|

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Over at my other blog I have a post up about inbreeding fundamentalist Mormons. When brown Muslims are hittin' it with near relations that warrants eyes averted, but if I point to slack-jawed Anglos, well, that is BoingBoing worthy. But in any case, my post focused on an older article about the prevelance of fumerase deficiency among many children within the fundamentalist Mormon community of Colorado city. But one thing struck me about the article, the top-down pro-natalist and conformist nature of the community seemed to be a perfect example of the functionalist notions of evolutionary biologists like David Sloan Wilson. He promoted the reemergence of functionalism and evolutionary analogies in sociology and anthropology in Darwin's Cathedral, the hyper-fecund & genetically inbred fundamentalist Mormons are an ideal case of a group level super-organism, but just like a putative lineage of human clones who reproduce parthenogenetically they are clearly doomed. I suspect that functionalism isn't totally bunk, but like socialism it looks better on paper than it is in practice, really successful long term societies are more decentralized, flexible and fluid.

Human Lineage-Specific Amplification, Selection, and Neuronal Expression of DUF1220 Domains

posted by

Razib @ 8/31/2006 10:34:00 PM

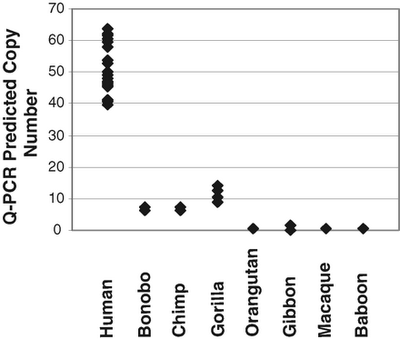

Human Lineage-Specific Amplification, Selection, and Neuronal Expression of DUF1220 Domains:

From the conclusion:

John Hawks has more. 98% sequence identity with a chimp? Yeah, but we're all human where it counts baby (no mention of sperm or testes in the paper). Figure below the fold.

Against The Politically Incorrect Guide to Darwinism and Intelligent Design

posted by

Razib @ 8/31/2006 10:29:00 PM

As someone who makes no bones about being against politically correct evolutionary biology, I will take up RPM's call to link to Panda's Thumb's chapter-by-chapter rebuttal of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Darwinism and Intelligent Design. They fight Creationism so I don't have too!

Some encouraging gene therapy news in Science:

According to reports in Swedish media (i.e. Dagens Nyheter) two late-stage terminal patients out of 17 trial subjects were cancer free after 18 months. UPDATE: Here is the flood of Google News articles.

Human bodies maintain an optimal environment for cellular function. Cold-blooded animals function sluggishly when cold. I've wondered how bacteria manage to function at different temperatures. I'd assumed that bacteria are highly adapted to either high or low temperatures and that homeostatic feedback maintains biological systems in a viable range over modest daily temperature changes. But what happens when their environment rapidly changes? Does that bacterial line die out? Perhaps not.

Bacteria beat the heat "A general rule for enzyme reactions states that as the heat rises, so does the reaction rate. Contrary to this rule, and the scientist's expectations, both reaction rates peaked at a certain point, and remained steady thereafter. For each enzyme, the peak occurred in the bacteria's 'comfort zone.' Further comparisons of the enzymes, which were nearly identical, turned up differences in just two of the hundreds of amino acids making up the enzyme sequence. When the scientists replaced these two amino acids in the enzyme adapted to the moderate temperatures with those of the heat-loving enzyme, they observed an increase of about 10 degrees in the average temperature at which the reaction rate peaked. Scherz: 'This study shows that enzyme efficiency is tuned to the average temperature of the bacterial habitat, rather than the immediate conditions. This may protect the cells from harmful swings in enzyme activity' " In this experiment, changing two amino acids in an enzyme changed the temperature of peak reaction rate. The bacteria colony could adapt to new temperatures with just a few mutations. Life has evolved to adapt rapidly to changing environments. Lifeforms that couldn't adapt went extinct.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

A few weeks ago I watched the Robert Wright Ann Althouse diavlog. One thing that struck me was that in the beginning they addressed Althouse's political ideology (i.e., was she a libertarian?). Althouse offered that she considered herself an independent, who voted for Feingold and Bush in 2004, splitting her ticket. Up until that time she has uniformly voted Democrat. She observed that her own experience is that when she did not toe the right-wing line she was ignored, but when she agreed with the Right they praised her. In contrast, the Left ignored her because of their disagreemants on several issues. The general opinion was that the Left shunned heretics and the Right sought converts. Interestingly, Wright spent the rest of the diavlog being surprised when Althouse expressed liberal views on particular topics, and even hopefully mooted the possibility that she could "come back" to "their side." This, throughout an interview where she had expressed a host of different views, some on Wright's "side," and also offered that historically she tended to vote Democrat. Watch the whole thing, and this is not meant as a criticism (I don't really create except as a data point in favor of what Althouse has referred to), but Wright seemed to exemplify exactly the tribalist purity which Althouse claimed was a problem on the Left, ignoring their commonality.

Anyway, I don't comment much on politics on this blog because I have nothing to say, but I was pretty shocked that Wright behaved in such a manner even after addressing this tendency with Althouse.

In the wake of the British National Health Service denying IVF treatments to very obese women Big Fat Blog says:

No comment. (via Dr. Joan Bushwell's Chimpanzee Refuge)

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

The New York Times has an article about a Malay woman who converted to Christianity and now wishes to marry her fiance, who is also a Christian. Her problem is the ideology promoted by the Malaysian government that by definition Malays are Muslim. Additionally, Islamic tradition reinforced by shariah imposes strong sanction, up to capital punishment, upon those who apostatize from the faith. The day to day reality of apostacy varies, there are many unbelievers within the Muslim world, but their rejection of religion is not public and they do not generally follow another religion. The woman profiled in the article not only rejected Islam, but, she converted to another religion and is making her conversion public knowledge and attempting to assert her rights to conversion through the legal system. "Moderate" Muslim nations like Malaysia are in a twilight zone, attempting to reconcile the medieval center of gravity of world normative Islam with their own acknowledgement that the "next stage" in national development requires a relaxation of the coupling between traditional norms and state sanction. The power and strength of Christianity, in particular evangelical Christianity, in concert with the the suffocating march of international liberalism is that it will confront a large number of Muslims and force them to turn away from the older norms of exclusion, domination and anti-individualism (radical Protestants also played this role in northern Europe). One of the advocates for the woman in question is himself a Muslim; in nearby Indonesia it is not unknown for nominal believers in places like East Java to transfer their religious identification to Christianity or Hinduism. A similar process of religious competition occurs in much of Africa as Muslims become Christians and Christians become Muslim. But, the unfortunate reality is that the "center" of the Muslim world, Saudi Arabia and the Arab world, represent the other antipode of fluid toleration of freedom in regards to choice of religion. For the world of Islam these are the Edgardo Mortara moments, but the outcome will not be measured via such sensational cases, but rather by the slow but inevitable wheels of liberalism grinding away at the edifice of medieval social control.

Monday, August 28, 2006

A. W. F. (Anthony) Edwards is one of Britain's most distinguished geneticists. He studied genetics at Cambridge as one of the last students of R. A. Fisher, and like Fisher he has contributed actively to both genetics and statistics. In genetics his work includes several influential papers on the reconstruction of phylogenies, and a widely-read recent article on 'Lewontin's Fallacy'. In statistics he is known especially for his development and advocacy of the concept of Likelihood as a criterion for scientific inference. He has also made a notable contribution to combinatorial mathematics by finding a method of constructing Venn diagrams for any number of sets. In addition to many scientific papers, he has written four books: Likelihood (1972; expanded edition 1992); Foundations of Mathematical Genetics (1977; 2nd edition 2000); Pascal's Arithmetical Triangle: the Story of a Mathematical Idea (1987; expanded edition 2002); and Cogwheels of the Mind: the Story of Venn Diagrams (2004). He has written extensively on the history of genetics, mathematics, and statistics, and has co-edited (with H. A. David) Annotated Readings in the History of Statistics (2001), and (with Milo Keynes and Robert Peel) A Century of Mendelism in Human Genetics (2004). He is also a champion glider pilot. A. W. F. (Anthony) Edwards is one of Britain's most distinguished geneticists. He studied genetics at Cambridge as one of the last students of R. A. Fisher, and like Fisher he has contributed actively to both genetics and statistics. In genetics his work includes several influential papers on the reconstruction of phylogenies, and a widely-read recent article on 'Lewontin's Fallacy'. In statistics he is known especially for his development and advocacy of the concept of Likelihood as a criterion for scientific inference. He has also made a notable contribution to combinatorial mathematics by finding a method of constructing Venn diagrams for any number of sets. In addition to many scientific papers, he has written four books: Likelihood (1972; expanded edition 1992); Foundations of Mathematical Genetics (1977; 2nd edition 2000); Pascal's Arithmetical Triangle: the Story of a Mathematical Idea (1987; expanded edition 2002); and Cogwheels of the Mind: the Story of Venn Diagrams (2004). He has written extensively on the history of genetics, mathematics, and statistics, and has co-edited (with H. A. David) Annotated Readings in the History of Statistics (2001), and (with Milo Keynes and Robert Peel) A Century of Mendelism in Human Genetics (2004). He is also a champion glider pilot.To see his replies to our 10 Questions, click on "Read full post". 1. You were among the last students of R. A. Fisher. Can you share with us some reminiscences of him? I first met Fisher in the summer of 1956 and had much contact with him until his death six years later. I saw him last during the Second Human Genetics Conference in Rome in 1961 and subsequently corresponded with him. I have published quite a few of my reminiscences of those times in a number of different places. I have been fortunate in having had a lot of contact with the older generation who knew him better than I did - people like Barnard, Bartlett, Finney, Yates, Race, Ruth Sanger and Bennett - and with members of his family, especially Rose, Harry and Joan (his biographer) amongst his children. Being a fellow of the same Cambridge college (Caius) as Fisher, though not at the same time, has meant daily contact with people who knew him well. But the most important thing is his science, and there everyone can get to know him through his writings, which reveal a mind of extraordinary power and vigour. That is the Fisher whom succeeding generations should learn about and admire. 2. Like Fisher you have worked in both statistics and genetics. How do you see the relationship between them, both in your own work and more generally? In a sense I have benefitted from being an amateur in both fields so that I see no boundary between them. Though I qualified in genetics the subject almost immediately changed so radically through advances in molecular biology that most geneticists would not now regard me as one of themselves anyway. My generation thought genetics was the study of inheritance; theirs thinks it is the study of genes. As to statistics, I attended eight lectures by Henry Daniels in Cambridge but am otherwise self-taught, being hugely influenced by Fisher's book Statistical Methods for Research Workers which he told me to buy (and then signed for me). Genetical statistics has changed fundamentally too: our problem was the paucity of data, especially for man, leading to an emphasis on elucidating correct principles of statistical inference. Modern practitioners have too much data and are engaged in a theory-free reduction of it under the neologism 'bioinformatics'. We had to navigate by the stars; they have GPSs. 3. Much of your early work (some of it in collaboration with L. L. Cavalli-Sforza) was on methods of inferring phylogenies. How do you assess the progress in this field since the 1960s, and how have your own methods stood up to empirical tests? All my work was in collaboration with Luca Cavalli-Sforza. It was his idea. He hired me to join his group in Pavia in Italy, not specifically to work on phylogenies but to apply the new-fangled computers to human genetics generally. The late delivery of the Olivetti computer was a blessing in disguise because it left us time to talk about what we would do with it when it came. I was initially sceptical because I knew that linkage was statistically difficult and here was Luca proposing what looked like linkage on a tree whose very shape also required estimating! I think progress on the theoretical side has been incredibly slow, despite the best efforts of Joe Felsenstein, the leading practitioner. In a few months in 1962 and 1963 Luca and I thought up three ways of tackling the problem: least-squares on an additive tree (his), minimum evolution or parsimony (mine) and maximum-likelihood on a stochastic model (very much a joint effort). Forty-odd years on people are still arguing about the relative merits of the descendants of our methods when all along they should have been concentrating on refining the statistical approach through maximum-likelihood, which was our real contribution. Of course, from a practical point of view the computer packages have taken over in a development parallel to that in human genetics, from shakey inferences based on too little data and doubtful logic to computer algorithms trying to digest too much. 4. Your recent article on 'Lewontin's Fallacy' criticises the claim that human geographical races have no biological meaning. As the article itself points out, it could have been written at any time in the last 30 years. So why did it take so long - and have you had any reactions from Lewontin or his supporters? I can only speak for myself as to why it took me so long. Others closer to the field will have to explain why the penny did not drop earlier, but the principal cause must be the huge gap in communication that exists between anthropology, especially social anthropology, on the one hand, and the humdrum world of population and statistical genetics on the other. When someone like Lewontin bridges the gap, bearing from genetics a message which the other side wants to hear, it spreads fast - on that side. But there was no feedback. Others might have noticed Lewontin's 1972 paper but I had stopped working in human and population genetics in 1968 on moving to Cambridge because I could not get any support (so I settled down to writing books instead). In the 1990s I began to pick up the message about only 15% of human genetic variation being between, as opposed to within, populations with its non-sequitur that classification was nigh impossible, and started asking my population-genetics colleagues where it came from. Most had not heard of it, and those that had did not know its source. I regret now that in my paper I did not acknowledge the influence of my brother John, Professor of Genetics in Oxford, because he was independently worrying over the question, inventing the phrase 'the death of phylogeny' which spurred me on. Eventually the argument turned up unchallenged in Nature and the New Scientist and I was able to locate its origin. I only started writing about it after lunch one day in Caius during which I had tried to explain the fallacy across the table to a chemist, a physicist, a physiologist and an experimental psychologist - all Fellows of the Royal Society - and found myself faltering. I like to write to clear my mind. Then I met Adam Wilkins, the editor of BioEssays, and he urged me to work my notes up into a paper. I have had no adverse reaction to it at all, but plenty of plaudits from geneticists, many of whom told me that they too had been perplexed. Perhaps the communication gap is still too large, or just possibly the point has been taken. After all, Fisher made it in 1925 in Statistical Methods which was written for biologists so it is hardly new. 5. You have written several articles about Fisher's Fundamental Theorem of Natural Selection. Following a groundbreaking reinterpretation by George Price in the early 1970s, it is now generally accepted that the theorem as intended by Fisher is valid, but some biologists would still question its practical use or importance. Can you explain in non-technical terms the meaning of the theorem, how the correct interpretation differs from earlier misunderstandings of it, and your own view on its biological importance? Oh, it's very simple. You must first recall the precise name of Fisher's book in which it is the centrepiece: The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. He is studying the mechanisms of natural selection from the point of view of populations regarded as aggregates of genes. Of course he knows, and stresses, that this is not the whole story. But to him selection's defining effect is to change gene frequencies. He sees that this will only happen if there is variability in the survival rates of different genes. Animal breeders promote artificial selection by imposing different 'fitnesses' on their stock according to desirability, breeding from some and not from others. They thus raise the mean value in the population of the character desired. Fisher saw that this process implicitly relies on a correlation between the character and fitness, so that progress will depend both on the magnitude of this correlation and the extent to which the character is genetically determined. What happens, he then asked, if we designate fitness itself as the character, making the correlation perfect? The answer is that the mean fitness of the genes will increase by an amount that depends on the extent to which fitness is determined by them. This is the fundamental theorem (in a modern paraphrase): 'The rate of increase in the mean fitness ascribable to natural selection acting through changes in gene frequencies is equal to the additive genetic variance in fitness'. The theorem does not involve the mean genotypic fitness - that is, the weighted mean of the fitnesses of the genotypes - which is where most interpreters of it went wrong. Fisher's repeated denials that his theorem referred to the mean genotypic fitness, itself immortalised in Sewall Wright's 'adaptive landscapes', went unheeded. In 1941 Fisher even published an example in which gene frequencies were changed under natural selection but the mean genotypic fitness stayed constant. Nobody noticed. The brilliance of the fundamental theorem is not merely that it expresses the central dogma of natural selection - the connection between genetic variability and selective change - but that it does so exactly. Fisher discovered what the rate of change was proportional to: not to the total variance in fitness of the genotypes but only to that part of it found by fitting a weighted linear regression to the genotypic fitnesses. This is the part accounted for by the regression itself, the so-called additive genetic variance. Animal breeders know it as the variance of the breeding values of the genotypes. The fundamental theorem disregards the way the genes are distributed through the population, which will depend on the amount of heterosis in fitness, the extent of assortative mating, and similar possibly transient effects. What matters to it are the changes to the mean fitness brought about by changing gene frequencies. This, then, is the theorem whose 'practical use or importance' 'some biologists would still question'. Let them ask the animal breeders if it is any 'use', and let them ask themselves whether they think Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection is of any 'importance'. If they do, then the fundamental theorem should help them to a deeper, Mendelian, understanding of it. If, however, they hanker after a theory that can make evolutionary predictions, like Wright's adaptive landscapes were thought to do at one time, they are crying for the moon. Possession of the fundamental theorem will no more enable you to predict the flow of evolution than possession of Newton's law of gravitation will enable you to predict the time of high tide at London Bridge. It should not be forgotten, however, that shorn of its genetical complexities the theorem does have predictive power, just as the law of gravitation does when applied to the celestial movements that underlie the tides. 'In a subdivided population the rate of change of the overall growth-rate is proportional to the variance in growth rates'. The 'populations' could be economic sectors, for example, or even one's own savings accounts. 6. Your career since the 1950s spans the period in which computers, and off-the-shelf programs, have become widely available. Has this been an unmixed blessing, and do you think the development of statistics or genetics would have been very different if computers had been available in, say, 1900? A mixed blessing of course, because the existence of programs hinders the development of the underlying theory. This is particularly true in statistics where, despite assertions to the contrary by Bayesians, the underlying theory is still a matter for discussion. The phenomenon can be seen in the field of phylogenetic trees, where programs based on different methods proliferate. 1900 is a peculiarly well-chosen date on which to hang the question. Not only was it the year in which Mendel's results became widely known but it was also the year of the publication of the second edition of Karl Pearson's The Grammar of Science, which included chapters on biological science for the first time. The Grammar of Science was hugely influential in its day, proclaiming that the function of science was 'not to explain, but to describe by conceptual shorthand our perceptual experience'. 'The man who classifies facts of any kind whatever, who sees their mutual relation and describes their sequences, is applying the scientific method'. The computer implementation of this sterile philosophy would have had a devastating effect, particularly on the development of statistical theory and the acceptance of Mendelism. All Pearson's formidable energy would have been devoted to amassing vast quantities of information to be sifted for correlations. William Bateson's 1894 six-hundred-page Materials for the Study of Variation treated with especial regard to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species would have been digitally scanned and computer programmers urged to uncover its secrets. It doesn't bear thinking about! 7. In statistics you are especially known for developing and advocating the concept of Likelihood and its use in scientific inference. Can you explain how Likelihood differs from probability, and why Likelihood methods are useful in evaluating hypotheses? Likelihood compares statistical hypotheses; it has nothing to say about a hypothesis on its own, like a test of significance does. Imagine two statistical hypotheses, each of which predicts the probabilities of all the possible outcomes of an experiment - which need be no more complex than tossing a biassed coin a number of times and counting the heads. The experiment is performed, the heads counted. Given this count, was the probability of heads p1 (the first hypothesis) or p2 (the second hypothesis)? Now imagine doing the experiment lots of times assuming the first, and then the second, hypothesis. Would you not prefer the hypothesis that had the shorter expected waiting time until the exact number of heads observed turned up? If so, you have just chosen the one with the greater likelihood. The likelihood of a hypothesis is proportional to the probability of the data given the hypothesis. Meaningless for a hypothesis by itself because of the undefined constant of proportionality, with two hypotheses to be compared on the same data this constant is irrelevant, and the ratio of their likelihoods (or the difference in their log-likelihoods) becomes a measure of the support for one hypothesis versus the other. Likelihoods therefore derive from probabilities, but unlike the latter are not additive. Whereas you can sum the probabilities of two possible outcomes of an experiment to form the probability of 'either one or the other', you cannot do the same for the likelihood of two hypotheses; 'either one hypothesis or the other' is not in itself a hypothesis enabling the probabilities of outcomes to be computed, so no likelihood for it is defined. But you can graph the likelihood as a function of p and pay special attention to its maximum, the maximum-likelihood estimate of the probability of heads. The concept of the likelihood function is fundamental to all approaches to statistical inference, whether Bayesian, Neyman-Pearson, or Fisherian. Not everyone agrees that it is meaningful standing alone by itself, but I (and others before me) believe it is. Doubters can always fall back on the above 'how long to wait' argument, which I think was due to David Sprott. 8. You have written extensively on the history of genetics, statistics, and mathematics. Apart from the intrinsic interest of historical studies, how important do you think a knowledge of the history of science is for practising scientists? I find it essential, and cannot imagine doing science without it. Much of what counts as science nowadays is rather theory-free. We don't really have a word for it. Sequencing the human genome, for example, is a marvellous achievement relying on technical advances of great ingenuity but it did not require historical understanding. It differs intellectually from, say, the associated activity of trying to estimate linkage values between gene loci. The history of the latter, on which I have written recently, is an essential part of the study of the problem, and much modern work suffers from its neglect. Celebrating the centenary of the publication of the Origin of Species in 1959, Fisher said: More attention to the History of Science is needed, as much by scientists as by historians, and especially by biologists, and this should mean a deliberate attempt to understand the thoughts of the great masters of the past, to see in what circumstances or intellectual milieu their ideas were formed, where they took the wrong turning or stopped short on the right track. I agree. 9. R. A. Fisher was a keen eugenist. What are your own views on the role (if any) of eugenics in the modern world? Fisher's world was so different from ours, in three ways in particular. Then (say the period between the wars) nation-states were much more independent of each other so that it was possible to discuss population matters for Britain in relative isolation; secondly, it was a time of concern about the possibility of a declining home population; and thirdly many scientists were in the first flush of enthusiasm for the application of Mendelian principles - so recently elucidated - to man. None of this is true today. For myself, though I was once a grateful holder of a Darwin Research Fellowship of the Eugenics Society (now the Galton Institute), since boyhood I have been more concerned about the quantity of people on earth rather than their quality. In the early 1960s I was a founder-member of a body called, I think, the Conservation Society, which does not seem to exist today. Its main platform was that too large a population would be unsustainable. At the time there was much discussion about over-population which was seen as one of the greatest dangers facing mankind. Interestingly, the worse the problem gets, the less it is discussed. Yet the mounting dangers we face, such as the possibility of global warming, are all exacerbated by too high a world population, given its enthusiasm for motor-cars, aeroplanes, and environmentally-damaging activity generally. It seems that people fear the charge of racism if they comment on population growth - they intuitively understand Fisher's fundamental theorem. 10. Like yourself, your brother, J. H. Edwards, is also a distinguished geneticist. Nature, nurture, or sibling rivalry? Well, certainly not sibling rivalry. It is true that we have been sufficiently alike at some stages of our lives to have been mistaken for each other. At the Rome Conference of Human Genetics in 1961 we were in a lift with the Swedish geneticist Jan Lindsten when he engagingly introduced us to another participant as 'the two most confused brothers in genetics'. In fact I am 7 1/2 years younger than John, and due to mother's illness, father's war service, and wartime privations generally, I hardly encountered him until the end of the war when I was ten. We developed boyhood enthusiasms for science quite independently, he for biology, me for astronomy. But there was a common factor in our education from thirteen to eighteen. We both attended Uppingham School, though of course not at the same time, and were exceptionally well-taught in science and mathematics, in some cases by the same teachers. I cannot stress this influence too strongly. Since I only went to Uppingham because my elder brother did, is that nature or nurture? Subsequently John's main influence was when I was learning about likelihood (see the preface to my book Likelihood). He, being medically qualified, keeps me straight on medical matters and I try to keep him straight on things statistical. I deliberately stayed off linkage theory so as not to get too close to his interests. John was more influenced by Lancelot Hogben and J. B. S. Haldane than I was. There is a wonderful letter from Fisher to R. R. Race in 1960 in which he refers to me as 'my Edwards from Cambridge' and to John as 'only one of Hogben's [pupils]', so at least Fisher got us straight. And John introduced me to gliding. Though not exactly a 'champion', to use your word, I have enjoyed fifty years gliding and hope for a few more yet. Labels: 10 questions

Within my brain, foun-tains over rugged moun-tains of my terrain, diggit I came too far to front. So I'm meditatin on how to maintain. Stepped off at City Hall into the rain... - Black Thought

That ain't a igloo, that's my watch. And that ain't snow, baby that's my chain. That's not an ice tray, that's my teeth. And that's not a snowcone, that's my ring. - Paul Wall Two very important papers came out yesterday in Science. One (from the Bear Lab at Picower) demonstrates that inhibitory avoidance learning can induce LTP (long-term potentiation) in the hippocampus, and the other (from the Sacktor and Fenton labs at SUNY-Downstate) demonstrates that a particular variant of Protein Kinase C (PKC) known as PKM-zeta (that is necessary and sufficient for LTP maintenance) is necessary in the hippocampus for long-term maintenance of a spatial avoidance memory. Together, these papers make one much more confident about making predictions about the cellular mechanisms of memory based on electrophyz studies in the hippocampal slice. The Scientist has a nice summary of these two, and I suggest reading it. I think the two papers could be even further integrated by taking into account a recent discovery by the Malinow group concerning PKC's role in AMPA receptor trafficking. By the way, as I get deeper into this post I realize that it is going to make no sense if you don't understand at least the basics of neurotransmission, so if you aren't comfortable with that try a little of this before you read on. Update:From Todd Sacktor in the comments: ZIP is quite specific to reversing late-LTP. We showed in Serrano et al. and Frey's lab showed in Sajikumar et al. (both in J. Neuroscience) that it did not affect baseline synaptic transmission or reverse early LTP. We are currently looking at other types of behavioral memory (including the inhibitory avoidance used in the Bear study). If all that above seemed like an alien language, just give me a second and I'll unpack it. First off, the behavioral paradigms. Inhibitory avoidance is sometimes known as passive avoidance. All the rat has to do to avoid a shock is to sit still, but the rat is placed on an inch-high platform in the light and the shock grid is in a dark area of the chamber. Rats would much rather be in this dark area, so they have a tendency to step down. The first time they do this, they get a mild foot-shock. Learning is measured by how long it takes them to step down a second time, but this paradigm is so widely used and consistent that we can assume the rat learned the association without even bothering with a test trial. It is not entirely clear just what it is that rats learn during inhibitory avoidance training. It seems that they should be learning an association between the stepping behavior and the shock. On the other hand, inhibitory avoidance could just be a fancy version of contextual fear conditioning (CFC). In CFC rats are simply placed in a box, given a little time to explore, and then administered foot-shock. The indication of learning is a stereotyped behavior known as freezing when they are placed in the same context. This is an adaptive response to fear for rats at least in part because predators (like hawks and whatnot) have poor foveal vision, so they do a lot better if they have a moving target. Point is, rats stand still when they are scared. So it is not clear in inhibitory avoidance whether rats are scared of the step down or are more generally afraid of the apparatus leading to freezing. The reason I'm bothering to make all this distinction is that the association between a cue and a shock has been traced to the amygdala rather than the hippocampus. The hippocampus is thought to encode the context by binding its features up as a single index cue that can be associated with shock in the amygdala. It is possible that the hippocampus constantly takes snapshots of the various aspects of the context together and that stringing these together makes up the film of vivid episodic memory that some refer to as 'mental time travel'. This makes it curious that the LTP-like changes in the Bear Lab paper are found in the hippocampus when there are "walk-through" controls that get all the same contextual/episodic information except for the shock. My tentative take is that trained and control animals both encode the contextual information, but that shock provides a modulatory input that says, "hey, why don't you go ahead and lay the memory of this context down a little more permanently.. i have a feeling it's going to be important later.." This sort of input could come from the amygdala. In the PKM-zeta study, the behavioral paradigm is Active Spatial Avoidance. The rats are placed on a slowly spinning circle. One portion of space is declared the "shock zone" and remains stationary while the rest of the world spins, so the rat has to keep moving to keep from being eventually moving into the shock zone due to the platform's rotation. It's like being a vampire who has to remain outdoors and near the equator. This task could again be separated into two separate types of learning. The rat needs to encode the overall spatial scheme, which is something we expect the hippocampus to be good at, and it has to associate a particular portion of the map with shock. It should be noted that use of this behavioral paradigm is not nearly so widespread as inhibitory avoidance, so less is known about the neural substrates, but the hippocampus appears to be involved. A good way to parse the various forms of learning necessary for the task would be to allow the animal access to the spatial environment without the shock reinforcer, so it can learn the spatial information first. You might expect a more rapid acquisition curve once the shock is turned on, and this improved acquisition might be affected by hippocampal manipulations. The drug manipulations in this study were in the hippocampus, and they knocked the memory out, so something that the rat needs to know to perform this task is encoded in the hippocampus. I'm just not sure if it is a cognitive map or some "episodic" memory like "Remember that time when i was in this spatial area and I got shocked? I better get outta here." One is remembering a space and one is remembering what happened in a space. Now let's take it down a level or two. What is LTP? It is a model for memory at the cellular/synaptic level. A long time ago, Donald Hebb suggested that information in the nervous system was probably stored as changes in the synaptic connection between neurons. In particular, he suggested that they synaptic strength or weight would be increased when the pre-synaptic neuron and the post-synaptic neuron fired coincidentally. I dunno if it was Hebb who came up with the paraphrase, but everyone paraphrases this principle as "Cells that fire together wire together." In 1973, Bliss and Lomo were able to demonstrate a cellular phenomenon that did just what Hebb has imagined. They found that high-frequency stimulation of a set of synapses led to enhanced strength. The strength is ascertained by giving baseline pulses of fairly weak stimulation and measuring the post-synaptic change in electrical potential. After high-frequency (tetanic) stimulation, the electrical response to baseline stimulation is potentiated. The emerging consensus is that synaptic strength is determined by the amount of ion flow through AMPA-type glutamate receptors in response to pre-synaptic glutamate release. Thus, you could enhance synaptic strength either by making existing AMPA receptors more permeable or by putting more AMPA receptors in the synapse. This latter is known as AMPAR trafficking. Modifications to AMPA receptors accompany LTP induction and memory acquisition. In particular, one portion of the AMPA receptor (the c-terminal tail of the GluR1 subunit) has a bunch of little spots on it where it can be accessorized. It's like, does Paul Wall really wanna roll out with his neck, wrist, and grill iced up tonite or is he far from home and might get his chain snatched if he comes too flashy? Then he might only wanna display his Balla Status with his neckpiece. Three of these spots (S818, S831, and S845) are partially understood. The general idea is that more accesories = stronger synapses. S831 can be modified by CaMKII and PKC, but this doesn't seem to be sufficient to drive trafficking. S845 is modified by PKA, but this isn't enough either. In fact, it seems more like the S831 modification controls ion flow (channel conductance) more than it does trafficking. The Malinow group at Cold Spring Harbor just reported a month ago now that they had characterized S818. S818 is modified by only by PKC isoforms. There are several versions of PKC (11, I think), and they have special expression patterns and activation requirements. S818 is in a part of the AMPA receptor that is close to the cellular membrane and is packed full of positive charges. The membrane is made of lipids and may have trouble playing with charged molecules. PKC adds a bunch of negative charge to S818 and helps neutralize the membrane-proximal region of the AMPA receptor allowing the AMPA receptor to fuse into the membrane and start contributing to synaptic strength. So PKC-mediated phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors may be a central mechanism in enhancement of synaptic strength (LTP). This was not known until a month and a half ago which explains why the Bear lab only checked on the status of S831 and S845 after inhibitory avoidance training. The Bear lab attempted to show that learning induces LTP with four results: 1) After training, S831 is modified the same way it is after LTP. 2) After training, there are more AMPA receptor subunits in or near synapses. 3) After training, baseline stimulation of the synapses produces greater post-synaptic potentials. 4) Synapses that show this enhancement are harder to potentiate with high-frequency stimulation (i.e. the normal way you induce LTP). The third and fourth are really the money. They were made possible by the use of multielectrode recording arrays. Learning doesn't just globally increase synaptic weights. That would be silly. The changes have to be fairly synapse-specific. So if you just stuck one recording electrode in the hippocampus you might miss the change. Bear and co were able to monitor the status of several recording sites at once. After training, some small portion of synapses were enhanced, while the others seemed to drop off slightly. This drop off is really interesting to me because it looks a lot like some sort of homeostatic signal that might keep overall excitability in the right range for a good signal-to-noise ratio. That's the problem with just using LTP in your model. Eventually you would get everything strengthened to the max, and you couldn't tell one piece of data from the other. The paper is more bland and probably more reasonable. "We interpret the coherent decreases in fEPSP slope as reflecting changes in the behavioral state of the animals over the duration of the recording experiments." There is one little disconnect in these observations though. The AMPA receptor changes are fairly short-lived. They are up a half-hour after training, but back down after 1-2 hours. The synaptic strength changes, on the other hand, can last over 3 hours, and we know that the memories last much longer than even that. The authors suggest that only a few of the initially enhanced synapses actually stick it out and contribute to the long-lasting potentiation. This would drop the number of synapses displaying the AMPAR-related biochemical markers so far down that the assays just aren't sensitive enough to detect them anymore. Perhaps another issue is that in order to detect the changes in amount of synaptic AMPA receptors they normalize to actin levels. I haven't had anyone explain to me yet why you would expect actin levels to remain constant during synaptic modification. Go back and read here and here. Actin is a cytoskeletal protein that is associated with dendritic spine morphology and is dynamically regulated in response to LTP induction. One could easily imagine an initial burst of AMPA receptor insertion followed by changes in the actin cytoskeleton to produce larger synapses and accomodate the new strength setpoint. The drop off of the AMPA receptor signal back to baseline could really reflect a slower rise in synaptic actin. Also, there is another potentiality that can't explain the overall levels data but could explain the rapid fall off of the S831 modification. The S831 modification may be a simple, fast response to do the trick of enhancing synaptic responses quickly while the slower-reacting process of AMPAR insertion is taking place. S831 modification, remember, allows more ion flow, but doesn't seem to affect receptor insertion. I could see S831 doing its duty to begin with, but then handing off responsibility to a more permanent change effected by S818 modification and an increase in total number of receptors in the synapse. So the mechanism of synaptic strength enhancement would evolve over its lifespan. There would be mechanisms for acquisition that were separate from those involved in maintenance. Maintenance. What a memory does day-to-day when you aren't recalling it or forgetting it. All those phone numbers you know are sitting there as configurations of synaptic weights that have to stay at the right weight as they receive noisy input and all the consituent synaptic molecules are degraded and replaced. The Sacktor lab has made a very nice case for a special role for PKM-zeta in memory maintenance. PKM-zeta is an atypical isoform of Protein Kinase C. Most PKC's are activated in response to increases in intracellular signaling molecules (such as calcium and diacylglycerol (DAG)), but PKM-zeta doesn't need any of that. It just goes. You make PKM-zeta and it starts doing its job. It is thus referred to as a constitutively active protein kinase. PKM-zeta isn't required for LTP induction. It is required for LTP maintenance. In fact, just washing PKM-zeta onto a hippocampal slice will cause increases in synaptic strength. This increase is probably due to increased AMPA receptor insertion. Sacktor and co have a molecule called Zeta Inhibitor Peptide (ZIP) that specifically inhibits PKM-zeta and no other PKCs or other kinases. They showed that ZIP can return potentiated synapses to baseline even after they have been potentiated for 22 hours. So we've got a drug that specifically affects LTP maintenance and we think LTP = memory, so let's put the drug in and see if it affects memory. Sho' nuff. If you drop ZIP into the hippocampus 22 hours after active spatial avoidance training the animal drops back down to pretraining peformance levels. It forgets everything. This isn't a temporary retrieval impairment. The memory is still gone a week later. That, my friends, is money. Some eternal sunshine type isht. The whole hippocampus isn't messed up cos the rats can acquire new memories even under the influence of the drug. It only screws up fairly new memories that have been stored. There are a couple of things to note about this discovery. The manipulation is still effective on month-old memories. If you've read any accounts of memory research you will be familiar with the case of H.M. He is commonly used to illustrate the principle of systems consolidation. Some people believe that the hippocampus is only a temporary memory storage site and that (maybe during sleep) it trains up other permanent storage sites in the neocortex. For instance, H.M. basically had his hippocampus removed, and he still seemed good at remembering stuff from his childhood (which was presumably consolidated) but wasn't so hot at memories acquired shortly before his surgery. People have extended this observation to rats and showed that lesioning the hippocampus has less effect on month-old memories than on day-old memories. This whole area is very controversial though and there is growing support for the notion that the hippocampus never stops playing a role. This set of experiments speaks to the issue of systems consolidation by showing that month-old memories are abolished by a drug manipulation targeted only to the hippocampus. There are caveats and complexities, but it certainly looks on the surface like synaptic changes in the hippocampus are still housing the memory. But this brings me to my other point. What is really happening when they drop ZIP into the hippocampus? Is every synaptic weight getting dropped down to its lowest possible setting? Do the rats forget everything that the hippocampal memory system was responsible for? There are control experiments where ZIP is shown not to affect baseline synaptic responses, but why shouldn't it? It seems like the rats should have some information stored in their hippocampi already. Surely some of the weights are already set at high levels. Why wouldn't ZIP knock those off? I'll get back to you when I figure all that out. Perhaps memories really are consolidated, but it just takes longer than a month. That doesn't mean they have to leave the hippocampus, but perhaps the maintenance mechanism changes such that it isn't reliant on PKM-zeta activity anymore. I don't know if the anyone but the Malinow lab is capable of assaying the state of S818, but I think it would be really interesting to take a look at the correspondence between PKM-zeta levels and S818 status. You could directly control the weight of a given synapse by modulating the local amount of PKM-zeta to determine what percentage of newly generated AMPA receptor subunits get modified at S818 and inserted into synapses. I should say that I am not implying that PKM-zeta is the only determinant of synaptic strength. One should be skeptical about 'magic bullet' hypotheses. No single molecule is going to do the trick. Also, while these studies make a strong case that LTP may be more than just a model of memory, the link still is not complete until we can perform an engineering feat using the theory. Can we actually implant a memory in an animal by inducing LTP at the proper synapses? From a 2003 paper by Richard Morris (that you can download for free if you want): The fourth criterion, surely not yet met, is mimicry: were it feasible to alter the pattern of synaptic weights in a network in an appropriate manner, the animal should behave as if it remembered something that, in practice, had not happened. Tim Bliss calls this the 'Marilyn Monroe' criterion. This weakness of the available data apart, a rich array of physiological, pharmacological, molecular engineering and other techniques, allied to behavioural studies, have now tightened up the link between activity-dependent synaptic plasticity and memory to a point where it is reasonable to set aside a scientist's natural scepticism about the central principle.

I just finished Carl Zimmer's excellent book At the Water's Edge, a general audience recounting of two major events in macroevolution--the evolution of tetrapods and of whales. One of the major recurring themes is how past events in evolution constrain the probability space of the future. This passage (in a section describing Hox genes and limb development) stopped me cold:

My two thoughts/questions: 1. One-third of the individuals in this small population had dramatic variation in their limbs (bone fusions, extra bones). That's a lot. Does anyone know of numbers like this for humans? Are we as polymorphic as this in terms of structure? 2. The fact that all these mutations occured along the branching limb axis set essentually by Hox genes is striking, and emphasizes the role of development in determining natural variation (ok, yeah, evo-devo people have been saying this for years. duly noted). Have these sorts of results been found in other organs (like say, the brain)? I think this is going on my list of books to read.

Today's science column by Anjana Ahuja in the London Times, available online here, has a couple of stories.

First, she describes a new book by linguist Charles Yang about the acquisition of language. Yang apparently argues that babies are born with an extensive set of innate grammatical capacities - sufficient to cover all the world's languages - most of which are then discarded or suppressed as the baby learns the specific grammar of its own 'mother tongue'. It's difficult to tell just from this description how Yang's theory differs from those of Chomsky or Pinker, but it sounds like he hypothesises a much richer innate repertoire of grammar than they do. I have no idea how this stands up to the evidence, but I can't help thinking it sounds very inefficient in evolutionary terms. Wouldn't one expect a relatively simple and general language capacity to evolve first, and then specific languages to evolve (culturally) to be consistent with the general innate capacity? Whereas Yang seems to envisage an elaborate evolved capacity, much of which is never used in any single culture. But the book sounds like one to add to the reading list - eventually! The second report is about the Hobbit controversy. The point to note is that there is a further paper forthcoming in the Journal of Human Evolution, which defends the Hobbit as a distinct species. No doubt Dienekes, John Hawks and others will comment in due course. Nothing much to do with genes, but while looking up the online edition of the Times to find Ahuja's article I came across the following 'breaking news' item, here, the text of a remarkable letter by the Austrian girl who was kidnapped and held captive in a basement for 8 years. If it is really all her own work, it shows an astonishing intelligence and maturity in the circumstances.

The LA Times just ran two article about genetic engineering (here and here). I can't guarantee that these articles are free of "idiotic mistakes" of the kind that drive Greg Cochran nuts, but I thought they were interesting. A money quote:

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Here is a portion of an email I received from an occasional correspondent:

The comment is not India-specific. Many of my friends with little or no science background are poorer for it. They make grand generalizations about human "nature" with pretty much zero understanding of the biological constraints, and psychological propensities, of our species. And yet, in my experience many scientists are utterly clueless outside of their own field of expertise. Many "old timers" on this blog will remember David Deutsch getting schooled by godless capitalist in regards to evolution and genetics. In a broader sense, if scientists stuck to talking about their particular set of questions that would be fine, but their attempts to discuss history or international politics in my opinion are often as nuanced or informed as Post Modernists who use the gloss of mathematical terminology in their hucksterism. And yet the demands of the modern world mean that there are few Leibniz's, and it seems unlikely that anyone could be a Leibniz. Even within fields like "biology" and "chemistry" there are clans which never meet and speak in mutually unintelligible dialects. Ironically, though today we often (at least among the elites) deny the importance of a "canon," it maybe that a canon is even more important in providing common points of reference as our professional interests become more specialized. Analogies and metaphors are laced throughout our speech, conversation and dialogue, and yet they rely on some level of common knowledge and deep understanding of the conceptual structures which characterize a particular idea or system. To some extent the canon does not matter in regards to content. I think the substance does have utility in other ways, e.g. a knowledge of American history, and the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, might be beneficial to Americans, especially the elites, in the way they approach their responsibilities as a citizen. But, the important point is to facilitate smooth communication. Of course, we all have pop culture. We all know Real World and Nelly. That's a common lexicon. But is this sufficient? Is the idea that we should know Great Books simple snobbishness? Does watching Real World allows us to generate templates of the "Angry Black Guy" (e.g., Kevin from New York I, etc.) or "Rural Virgin" (I forget) which aid in getting across our points?

Saturday, August 26, 2006

The New Yorker has an interesting piece up about the characters involved in the Poincare Conjecture. I have to say, Grigori Perelman seems out of central casting for Simon Baron-Cohen. And the behavior of the Chinese mathematicians is remiscient of some of the problems pointed out by Richard Nisbett in The Geography of Thought in regards to the development of a science-for-science's-sake culture in East Asian cultures.

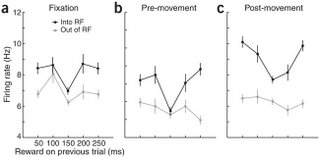

I just finished reading Decisions, Uncertainty, and the Brain: The Science of Neuroeconomics by Paul Glimcher though, and I would recommend it to a friend. The book is about 5 years old now, and neuroeconomics is kinda blowin' up. Glimcher believes that neuroscience has been dominated by a paradigm based on finding the minimal neural circuitry necessary to produce stereotyped reflexive behavior and that we need to shift toward understanding the goals of the nervous system to fully understand how behavior is generated. I read the book because I wanted to get a grip on the neuroeconomics and decision-making papers that are flying off the press, so the philosophical and paradigmatic issues weren't really necessary for me although they led me down some entertaining avenues of thought. If you just want an intro to neuroeconomics and the types of experiments involved, you could probably skip up to chapter 10 and read the last 100 pages or so. I think the most obvious application of this field is judicial. It seems like you could set up this problem in terms of economics and then look for neurological indicators and ?interventions?. Glimcher has addressed the law in at least one article but focused on the application of neurobiological evidence in courts. All that aside, below I just want to give you an idea of the scope of the book and the fields he draws from to make his case.

Part I: History Chapter 1: Describes beginnings of scientific method (Francis Bacon) and application to human physiology (William Harvey). He introduces Vaucanson's duck, a mechanical duck created by a Jacque de Vaucanson which will serve as a recurring symbol for the reflex-based, deterministic view of behavior. The main purpose of the chapter is to introduce Descartes and Cartesian dualism. Descartes needed the soul to explain "unpredictable and nondeterministic behaviors...that the clockwork scientific explanations available...could not hope to mechanistically explain...". Chapter 2: Lagrange and Laplace do so well in describing the physical universe with analytical mathematics that it seems certain that biological systems will also eventually succumb. In 1833, Marshall Hall presents a paper to the Royal Society in which he transected frog spinal cords and found reflexes in the bottom half and volition in the top (dualism creeping into physiology). There is more detail regarding the history of spinal reflex physiology the innerworkings of the Royal Society. Chapter 3: Charles Sherrington was a smartypants, but he is this book's villain. Sherrington conceptualized behavior in terms of the reflex-arc. A receptor organ receives a sensory stimulus, this stimulation is transmitted by way of a conductor to an effector organ. This is the simplest explanation for the reflexes that we are all familiar with, but Sherrington had to bring in inhibitory components too to explain how one muscle can tighten while one loosens in a coordinated fashion. Pavlov takes reflexes up into more complex behavior, and we start to think behavior is deterministic and if we had good maths we could explain the whole damn thing. Godel looms into view to ruin everyone's party. The Godel issue seems more like zeitgeist party-pooping than a necessarily devastating issue for the reflexological paradigm. Chapter 4: "The whole function of the nervous system can be summed up in one word, conduction." This quote will haunt Sherrington for the rest of the book. Reflex theory can't deal with spontaneous behavior (we are subjected to a thought experiment in which a cat is placed in a sensory deprivation chamber) and internally generated oscillations. We need feedback (reafference) and oscillators to explain the function of the nervous system. Also, the same goal-directed behavior can be achieved through a number of different motor programs, so the goal must be decided followed by the computation of the proper motor program, implying a hierarchy. A hierarchy is not simple conduction, so this is another challenge to the Sherrington's formulation. Chapter 5: Computational models. Classical models have an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. A speech model called NetTalk is discussed. The point is to show how much modern neurobiological models and experiments are informed by the reflex paradigm. A big chunk is devoted to explaining some interesting experiments performed by the Newsome lab demonstrating that neurons in area MT (a part of the neocortex containing neurons sensitive to moving visual stimuli) fired in direct correspondence to a monkey's reported perception of the direction of stimulus motion, and that perception could be influenced by stimulation of these neurons. Newsome employed a Michael Shadlen to model the data computationally, and they came up with a nice deterministic model to explain motion perception. Glimcher says this is all well and good, but we are limiting ourselves to unnatural experimental paradigms because of the Sherringtonian influence. Chapter 6: David Marr is one of the heroes of the book. Marr was a theorist and computer scientist who wrote a book called Vision in the late 70s as he was dying of leukemia. Marr said you can't understand flight by studying feathers. You have to understand aerodynamics. By analogy, we can't understand the nervous system by studying neurons and mechanisms, we have to use theory and understand the goals of the brain. Marr did this for visual perception, but Glimcher notes that two immediate objections arise. One is that the definition of the scope of a nervous system goal seems arbitrary, and two is that it is not clear that evolution is concerned with computational goals or that the brain does things in an efficient goal-directed way. Chapter 7: How to dissect up the nervous system to get some goals to understand. Fodor and colleagues argue that cognition is divided up into independent modules. Michael Gazzaniga, working with split-brain patients (much communication between left and right hemisphere is removed to isolate epileptic foci), shows that the different halves of the brain were specialized and can work independently. So cognition can be divided up into goals, and it doesn't have to be completely arbitrary. Gould and Lewontin show up to introduce phyletic and architectural constraints that could raise problems for Marr. Evolution may not be able to get you to the optimal computational solution. But Glimcher points out that there are cases where we are darn close to optimal. Rhodopsin is the molecule in your eye that converts light into a biochemical signal so it can influence neural firing. Rhodopsin can detect a single photon. That's as good as you could hope for. There is also a section on convergent evolution in African cichlids suggesting that an evolutionary goal may be important than how you get there. Part II: Theory and experiments Chapter 8: What's the overall goal? Maximizing inclusive fitness. "I want to suggest that we can characterize the function of the nervous system as decision making." Decision making should produce behavior that increases inclusive fitness. It is easy to make optimal decisions if you are omniscient, but organisms living in the world have to make decisions in the face of uncertainty. We need probability theory to deal with uncertainty, and we ought to define the goals of the nervous system in terms of probability theory. A history of probability theory featuring Blaise Pascal follows. Probability of an event X value of that event = Expected Value. Value doesn't predict how people will behave though. One man's trash is another's treasure and all that. Bernoulli came up with Expected Utility to describe the case in which, for instance, the same absolute amount of food (Value) is more motivating when you're hungry than when you're satiated. We get a fairly detailed description of Bayesian likelihood estimation. Bayesian theory is the optimal tool for decision-making in uncertain conditions. Economics uses these tools to predict behavior. We should use economics to define the goals of the nervous system and call it Neuroeconomics. Chapter 9: John Krebs' behavioral ecology defines optimal goals using economics and explains natural animal behavior in terms of decision-making. The "prey model" is developed in this context and uses probability theory and economic models to define the most efficient predator behavior. When should a predator bother to collect food and when should it pass? The prey model is empirically tested, and a bird called the titmouse seems shows behavior very close to that predicted by a probabilistic economic model. This shows the utility of defining behavioral goals using economic models. Chapter 10: This is the longest chapter and the meat of the book. We get an introduction to the neuroanatomy of both visual processing and motor control of the eye. Primates can be trained to move their eyes based on visual stimuli. We know how the info gets in and where it goes out, but where is the sensory input connected to motor output? Research has focused on an area that seems anatomically well-positioned for the job called the lateral intraparietal area (area LIP). A major leap occurs when Herbert Jasper and Edward Evarts develop a system for recording from single neurons in awake behaving primates. A controversy ensues in which one camp insists that parietal neurons encode high-level motor commands and another camp says they are rather involved in high-level visual processing (i.e. attention). There are a lot of experiments described with regard to this controversy. I think Glimcher is trying to illustrate how bogged down we can get when trying to interpret neuro-data using the receptor-conductor-effector model. Glimcher and Michael Platt stepped into the fray in 1997, but their major move came in 1999 when they tested the idea that the LIP was encoding economic parameters necessary for making decisions about which way to move the eyes. Neurons in the LIP have a preferred position in the visual field that they would like to fire for. Glimcher and Platt varied the probability that this location would be the target location (the place to which the monkey must move its eyes to receive a reward) across trial blocks. The firing rate of neurons in the LIP corresponded directly with the prior probability of reward at their preferred location. When, conversely, the probability of reward was held constant and the amount of reward was varied, neurons in the LIP also showed a direct relationship between activity and reward value. Probability of reward X value of a reward = Expected Value (and perhaps Expected Utility, see here for more). In the prior experiments, the monkey was eventually told by a visual cue which way to look for reward, but Glimcher wanted to ask whether monkeys make probabilistic decisions in the face of a probabilistic problem. He drew on an observation by Richard Herrnstein that pigeons could match their behavior to an experimentally controlled probability landscape, so-called Matching Behavior, to produce a paradigm in which monkeys could demonstrate their matching proficiency (even though this wasn't the optimal strategy). Monkeys did model the probability and value setup with their actions and neurons in the LIP tracked the estimated value of a given eye movement. Glimcher isn't satisfied though because the monkeys didn't perform the economically-defined optimal deterministic strategy but instead behaved probabilistically. The next chapter attempts to explain why sometimes probabilistic behavior actually is the optimal course predicted by game theory. Chapter 11: Intro to Game Theory. This is also my first real encounter with game theory, so expect me to be getting it wrong for a while. Starts with Von Neumann and Morgenstern. The optimal solution when faced with an intelligent adversary is sometimes to become as unpredictable as possible. When your best move is to vary which type of move you make you have arrived at a mixed strategy solution. You act unpredictably. VN and M only did the math to predict mixed strategy solutions in competitions in which one entity's gains are mirrored by the adversary's losses (zero-sum). John Nash was able to expand the math to include non-zero-sum games. The treatment of Nash's contribution is fairly detailed. Glimcher says that Nash allowed us to consider that nondeterministic (uncertain, probabilistic) behavior is often optimal. I'm still not clear on why this is Nash's insight instead of VN and M's, but I will take Glimcher's word for now. John Maynard Smith brings game theory into biology and evolutionary theory, and finds probabilistic behavior is evolutionarily stable. Finishes with a description of experiments by D.G.C. Harper showing that ducks behave according to the laws of economic theory. Glimcher makes kind of a big deal out of the idea that animal behavior can be 'fundamentally unpredictable' and 'irreducibly probabilistic'. I'm thinking that his usage of the term irreducible is a little uncommon. In the next chapter he attempts to discover neural correlates of this unpredictable property. This seems like a step toward reduction of the problem to me, such that if we really knew the brain, the behavior would no longer be uncertain. Chapter 12: The work or shirk game is introduced pitting a worker against a boss checking up on him. People act according to the principles discussed above and act really randomly. Glimcher and Mike Dorris took the game to a computer versus a monkey. Monkeys act right too. Neurons in the LIP fire at a consistent rate when probability and value of rewards are varied but relative expected utility is maintained. If you look at a finer grain, you can see that neurons are adjusting their firing rates with updates after each trial and that these updates work in the manner predicted by a Nash equilibrium solution. Chapter 13: This is a wrap-up chapter. Glimcher proposes a bunch of other experiments he's done or would like to do. He has a couple concerning visual attention and motion. Some on the neurobiology of encoding prior probabilities. He mentions the basal ganglia as a potential spot for this type of learning, but doesn't really review what the basal ganglia is/are all about. There is also some on the encoding of value and how dopamine might be involved. Chapter 14: This is the second wrap-up chapter focused on philosophy. Descartes was wrong. We don't need dualism. We don't need reflexes at all. We need a continuum of behavior from probabilistic to deterministic. He seems to have a pretty nice take on free will. "Free will may simply be the name we give to the probabilistic behaviors that are mixed strategy solutions. Our subjective experience when a mixed strategy solution requires the activation of a lawful neuronal randomizer." Return to Vaucanson's duck. Animals act indeterminately aaaand they don't have to have souls to do it. Hope this gets some people interested in reading the book and maybe getting further into the area. I am going to be trying to discuss some of this stuff as it comes out. In general, I get more excited about brain mechanisms than ecology or theory, but these perspectives seem to have been really important in developing Glimcher's views. I could've stood for a little more neuroscience background. We got a fairly good treatment of the LIP, but I'm really not familiar with single-neuron recording, and I'm sure there are caveats and pitfalls to this research technique (one being that it is purely correlational). One obvious next move is to either attempt to manipulate expected utility behavior by stimulating this area or to affect the same by ablating the area.

Friday, August 25, 2006

The Golden Rule & Christian altruism, God & conservatism part n... and God & morality are follow ups on the Heather Mac Donald vs. the Right who are religious saga. Heather has received a lot of flack from her political fellow travellers, and though I don't necessarily agree with every element of Heather's argument, I do think the Right has moved too far in soaking its arguments with the imprimatur of divine sanction. Ramesh Ponnuru made big noises about how his argument in Party of Death was not religious, but most outside of the Right ignored him because they simply can not conceive of any conservative argument as not having a religious tinge (I think this preconception is false, but, I think it is supported by the close connection between evangelical religious groups and modern conservatism). The Right does not need to turn to Randian godlessness, rather, it should perhaps temper some of its populist evangelicaism so to as spread the tent a bit bigger. (Also, check out Right Reason for responses to some of my posts. Does anyone know how many blogs Steve Burton contributes to? Besides God that is)

Also, two posts on hybridization in the human context. Pictures too.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Interesting paper I found Sex, status, and reproductive success in the contemporary United States (PDF). Since you can read the whole paper, I won't summarize it for you, but below the fold is a graph that some might find of interest.

You've probably heard about the new technique to facilitate the use of embryonic stem cells without destroying them? Devil Boy Jake has a science oriented review, and Poreless Anthis has a more public policy focused post. I have no particular insights on this topic, as I noted in my own post, though in the comments godless offered a comment which reflected some of my own cautious perceptions, to which Darwin Catholic responded. Over at The Corner not a word out of Ponnuru, and Lopez is rather subdued, so perhaps much ado about nothing....