|

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Antitrust suits are brought by busted businesses, not consumer crusaders: Dairy edition

posted by

agnostic @ 9/23/2009 10:22:00 PM

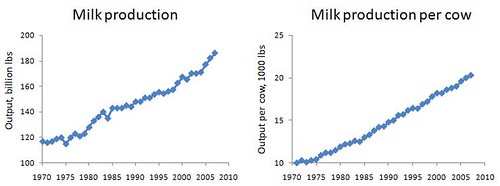

After reading Arthur De Vany's Hollywood Economics and Winners, Losers, and Microsoft by Stan Liebowitz and Stephen Margolis, I got the impression that antitrust cases on the whole have been misguided and often remarkably stupid. Looking a little more into it, I found that economists now are pretty much agreed on that picture. Here is the entry on antitrust from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, which has a nice brief list of references. Most cases are not brought by public representatives, whether elected or self-appointed, but by private companies, often rivals of the defendant who are being driven out of business. Businessmen believe that competition is good if they win but bad if the other guy wins. After reading Arthur De Vany's Hollywood Economics and Winners, Losers, and Microsoft by Stan Liebowitz and Stephen Margolis, I got the impression that antitrust cases on the whole have been misguided and often remarkably stupid. Looking a little more into it, I found that economists now are pretty much agreed on that picture. Here is the entry on antitrust from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, which has a nice brief list of references. Most cases are not brought by public representatives, whether elected or self-appointed, but by private companies, often rivals of the defendant who are being driven out of business. Businessmen believe that competition is good if they win but bad if the other guy wins.Because these facts are not widely known outside of economics circles, and because most of us learned bogus stories about Standard Oil, etc., in high school history class, I figured I'd illustrate them with a recent complaint about alleged anti-competitiveness in the dairy industry. The farmers on the losing side of the commercial contest claim one thing, but I show that the facts prove the opposite. First, here are free WSJ articles about the small farmers' complaints and a follow-up on the response of the DoJ's antitrust division. We can ignore the complaints of all the farmers quoted, as well as the talk from politicians in dairy states, because the very first sentence says that there is a "price-depressing glut of milk." A monopoly harms consumers by restricting output in order to shoot prices up -- think of a diamond company that owns almost all diamonds but only allows a tiny amount to get into circulation. So right away we see that there is the exact opposite of monopolistic practices in dairy -- there is a glut rather than a dearth of output, and prices are plummeting rather than soaring. Is the 2001 merger of two large dairy processors to "blame" for greater output and lower prices, as suggested by the complainers? No. The article doesn't provide a broader perspective, but I looked up data from the Statistical Abstract of the United States' agriculture tables. Here is the price of milk received by farmers from 1980 to 2009, both unadjusted and adjusted for inflation using the CPI:  There is clearly no change in the trend during or after 2001. The real price of milk has been falling at least since 1980, and in this decade it has actually slowed down -- it's "showing signs of stabilization," as we would hear in another context. The nominal price shows no trend up or down, just greater volatility starting around 1995. OK, what about output -- was the recent merger responsible for flooding the market? Let's have a look:  The left graph shows that output has been increasing steadily at least since 1970. The only somewhat recent change is that the increase appears to get faster around 1995, compared to its shallower rate from 1985 to 1995. Again we see no effect of the 2001 merger -- let alone a harmful downward one. The graph on the right shows the trend for milk cows' productivity, or output per cow: it too has been steadily increasing since at least 1970, probably due to some combination of better technology and selective breeding. Here there is no change whatsoever in the rate around 2001 -- it's basically linear after 1975. So we have greater output, lower prices, and greater productivity. What about having "too much" market share? The articles say that Dean Foods buys less than 15% of the nation's supply of raw fluid milk, which is hardly a concentration of the industry -- even if market concentration mattered per se (which it doesn't). It is a red herring that it has market shares closer to 70% or 80% in some regions -- it could not try to restrict output and thus raise prices in these regions anyway. Why not? If Dean Foods tried to gouge consumers in Michigan, anyone in Michigan could simply buy milk from a state where the supposed monopolistic gouging was absent, transport it to Michigan, and sell it below what the monopolist was charging. And -- boom -- just like that, competition neuters gouging. (Looking more generally, milk is a commodity like gold, so just imagine if Michigan residents were charged up the ass for gold, while Ohio residents weren't. You could get rich quick in Michigan by buying gold in Ohio and selling it in Michigan, low enough to undercut the monopolist but high enough to cover your costs. Since these get-rich-quick opportunities would quickly exhaust themselves and drive down the monopolist's prices, we don't expect to see such price-gouging even if the company did have an incredibly large market share.) But are the big bad companies even driving the little guy out of business? In my quick search, I didn't find data for this year, but a press release on the state of US agriculture in 2007 says that it's the middle-sized farms that are getting cleared out, suggesting greater specialization (like Wal-Marts co-existing with tiny local boutiques): The latest census figures show a continuation in the trend towards more small and very large farms and fewer mid-sized operations. Between 2002 and 2007, the number of farms with sales of less than $2,500 increased by 74,000. The number of farms with sales of more than $500,000 grew by 46,000 during the same period. Granted, this is for all farms, not just dairy farms, but I'd be surprised if the pattern were in the other direction for the subset of dairy farms. Again, even if it were, that might make us feel bad about small farmers going out of business, but it would not be evidence of monopoly, anti-competition, or whatever else. Output and productivity are going up, and prices are going down. It doesn't get any simpler than that. As the CEE antitrust entry notes, most lawsuits are brought by companies who are suppliers or buyers of the targeted company. That's what we have here, since Dean Foods buys milk from the embittered dairy farmers. The incentive to make it an antitrust suit is that they can win three times the damages than if they didn't. So the next time you hear about some company coming under antitrust scrutiny, just keep this big picture in mind. Pretty much all such cases are bogus. Rather than crusades in the consumers' interests, they are cowardly attempts by a loser to have the referee handicap the winner just as they're about to get knocked out. I encourage readers to look through some of the references in the CEE entry; it is quite illuminating to see how backwards the history of antitrust has been, and how baldly we were lied to in high school about Standard Oil and the rest.

Thursday, July 02, 2009

Catfish plan risks trade war:

It looks like catfish, it tastes like catfish, and it acts like catfish. It doesn't taste like catfish.

Tuesday, June 30, 2009

Some readers here may already follow the food-related stuff I write about at my personal blog. Well, to allow myself to write more about diet, nutrition, and food in general, I've started a new blog called Low Carb Art and Science. Lord knows there are already lots of blogs that deal with the topic, but this one will have lots more data and a stronger emphasis on evolution. But there will be plenty of less serious stuff and easy recipes too. Plus I'll take an occasional interdisciplinary approach, as with an earlier post I wrote about the late Medieval shift away from carbs and toward meat.

The first post up is about the changing American diet and poorer health -- except that the graphs show that the changing American diet has been one that's rigidly adhered to what the health experts tell us to eat. The data weren't hard to find, analyze, and present, but I've never seen them before, let alone in a clear-to-see visual format. If you doubted whether the anti-meat, pro-grain message was being followed or not, and if so, whether it was making us healthier -- this will be a real eye-opener. Take-home lesson: eat more saturated fat and cholesterol, and less carbohydrates. Comments closed here; comment over at Low Carb Art and Science.

Thursday, June 25, 2009

In False Economy: A Surprising Economic History of the World* there's a chapter which covers "The Catfish War" between Vietnam and the United States in the early 2000s. Basically Vietnamese catfish were cheaper than American catfish, so American farmers got the government to force the Vietnamese to not label the fish catfish (it's a different species from the American variant). So Vietnamese catfish are now termed "basa" in the United States. Interestingly this might have backfired, the author of False Economy claims that many American consumers ended up thinking basa were an exotic premium import. But here's another reality: in blind taste tests people prefer Vietnamese catfish to American catfish.

I only mention this because I've been getting basa for a few weeks now. Today the supermarket was out of basa, but did have American catfish (where there used to be basa). So I got American catfish because I figured catfish is catfish. Well...American catfish kind of sucks compared to basa. I don't find catfish meat repellent or anything, but basa has a much nicer flavor and smell than American catfish. It's also easier to cook. And I don't have a subtle palette; I use a lot of hot sauce, so I can tolerate a large range in flavor. There just isn't any comparison. Perhaps it was a bad batch of catfish, but I've actually had catfish sandwiches and the like in New Orleans and Houston, and I think this was typical American catfish thinking back to that. Wikipedia said that people prefer basa to American catfish 3:1, but I would have expected 10:1. * It's a well written work which illustrates general economic principles with concrete contemporary examples, but is far inferior to Rondo Cameron's A Concise Economic History of the World in terms of factual density. Labels: Food |