|

Monday, November 16, 2009

It's easy to find maps of American ancestries, but I wanted to play around with the data, and in particularly the visualization myself. So I went to the Census and got the county level numbers. The first thing I wanted to do was look at non-Hispanic white ethnicities as a proportion of non-Hispanic whites. That would for example increase the Anglo-Saxon character of the lowland South because it would remove African Americans from the equation.

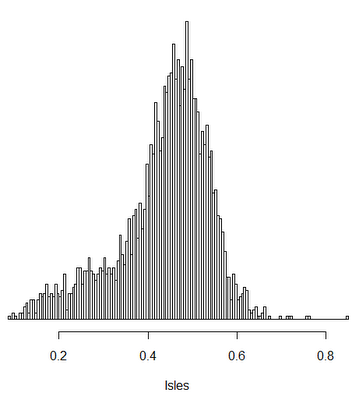

All the data was from the 2000 Census, and I simply divided the % of each European ancestry group by the non-Hispanic white percentage to reweight appropriately. Here are some correlations I found: English X Scots-Irish = 0.34 English X Irish = 0.30 English X American = -0.20 Scots-Irish X Irish = 0.37 Scots-Irish X American = -0.25 Irish X American = -0.45 I left the Scottish and Welsh out of this because their numbers were relatively small. One of the main issues with look at the "Irish" and "American" category is that both of these are probably heavily loaded with Scots-Irish. Below the fold are some maps I generated. Blue = above the median for the frequency of that group nationally (the median being calculated again with non-Hispanic whites only included). Red = below the median. The distributions of frequencies by county tend to be positively skewed, so the shading is covering a larger spectrum of frequencies in the blue than the red. Min = 1.6% 25% = 8.5% Median = 11% 75% = 14% Max = 48%  Min = 0% 25% = 1% Median = 2% 75% = 3% Max = 10%  Min = 2% 25% = 10% Median = 12% 75% = 14% Max = 37%  Min = 0% 25% = 7% Median = 14% 75% = 22% Max = 70%  "Isles" includes Scottish & Welsh, as well as "American." Min = 9% 25% = 39% Median = 44% 75% = 51% Max = 85%  Finally, here's a map where those of "Isles" origin are 50% or more of the non-Hispanic white population.  The shading for the "Isles" doesn't look right. But here's the histogram:  The median is 0.45. So that's probably why the blue is relatively homogeneous, the distribution is negatively skewed. Labels: geography

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Since Afghanistan is in the news a lot, I keep hearing about it. I decided to double check some numbers, and here's some weird stuff:

Afghanistan, 11 million Pashtuns, Pakistan, 27 million Pashtuns Azerbaijan, 8.1 million Azeris, Iran, 17.75 million Azeris Mongolia, 2.3 million Mongols, China, 5 million Mongols Labels: geography

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

Since most people use online social networks like Facebook to keep in touch with people who they interact with in real life, it doesn't make sense to sign up for a Facebook account unless others in your area have already. This predicts that we should see a spreading out of Facebook from its founding location, just like a contagious disease rolling out from Typhoid Mary's neighborhood. Let's take a look at the data and see.

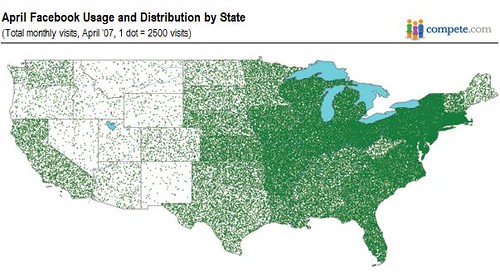

First, I found this map from Google Images of the number of Facebook visits by state:  Unfortunately, these are not per capita rates. But you can still tell that the Northeast has a whole hell of a lot of activity, while super-populated California shows little. Luckily, Facebook calculated the number of adult users in each state, and divided this by the state's entire adult population size to get the prevalence of Facebook among adults by state. The data are here, and I've made a bubble map of them here. Note that the pattern is pretty similar, even though these are now per capita rates. It looks as though Facebook is spreading from the Northeast, so one easy way to quantify the pattern is to plot the prevalence of Facebook among adults as a function of distance from the original physical site -- Harvard, in this case. (I used the zip code of a state's largest city and that of Harvard to calculate distance.) Here is the result:  Close to Harvard, prevalence is high, and it declines pretty steadily as you branch out from there. The Spearman rank correlation between Facebook prevalence and distance from Harvard is -0.58 (p less than 10^-6). If Facebook were being used to talk anonymously to a bunch of strangers, as with the early AOL chatrooms, then the adoption of this technology wouldn't show such a strong geographical pattern -- who cares if no one else in your state uses a chatroom, as long as there are enough people in total? This shows how firmly grounded in people's real lives their use of Facebook is; otherwise it would not spread in a more or less person-to-person fashion from its founding location. It's not that there aren't still chatrooms -- it's just that, to normal people, they're gay, at least compared to Facebook. Few would prefer joining a cyberworld for their social interaction -- using the internet to slightly enhance what they've already got going in real life is exciting enough. The only exceptions are cases where you have no place to congregate in real life with your partners, such as a group of young guys who want to play video games. Arcades started to vanish around 1988, so that now they must plug in to the internet and play each other online. For the most part, though, the internet isn't going to radically change how we conduct our social lives. Labels: culture, geography, Technology, web

Tuesday, June 19, 2007

A recent article in Nature, which we blogged about here, reviewed the consequences of agriculture on the nature and prevalence of pathogens that have plagued human beings. One key datum that Wolfe et al. (2007) discuss is the difference between the vectors (or transmitters) of infectious disease in the tropical vs. non-tropical regions, where agriculture has flourished the longest: almost all of the nasty infectious diseases in the tropics are spread by winged insects [1], whereas most of those in the more advanced areas are spread by human-to-human contact, polluted water, or parasites of small animals (such as the fleas that spread the Bubonic Plague). One consequence of this is that, as the authors note, infectious diseases in the tropics tend to be chronic rather than acute -- in crowded populations that characterize agricultural societies, it won't take long for you to pass your germs to someone nearby, after which point you've served your purpose and can be left alone for the time being (if you aren't shortly killed). If there aren't many people nearby to infect, you're going to have to serve as the host for much longer.

The authors do not note, however, an important evolutionary reason for why the geography of tropical regions causes them to be more plagued by insect-transmitted disease. This shortcoming is odd considering that one of the authors, Jared Diamond, has written best-selling books on human evolution (The Third Chimpanzee) and geography and civilization (Guns, Germs, and Steel). I haven't read either of these in full, so to be sure he didn't cover this issue in GGS, I searched it at Amazon and found no discussion of the prevalence of wingedness among insects. In any case, the key pattern is that the proportion of insects that are winged increases as both latitude and altitude decrease. At a more fine-grained level, wingedness is more common in habitats that are in some sense temporary or unstable, while flightlessness is more common in more permanent, stable habitats [2]. The basic insight comes from life history theory: in unstable habitats, an individual may be born into awful conditions due to temporal and/or spatial hetereogeneity. Here, it will pay to have a means of migrating to a more hospitable area, while in less volatile habitats an individual probably won't get caught with their pants down, and so flightlessness would increase. Just think of the energy a bug would save by not growing and maintaining their wings if it didn't need them. Most tropical areas have all three features: low in elevation, close to the equator, and more unstable habitat-wise [3]. It's no surprise, then, that such areas are more wracked by insect-borne infectious diseases. There are simply far more winged bugs that can travel far distances transmitting pathogens to humans. One consequence of all this chronic disease must surely be increased difficulty in founding, let alone maintaining, a great human civilization. Chronic diseases which begin to strike early on in life are likely one reason that mean sub-Saharan African IQ is about 70, while mean African-American IQ is about 85, a full standard-deviation above. Possible mechanisms are not difficult to think of: the parasite that causes Sleeping Sickness get into your brain and slowly destroys it, your body may divert resources to disease defense and repair rather than on "luxury" items like higher IQ, and so on. Even controlling for IQ, being afflicted with chronic disease must sap one's ability to doggedly pursue long-term projects, whether artistic or scientific, that foster civilization. Probably the best shot sub-Saharan Africa has is south of the Zambezi River, which doesn't suffer from a tropical hellhole climate. At best they could reach the level of African-Americans, who don't dominate Silicon Valley, but who have contributed scores more to the world's culture than Africans in sub-Saharan Africa. [4] Even in the US, most high African-American culture has largely sprung from cities outside of the dreadful "humid subtropical" climate of the Southeastern states (for example, New York and Chicago). That pattern is also evident among American Whites, by the way: at the most northern fringe of the Southeastern US there are first-rate research universities (Duke and UNC - Chapel Hill, both in North Carolina), but the region is largely bereft of civilization-propelling institutions. In fact, blogger Inductivist has shown, using General Social Survey data on Whites, that it is a larger source of and magnet for duller Whites, compared to other regions (see here and here). Now, clearly I'm not proposing that epidemic Sleeping Sickness, malaria, etc. are causing the problem in the US. But whatever the more numerous bugs in the Southeast are transmitting to humans, it could partially account for the discrepancy between its level of culture and that of the Northeast. Indeed, from Inductivist's reckoning, it appears that most intelligent people with any sense from that region decide to haul ass to the Mid-Atlantic and New England states. [1] From p. 280 of Wolfe et al: A higher proportion of the diseases is transmitted by insect vectors in the tropics (8/10) than in the temperate zones (2/15) (P less than 0.005, chi-square test, degrees of freedom, d.f. = 51). This difference may be partly related to the seasonal cessations or declines of temperate insect activity. [2] For a brief overview, see pp. 349-56 of Roff (2002). For extensive literature reviews, simulations, and so on, see Roff (1990) and Roff (1994). [3] As for the non-obvious claim of greater temporal variation as you move toward tropical areas, see Roff (1990: 405): I tested the hypothesis that habitat persistence varies with latitude with data on the rates of succession on abandoned farmland. In the northerly states of the United States (Wisconsin, New Jersey, Illinois, and New York) shrubs appear only 10-20 yr after abandonment, and even after 40 yr succession does not proceed beyond a very open woodland/parkland condition (Thomson 1943, Bard 1952, Bazzaz 1968,1975, Mellinger and McNaughton 1975, Pickett 1982), while in the more southerly states of North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia a closed canopy is formed within 15-30 yr (Billings 1938, Oosting 1942, Quarterman 1957, Nicholson and Monk 1974, 1975, Lindsay and Bratton 1980). In the Mexican tropics invasion by trees occurs within the first 2 yr, and these may reach a height of 10 m within 5 yr (Purata 1986): in the upper Rio Negro region of the Amazon Basin a loose canopy of Cecropia spp. 5 m high was formed within 22 mo (Uhl et al. 1981). Sidebar: Detroit is fortunate to be situated as far north as it is, or else the reclamation of the city by the wild would have wholly swallowed up most of the area long ago (see here too). [4] Alternatively, they could follow the lead of the elite strata of South Asia, who have managed to build a civilization despite vying with tropical Africa for status as the world's chamberpot of infectious disease. There, though, the elites have striven for centuries to isolate themselves genetically from those in lower castes, as well as to minimize their physical contact with the even more bug-bitten lower classes. References Roff, D. (1990). The evolution of flightlessness in insects. Ecological Monographs, 60(4), 389-421. -------- (1994). Habitat persistence and the evolution of wing dimorphism in insects. The American Naturalist, 144(5), 772-98. -------- (2002). Life History Evolution. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. Wolfe, N., C. Dunavan, & J. Diamond (2007). Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature, 447, 279-83. Labels: civilization, geography, pathogens, true redneck stereotypes |