it is only in areas where the public truly supports the special interests. For example, the public is largely in favor of steel tariffs if the American steel industry is suffering -- hey, we gotta help our brothers out! They are also in favor of subsidies to agribusiness -- if we didn't subsidize them, they couldn't provide us with any food! And those subsidies are popular even in states where farming is minimal. So, such policies are not the result of special interests hijacking the government and ramrodding through policies that citizens don't really want. In reality, it is just the ignorant public getting what it asked for. It seems useful when we look at the systematic biases that people have regarding economics and politics to bear in mind what political and economic life was like in the natural state stage of our history. Modern economics does not tell us about that environment but instead about the open-access environment. (Actually, there's a decent trace of it in Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments, which mentions cabals and factions almost as much as Machiavelli -- and he meant real factions, ones that would war against each other, not the domesticated parties we have today.) We obviously are not adapted to hunter-gatherer existence in these domains -- we would cut down the status-seekers or cast them out right away, rather than tolerate them and even work for them. At the same time, we evidently haven't had enough generations to adapt to markets and governments that are both open and competitive. That is certain to pull our intuitions in certain directions, particularly toward a distrust of market-dominating firms and toward advising businesses to pursue popularity and influence more than profitability, although I'm sure I could list others if I thought about it longer. Labels: Economic History, Economics, Evolutionary Psychology, History, politics, Psychology

Sunday, January 17, 2010

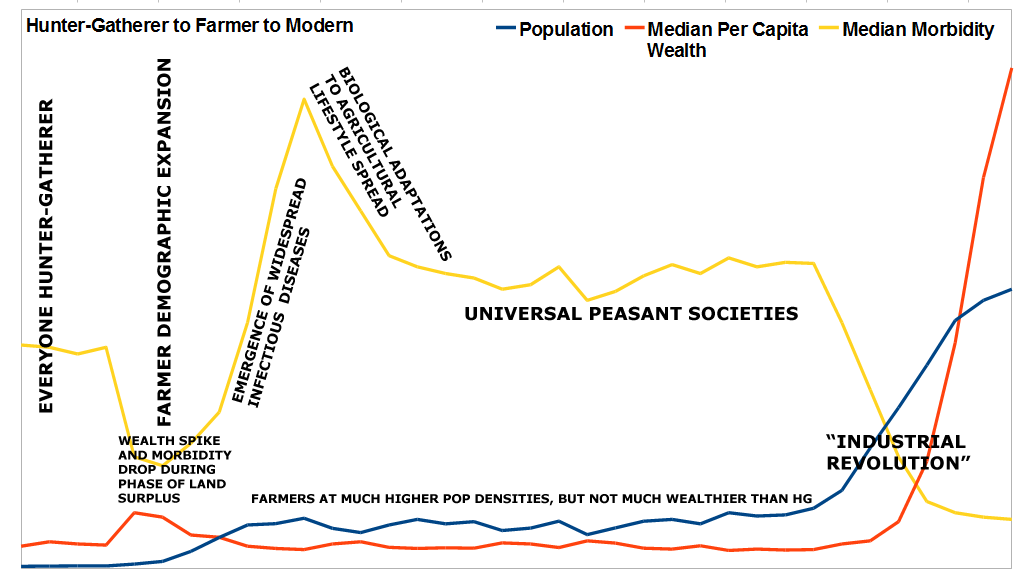

In the comments below I was outlining a simple model which really is easiest to communicate with a chart. I removed the labels on the Y and X axes because the details don't matter, the X axis is simply "time," and the Y axis simply reflects the magnitudes of the three trendlines. The key is to focus on the relationship between the three. I've labeled for clarity, but more verbal exposition below....

For most of the human history we've been hunter-gatherers. But over the past 10,000 years there was a switch in lifestyle, farming has emerged independently in several locations, and filled in all the territory in between. One truism of modern cultural anthropology is that this was a big mistake, that hunter-gatherer lifestyles were superior to those of peasant farmers, less miserable with much more free time. I think this is somewhat unsubtle, which is ironic since cultural anthropologists really love to deconstruct the errors of others which they themselves are guilty of (i.e., in this case, the normative aspect immediately jumps out in the scholarship. There's little doubt as to who they're "rooting" for). I am willing to grant that the median hunter-gatherer exhibits somewhat less morbidity than the median farmer. They're taller and have better teeth than farmers. Compared to modern people living in developed countries though the differences will seem trivial, so remember that we're talking on the margins here. So why did societies transition from hunter-gathering to farming? I doubt there's one simple answer, but there are some general facts which are obvious. There's plenty of evidence that farming supports many more people per unit of land, so in pure demographic terms hunter-gathering was bound to be doomed. They didn't have the weight of numbers. But why did the initial farmers transition from being hunter-gatherers to farmers in the first place? Because I think that farming was initially the rational individual choice, and led to more potential wealth and reproductive fitness. Remember, there's a big difference between existing in a state of land surplus and one of labor surplus. American farmers were among the healthiest and most fertile human populations which had ever lived before the modern era. Pioneers had huge families, and continued to push out to the frontier. This was not the lot of Russian serfs or Irish potato farmers. But eventually frontiers close, and Malthusian logic kicks in. The population eventually has nowhere to go, and the surplus of land disappears. At this point you reach a "stationary state," where a peasant society oscillates around its equilibrium population. I suspect that new farming populations which slam up against the Malthusian limit suffered even more misery than their descendants. This is because I believe that their demographic explosion had outrun their biological and cultural capacity to respond to the consequences of the changes wrought upon their environment. First and foremost, disease. During the expansionary phase densities would have risen, and infectious diseases would have begun to take hold. But only during the stationary state would they become truly endemic as populations become less physiologically fit due to nutritional deficiencies. The initial generations of farmers who reached the stationary state would have been ravaged by epidemics, to which they'd only slowly develop immunological responses (slowly on a human historical scale, though fast on a evolutionary one). This is even evident in relatively recent historical period; Italians developed biological and cultural adaptations to the emergence of malaria after the fall of Rome (in terms of culture, there was a shift toward settlement in higher locations). But there would be more to adapt to than disease. Diet would be a major issue. During the expansionary phase it seems plausible that farmers could supplement their cereal based diet with wild game. But once they hit the stationary phase they would face the trade-off between quantity and quality in terms of their foodstuffs. Hunter-gathering is relatively inefficient, and can't extract as many calories per unit out of an acre (at least an order of magnitude less), but the diet tends to be relatively balanced, rich in micronutrients, and often fats and protein as well. The initial shock to the physiology would be great, but over time adaptations would emerge to buffer farmers somewhat from the ill effects of their deficiencies. This is one hypothesis for the emergence of light skin, as a way to synthesize vitamin D endogenously, as well as greater production of enzymes such as amylase and persistence of lactase, which break down nutrients which dominate the diet of agriculturalists. Once societies reached a stationary state it would take great shocks to push them to a position where becoming hunter-gatherers again might be an option. A population drop of 50%, not uncommon due to plague or political collapse, would still not be low enough so that the remaining individuals would be able to subsist upon game and non-cultivated plant material. Additionally the ecology would surely have been radically altered so that many of the large game animals which might have been the ideal sources of sustenance in the past would be locally extinct. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the highland Maya city-states seems to have resulted in lower population densities and reduced social complexity, but in both regions agriculture remained dominant. On the other hand, there is some evidence that the Mississippian societies might have experienced die offs on the order of 90% due to contact with Spanish explorers, and later ethnography by European settlers suggests much simpler tribal societies than what the Spaniards had encountered. Though these tribal groupings, such as the Creeks, still knew how to farm, it seems that judging from the conflicts which emerged due to European encroachment on hunting grounds that this population drop was great enough to allow for a greater reversion to the pre-agricultural lifestyle than was able to occur elsewhere. But then the pre-Columbian exchange and the exposure of native populations to the 10,000 years of Eurasian pathogen evolution was to some extent a sui generis event. The model I highlight above is very stylized, and I am aware that most societies go through multiple cycles of cultural, and possibly biological, adaptation. The putative massive die off of native populations of the New World may have resulted in a reversion to simpler hunter-gatherer cultural forms in many regions (North America, the Amazon), and also reduced morbidity as diets once more became diversified and indigenous infectious diseases abated due to increased physiological health and decreased population density. In China between 1400 and 1800 there was a massive expansion of population beyond the equilibrium established between the Han and Song dynasties. The reasons for this are manifold, but one was perhaps the introduction of New World crops. Clearly in Ireland the introduction of the potato initially resulted in greater health for the population of that island, as in the 18th century the Irish were taller than the English because of their enthusiastic adoption of the new crop. Over the long term, at least from the perspective of contemporary humans, agriculture was not a disaster. Dense populations of farmers eventually gave rise to social complexity and specialization, and so greater productivity. Up until the 19th century productivity gains were invariably absorbed by population growth or abolished by natural responses (e.g., in the latter case Sumerian irrigation techniques resulted in gains in productivity, but these were eventually diminished by salinization which entailed a shift from wheat to barley, and eventually an abandonment of many fields). Additionally, the rise of mass society almost immediately birthed kleptocratic rentier classes, as well as rigid social forms which constrained human individual choice and possibilities for self-actualization. The noble savage who lives in poverty but has freedom may look ludicrous to us today, but from the perspective of an 18th century peasant who lives in poverty but has no freedom it may seem a much more appealing model (though these sorts of ideas were in any case the purview of leisure classes).* But 10,000 years of crooks who innovate so that they could continue to steal more efficiently eventually gave rise to what we call modern capitalism, which broke out of the zero-sum mentality and banished Malthusian logic, at least temporarily (remember that it is critical to note that population growth leveled off after the demographic transition, which allowed us to experience the gains in productivity as wealth and not more humans). I should qualify this though by noting that we can't know if the emergence of modern capitalism was inevitable in a historical sense. It happened once in Western Europe, and has spread through the rest of the world through emulation (Japan) or demographic expansion (the United States). The only possible "close call" was Song China, which had many of the institutional and technological preconditions, but never made the leap (whether that was because of the nature of the Chinese bureaucratic state or the disruption of the Song path toward capitalism by the Mongol conquest, we'll never know). By contrast, the spread of agriculture was likely inevitable.** Agricultural emerged at least twice, in the Old and New World, and likely multiple times in the Old World. Kings, armies and literacy, and many of the accoutrements of what we would term "civilization" arose both in the Old and New World after the last Ice Age. In all likelihood a confluence of biological, cultural and ecological conditions which were necessary for the rise of agricultural civilization were all in place ten thousand years ago. This also suggests that certain biological adaptations (e.g., lactase persistence) were also inevitable. * Though from what I have read hunter-gatherers are strongly constrained by their own mores in a manner which rivals that of traditional peasant societies; only they have no priests who have written the customs down and serve as interpreters. Rather, it is the band (mob?) which arbitrates. ** We have data on independent shifts toward agricultural lifestyles. We don't have data on independent shifts toward modern capitalist economies. I suspect that the shift toward capitalism is probably inevitable over the long term because I don't think pre-modern agricultural civilizations would ever have been exploitative enough of the natural resource base that they would have been subject to worldwide collapse in any normal timescale. So there would always be potential civilizations from which modern post-Malthusian technological civilization could have emerged. Labels: Economic History

Thursday, November 19, 2009

This is more a question for readers who know this stuff, what do you think about Patricia Crone & company in their revision of the early history of Islam? I'm more of a Hugh Kennedy guy because I don't know much about this field and would prefer to stick to the mainstream, but a few years ago I read a short monograph on representational art in mid-Umayyad Syria, and it just didn't "feel right" in the context of the traditional narrative. The book didn't really talk much about history, but rather more the Late Antique cultural influences on the Umayyad's. But what I encountered seemed more like a conventional society of the post-Roman Near East than anything I would recognize as "Muslim." Of course it's all impressionistic, and I don't have a good feel of the lay of the land, so I dismissed it. But how about those of you who know the primary sources? I can't find Daniel Larison's opinion on this sort of revisionism via Google, and I would be curious has to his views (since he knows Byzantine history and its sources, and had an interest in Islam at some point as well).

Update: OK, probably crap. Update: OK, Larison might be talking about a somewhat different model. Labels: Economic History, Islam

Monday, October 26, 2009

Over at New Majority David Frum has a review up of Chris Wickham's The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages, 400-1000. Frum elaborates on one of Wickham's central theses about the nature of the fall of the Roman Empire, the shift from direct taxation to assignments of land (what eventually evolved into what we term 'feudalism'). Wickham's book has been discussed in detail on this weblog before, he works within a Marxist framework whereby impersonal social and economic forces loom large, so you won't get too much on battles as opposed to tax receipts.

But jumping forward in history 1,500 years I am struck by some of the same issues which crop up in the 18th century with the rise of the British Empire, and its ascendancy over continental powers such a France despite its smaller population (on the order of 1/3 France's population in the early 18th century I believe). The argument roughly runs that Britain constructed a military-financial complex, whereby it could utilize debt to finance its wars, while France was dependent on more conventional forms of direction taxation. This is a classic case of using leverage to beat an opponent which by all rights should have you outgunned on paper. The early American republic saw conflicts between those who wished to emulate the British state (Alexander Hamilton) and those who did not (Thomas Jefferson). We know who won that debate. In any case, it is important to remember that before 1800, and in particular before 1500, differences in per capita wealth between regions were trivial compared to what we see today. The most extreme differences in per capita wealth might be 50%, while something closer to 10-25% were much more typical. This is why Greg Clark asserts blithely that for almost all of human history per capita wealth remained approximately what it was when our species were all hunter-gatherers in Farewell to Alms. No, what was different between Rome and the "barbarian" lands beyond the limes had less to do with median differences in wealth, and more to do with how the wealth was allocated and leveraged. This is why, I think, nomad elites invariably invaded civilized states despite the likelihood that the average nomad was likely more affluent than the average peasant; civilized super-elites could extract much more surplus from their subjects than nomadic warlords could from their inferiors. Addendum: One thing want to add, structural and institutional innovations often only result in a transient advantage. For example, both Tim Blanning and Peter Turchin point out that the most consistent predictive variable for victories during the wars which erupted in Europe after the French Revolution was the size of armies. The initial victories of the French were simply a function of the revolutionary state's putting many more men under arms, while most of the European monarchies stuck longer with smaller professional armies. Once other states caught up the French advantage disappeared. But despite the fact that the equilibrium was restored after a generation, I think we can admit that the transient was very important as a "hinge of history." Labels: Economic History, Taxes

Monday, September 28, 2009

Life and death during the Great Depression:

Recent events highlight the importance of examining the impact of economic downturns on population health. The Great Depression of the 1930s was the most important economic downturn in the U.S. in the twentieth century. We used historical life expectancy and mortality data to examine associations of economic growth with population health for the period 1920-1940. We conducted descriptive analyses of trends and examined associations between annual changes in health indicators and annual changes in economic activity using correlations and regression models. Population health did not decline and indeed generally improved during the 4 years of the Great Depression, 1930-1933, with mortality decreasing for almost all ages, and life expectancy increasing by several years in males, females, whites, and nonwhites. For most age groups, mortality tended to peak during years of strong economic expansion (such as 1923, 1926, 1929, and 1936-). In contrast, the recessions of 1921, 1930-1933, and 1938 coincided with declines in mortality and gains in life expectancy. The only exception was suicide mortality which increased during the Great Depression, but accounted for less than 2% of deaths. Correlation and regression analyses confirmed a significant negative effect of economic expansions on health gains. The evolution of population health during the years 1920–1940 confirms the counterintuitive hypothesis that, as in other historical periods and market economies, population health tends to evolve better during recessions than in expansions. Also see ScienceDaily. I guess these papers are seeing the light of day because they're "relevant" again, but apparently these sorts of counterintuitive data have been an open secret for a while. Labels: Economic History |