|

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Why do we delay gratification even when there is no downside?

posted by

agnostic @ 12/29/2009 09:10:00 PM

Earlier this year, John Tierney reviewed several studies on how delaying gratification makes us feel better in the short term by preventing guilt but makes us feel more miserable in the long term by causing regret over missed opportunities. I added my two cents here, just to note that this sounds like part of the Greg Clark story about recent genetic change in the commercial races that adapted them to the emerging mercantile societies they found themselves in. What I had in mind was the delaying of vice -- investing a dollar today rather than splurging, moderating the amount of drink or sweets you enjoy, and so on.

But now Tierney has another review of related studies which show that we delay gratification even for what should be guilt-free pleasures like redeeming a gift card, using frequent flier miles, and visiting the landmarks in your local area. And don't we all have enjoyable books and DVDs we've been putting off? After indulging in these cases, there is no potential bankruptcy, no hangover, and no tooth decay -- so why do we indiscriminately lump them in with genuine vices and put off indulging in them? Obviously this tendency too is a feature of agrarian or industrial groups -- hunter-gatherers would never leave gift cards lying around in their drawers. It must be because of how recent the change toward delaying gratification has been. Given enough time, we might evolve a specialized module for delaying gratification in vices and another module for doing so in guilt-free pleasures, which would be better than where we are now. But when our genetic response to a change is abrupt, typically we have broad-brush solutions that take care of the intended target but also leave plenty of collateral damage. Over time our solutions get smarter, but it takes awhile. Just look at how crude the responses to malaria are. We see this domain-general taste for (or aversion of) risk in other areas. People who lead more risky lifestyles buy much less insurance than people who lead cautious lifestyles. Those who ride motorcycles without helmets would be richer and more likely to pass on their genes if they bought a lot of insurance, while those who play it safe would be richer by not buying all that superfluous insurance. Instead, daredevils are daredevils all the way -- including a contempt for insurance. This casts doubt on how easy it is to change our behavior so that we no longer postpone our indulgence in guilt-free pleasures. Because we have a domain-general delay of gratification, it will still just feel wrong. You can also argue the logic of buying lots of insurance to the motorcyclist who rides without a helmet, but that won't change his mind because his tastes for risk is across-the-board. Labels: Behavioral Economics, Psychology

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Tyler Cowen points me to this article from last spring about the profligacy of professional athletes. Here are numbers which seem constructed for the sake of plausibility more than anything else:

* By the time they have been retired for two years, 78% of former NFL players have gone bankrupt or are under financial stress because of joblessness or divorce. It shouldn't be that hard to track down a large number of former players and try and make the sample representative, and assess what their financial situation is. This looks like a "natural experiment" waiting to be mined for data (perhaps someone already has, if so, pointers in the comments welcome). Here's the part which shows time preference inclinations most starkly: Given all the pressures on a pro athlete's marriage, one safety valve might be the prenuptial agreement-something "very strongly" recommended by agent David Falk, who surged to prominence representing Michael Jordan (who did not have one). "The percentage of prenups amongst athletes is appreciably lower compared with nonathletes at the same economic level," says celebrity divorce lawyer Raoul Felder, who has represented the ex-wives of Patrick Ewing, Jason Kidd and Mike Tyson. Mutumbo as an exceptional case is informative, he was not recruited as a student athlete initially, and managed to complete a degree in linguistics and diplomacy at Georgetown (David Robinson, who scored a 1320 on the pre-recentered SAT and received a degree in math from the Naval Academy, is probably an even better example). Labels: Behavioral Economics

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Expectations influence sensory experience in a wine tasting:

Information about a product may shape consumers' taste experience. In a wine tasting experiment, participants received (positive or negative) information about the wine prior to or after the tasting. When the information was given prior to the tasting, negative information about the wine resulted in lower ratings compared to the group that received positive information. No such effect was observed when participants received the information after the tasting but before they evaluated the wine. Results suggest that the information about the wine affected the experience itself and not only participants’ overall assessment of the wine after the tasting. Also, see ScienceDaily for a summary. Felix Salmon has another post, Tasting wine blind. Labels: Behavioral Economics, Wine

Monday, August 24, 2009

Gender differences in financial risk aversion and career choices are affected by testosterone:

Women are generally more risk averse than men. We investigated whether between- and within-gender variation in financial risk aversion was accounted for by variation in salivary concentrations of testosterone and in markers of prenatal testosterone exposure in a sample of >500 MBA students. Higher levels of circulating testosterone were associated with lower risk aversion among women, but not among men. At comparably low concentrations of salivary testosterone, however, the gender difference in risk aversion disappeared, suggesting that testosterone has nonlinear effects on risk aversion regardless of gender. A similar relationship between risk aversion and testosterone was also found using markers of prenatal testosterone exposure. Finally, both testosterone levels and risk aversion predicted career choices after graduation: Individuals high in testosterone and low in risk aversion were more likely to choose risky careers in finance. These results suggest that testosterone has both organizational and activational effects on risk-sensitive financial decisions and long-term career choices. Labels: Behavioral Economics

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

The greater fool theory 1: A mostly verbal mathematical model

posted by

agnostic @ 8/19/2009 09:22:00 PM

Here is a brief description of the idea that price bubbles are caused by people buying something, not necessarily because they think it's worth anything, but because they think they can find an even greater fool to buy it at a higher price. This continues until no more such fools can be found, and this bust drives prices back down to what they were before the boom began.

I didn't see any references to mathematical models of the theory at Wikipedia or through Googling around a bit, so I made one up today at Starbucks since I didn't have anything to read to pass the time. Because I'm not an economist, I don't know how original it is, or how it compares with alternative models of the greater fool theory (if they exist). So, this is intended just as an exercise in modeling, explaining the model, and hopefully shedding some light on how the world works. I've kept most of the exposition straightforward and largely verbal, so that you don't need to know much math at all to understand what the model says and what its implications are. In part 1, I lay out the logic of the model and explain enough of it to show that it is capable of producing a single round of boom-and-bust for price hype. Part 2 will provide more mathematical detail about how the dynamics unfold, a phase plane analysis, and graphs of how the variables of interest would change over time, to better wrap your brain around what the model predicts. This is a dynamic model, or one that tracks how things change over time -- after all, we want to see how price, the number of fools, etc., evolves. It is made of several differential equations, and all these equations say is what causes something of interest to go up or go down over time. (You may recall that the sign of a derivative tells you whether a function is increasing or decreasing, and the magnitude says by how much.) I'll only explain what is absolutely necessary for the reader to see what's going on, with the less necessary math being confined to footnotes. First, we set up the basic picture before we write down equations. My version of the greater fool theory goes like this. There is a population of people, and during a price bubble they can fall into three mutually exclusive groups: suckers (S), who are susceptible to joining in on the bubble; investors (I), who currently own the speculative stuff (such as a home bought for speculation); and those who are retired from the bubble (R), who used to be investors but have gotten rid of their investment. And of course there is the price of the thing -- I model only the extra price that it enjoys due to hype (P), above its fundamental value, since this is the only component of price that changes radically during the bubble. I set the population to be fixed in size during the bubble, since growth or decline is negligible over the handful of years that the bubble lasts. I also set the amount of speculative stuff to be fixed, which is less general -- supply should shoot up to meet the rising demand during a bubble. So, this model is restricted to cases where you can't produce lots more of the stuff, relative to how much already exists, on the time-scale of the bubble's boom stage (say, 5 years or less). Or perhaps no more of it will be produced at all, such as video game consoles from decades ago that the original manufacturers will never bring back into production, but which nostalgic fans have taken to buying and selling speculatively (like NEC's TurboDuo). Last, the amount of stuff that each investor has is the same across all investors and stays constant -- say, if each investor always owned just one speculative home. At the start of the bubble, there is a certain number of early investors. In order to sell their stuff, they need to meet a sucker to sell it to. When they meet -- and I assume the two groups are moving around independently of each other -- there is a probability that the sale will be made. If they make a deal, the sucker is now an investor, and the former investor is now retired. In this model, retireds do not again become suckers -- they consider themselves lucky to have found a greater fool and stay out of the bubble for good afterward. That's the extent of how people change between groups. As for price hype, again I'm not an economist, so the exact formula may differ from what's standard. I take it to respond positively to demand -- namely, the number of suckers -- and that there is a multiplier that serves as a reality check. This reality check should be weak at the start when most non-investors are suckers, and should be strong near the end when most non-investors are retired. In other words, the price hype at the beginning is a near total distortion -- nearly 0% accurate -- whereas the price hype near the end is nearly 100% accurate. This will make more sense once we write down formulas. Now we get to the differential equations for how these things change. We write down one equation for each variable whose values we're tracking over time. I use apostrophes to denote the derivative with respect to time (i.e., rate of change): S' = -aSI Since suckers can only lose members (by turning into investors), there is only one term, and it shows how suckers decline (negative sign). Remember, retireds do not go back into the pool of potential buyers. And investors either make a sale and go into the retired group, or they sit on their stuff in hope of selling, so they never contribute to the growth of suckers. Thus, there is no growth term. The parameter a shows the probability that, when a sucker and an investor meet, the investor will transfer his stuff to the sucker. ("Parameter" is another word for "constant," in contrast to a variable that changes.) The reason we use the product of S and I is that this is essentially the rate at which the two groups encounter each other when they move around independently of each other. [1] I' = aSI - aSI = 0 Investors both grow and decline, so one term is positive and the other negative. They grow by having a sucker join their ranks, which as we saw above happens at rate aSI. However, each time that happens, the investor loses his stuff and becomes retired. That happens at the same rate, and the negative sign just shows that this causes I to decline. When we simplify, we get I' = 0 -- that is, the number of investors does not change over time. That makes sense because each bundle of stuff always has an owner, regardless of how it may change hands, somewhat like the game of hot potato. When something doesn't change, it is constant, so whenever we see I from now on, we'll know that this is just another parameter, not a variable that changes. In particular, it refers to the initial number of early investors who get the bubble going. R' = aSI Retireds never join the suckers again. And recall the mindset of a retired person -- they knew the stuff was junk and are glad to have gotten through the selling process, so they cannot be sold the stuff again to become investors once more. Thus, there is no way for them to lose numbers. They grow by former investors making a sale and becoming retired, which once again happens at rate aSI. Here's the neat thing: notice that S' + R' = -aSI + aSI = 0. The sum of the two derivatives equals zero, and since taking a derivative shows the distributive property, this also means that (S + R)' = 0. That is, the sum of suckers and retireds does not change over time. This makes sense since, if the number of investors stays constant, the leftovers -- suckers and retireds -- is constant, regardless of how each separate group grows or shrinks. We can take this further to note that S' + I' + R' = 0, which means (S + I + R)' = 0. That is, the combined size of all three groups does not change over time -- which is just what we claimed by keeping total population size constant. (Otherwise, each group would have birth and death terms, aside from the terms that show how their members switch between groups.) We'll call this constant total population size N. So, S + I + R = N. Now, I is just a constant, so we'll move it to the other side: S + R = N - I. We have two variables, S and R, but we just wrote an equation connecting them, so we can re-write one in terms of the other. I'll choose R, but it doesn't matter. So, R = N - I - S, and anywhere we see R, we can replace it with N - I - S. In other words, we've removed R from our focus -- we can always get it from knowing what the variable S is, as well as the two parameters N and I. That means the equation for R' only gives us redundant information, and we can ignore it. We can also ignore the I' equation, since it just tells us that I is constant, and we're only interested in things that change. So we're left with just the S' equation. Now we move on to the price hype formula and how it changes over time. First, the formula for price as a function of demand and the reality check, since hype is never totally irrational and at least tries to take stock of reality: P = bS(R / Rmax) = bS(R / (N - I)) Demand is driven by the number of suckers -- the ones who eventually want to get in on the bubble -- and the parameter b says how strongly demand responds to the number of suckers. The multiplier (R / Rmax) provides a reality check. If you landed from Mars and only knew the number of suckers, you would also want to know how many retireds there were -- if there were few retireds, that would tell you the bubble had only just begun, so that hype is likely to be high and to go even higher short-term. Thus, this filter should not let much of the demand information through. Indeed, when R is very low compared to Rmax, the multiplier is near 0. However, if you saw that there were many retireds, that would say the bubble was near its bust moment, and that the information from demand is very accurate by this point. Indeed, when R is near Rmax, the multiplier is near 1 and the filter lets just about all of the demand information through. What is Rmax? It is the value when no one is a sucker and everyone is retired, aside from the constant number of investors. Looking above at the equation S + R = N - I, we see that when there are no suckers, R = N - I. Now we need to find the differential equation for how P changes over time. Using the product rule for derivatives [2], we get: P' = (abI / (N - I)) * S(2S + I - N) Since a, b, I, and N - I are always positive, and since S is positive except for the very end of the bubble when it is 0, in the meantime, whether price hype shoots up or crashes down depends on whether the term 2S + I - N is positive or negative. It is positive and price hype grows when S exceeds (N - I) / 2, which is half the size of non-investors. It is negative and price hype declines when S is below (N - I) / 2. It is 0 and price hype momentarily stalls out when S is exactly (N - I) / 2. Because the bubble starts with all non-investors being suckers, S is initially N - I, which is greater than (N - I) / 2. So at first the price hype shoots up. However, remember that S only declines -- as more and more of the suckers are drawn into the bubble (some of whom may also make sales and become retireds), S will inevitably fall below (N - I) / 2 and price hype will start to contract. When S inevitably reaches 0 -- when all non-investors are out of the bubble for good -- then P = 0 (recall that P = bS(R / Rmax)). Moreover, at that time P' = 0 too. Thus, at the end, price hype has completely evaporated and it will stay that way. This is a single round of boom-and-bust for price hype. In this post, I've shown how some pretty simple "greater fool" dynamics can lead to a boom-and-bust pattern for price hype. You can quibble with all of the assumptions I've made, but the model shows that the greater fools theory is a viable explanation for price bubbles. I've relaxed some of the assumptions to see if it makes a difference, like making the decline of S be a saturating rather than linear function of S, and so far they don't seem to affect things qualitatively. A more realistic model would have P appear in the equation for S' -- that is, to have price hype affect the probability of making a sale. Or rather, the trend of prices (P' ) should affect sale probability -- if suckers see that price hype is increasing, they should want to get in on the bubble, and to stay put if price hype is dropping. Also, allowing retireds to re-enter the pool of suckers would be more general and would almost certainly lead to sustained cycles of boom-and-bust, rather than a single round. But that's for another slow afternoon. In part 2, I'll go into more mathematical detail about how we see what states this system is at rest in, and whether they are stable to disruptions or not. I'll look more at the formula for the maximum level of price hype, and interpret that in real-world terms in order to see what things will give us larger-amplitude bubbles. I'll provide a picture of the phase plane, which shows what the equilibrium points are, and how the variables will change in value on their way from their starting values to the final ones. I'll also have a couple of graphs showing how the number of suckers and retireds, and the amount of price hype, change over time. [1] Draw one person at random, and the chance that they're a sucker reflects S. Draw another one at random, and the chance that they're an investor reflects I, since the draws are independent. The chance of doing both is just the product of the two separate probabilities. [2] P' = (bS(R / Rmax))' = (b / (Rmax)) (S' * R + S * R') A little algebra, which you can confirm by hand or using Maple, gives the equation in the main body for P'. Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics, mathematics, Modeling

Sunday, July 12, 2009

Robert Frank is promoting his idea that Charles Darwin will become more important than Adam Smith as an intellectual forebear of future economics in The New York Times. That is fine as it goes but I suspect that the bigger issue in the sciences of humanity is that there will be problems with relying on only one disciplinary framework and one general model. For example Frank points out that evolutionary fitness is generally conceived of in a relative sense (population mean fitness being the baseline), but the same dynamic crops up in neuroscience due to biophysical computational efficiencies from relative heuristics as opposed to a laundry list of absolute fixed preferences. R. A. Fisher famously wished to lay the seedbed for a thermodynamics of evolution in The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Whether one can envisage this in evolutionary genetics, it seems even less likely in the human sciences, at least to the extent of making a generalization which is not trivial. The rut which orthodox evolutionary psychology has found itself in is probably due to this assumption that our species is at some biobehavioral equilibrium due to an exceedingly unrealistic model of evolutionary dynamics.

Labels: Behavior Genetics, Behavioral Economics, Economics

Thursday, July 02, 2009

In the new issue of The New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell reviews some book about using the appeal of FREE to grow your business. This is supposed to apply most strongly to information, so that as more and more of a firm's product / service consists of information, the more it can use the appeal of FREE to earn money.

What both Gladwell and the reviewed book's author, Chris Anderson, don't seem to realize is that the appeal of FREE creates pathological behavior. Gladwell even cites a revealing behavioral economics experiment by Dan Ariely: Ariely offered a group of subjects a choice between two kinds of chocolate -- Hershey's Kisses, for one cent, and Lindt truffles, for fifteen cents. Three-quarters of the subjects chose the truffles. Then he redid the experiment, reducing the price of both chocolates by one cent. The Kisses were now free. What happened? The order of preference was reversed. Sixty-nine per cent of the subjects chose the Kisses. The price difference between the two chocolates was exactly the same, but that magic word "free" has the power to create a consumer stampede. In other words, FREE caused people to choose an inferior product more than they would have if the prices were both positive. Thus, in a world where there is more FREE stuff, the quality of stuff will decline. It's hard to believe that this needs to be pointed out. And again, this is not the same as prices declining because technology has become more efficient -- prices are still above 0 in that case. FREE lives in a world of its own. If you're only trying to get people to buy your target product by packaging it with a FREE trinket, then that's fine. You're still selling something, but just drawing the customer in with FREE stuff. This jibes with another behavioral economics finding -- that when two items A and B are similar to each other but very different from item C, all lying on the same utility curve, people ignore C because it's hard to compare it to the altneratives. They end up hyper-comparing A and B since their features are so similar, and whichever one is marginally better wins. So if you have three more or less equally useful products, A B and C, where B is essentially what A is, just with something FREE thrown in, people find it a no-brainer to choose B. An exception to the rule of "FREE leads to lower quality" might be the products that result from dick-swinging competitions, where the producer will churn out lots of FREE stuff just to show how great they are at what they do. They're concerned more with reputation than getting by. Academic work could be an example -- lots of nerds post and critique scientific work at arXiv, PLoS, as well as the more quantitatively oriented blogs. But in general, you can imagine the quality level you'd enjoy from a free car or an all-volunteer police force. Even sticking with just information, per Chris Anderson, look at what movies you can download without cost on a peer-to-peer site or whatever -- they mostly all suck, being limited to the library of DVDs that geeks own. Sign up for NetFlix or a similar service, and you have access to a superior library of movies, and it hardly costs you anything -- it's just not FREE. Ditto for music files you can download cost-free from a P2P site vs. iTunes, or even buying the actual CD used from Amazon or eBay. Admittedly I don't know much about computer security, but just by extending the analogy of a voluntary police force, I'd wager that security software that costs anything is better than FREE or open source security software. To summarize, though, Gladwell's discussion about FREE misses the most important part -- it tends to lower quality. I don't want to live in a word of lower quality of items that aren't of major consequence, and (hopefully) the people in charge of high-consequence items like the police and my workplace's computer security will never be persuaded to go for FREE crap in the first place. This aspect alone answers the question he poses in the sub-headline, "Is free the future?" However, wrapping your brain around the idea that FREE tends to lower quality is discordant with a Progressive worldview, which explains why Gladwell just doesn't get it. Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics, Media, Technology

Friday, May 22, 2009

The Science of Fear, and some data on media overhyping of crime risks

posted by

agnostic @ 5/22/2009 02:10:00 AM

Since the world started falling apart, books on how crazy we are have never been more popular. Most focus on findings from behavior economics that show how human beings deviate from homo economicus in making decisions, and The Science of Fear by Daniel Gardner is no different. Unlike the others in this newly sexy genre, though, he doesn't look at economic decisions very much, but instead on how we assess risk -- sometimes to our own harm. Consider those who, in the panic after 9/11, switched from riding airplanes to the more dangerous mode of cars and died in car crashes.

I won't review the book at length since it's an easy read and well written -- worth adding to your "crazy fucking humans" summer reading list. For a taste, though, here's the author speaking on The Leonard Lopate Show. Gardner spends some time discussing how outta-whack the media coverage of a problem is with the underlying risk, as when silicone breast implants for awhile appeared to be the next cigarette or trans fat. Over at my personal blog, I put up two entries that have graphs showing, from 1981 to 2007, the per capita rates of homicide and forcible rape (risk), the fraction of all NYT articles that mentioned "murder" or "rape" (coverage), and the coverage-to-risk ratio (overhyping). Here's the homicide post and the rape post. In both cases, sometime in the early-mid 1990s, in the wake of a generalized hysteria -- identity politics, L.A. riots, Third Wave feminism, blaming AIDS on Regan, etc. -- the overhyping starts to take off and has remained high up through recent years. We've never been safer, yet we've only grown more paranoid. Labels: Behavioral Economics, crime, culture, Media, News

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

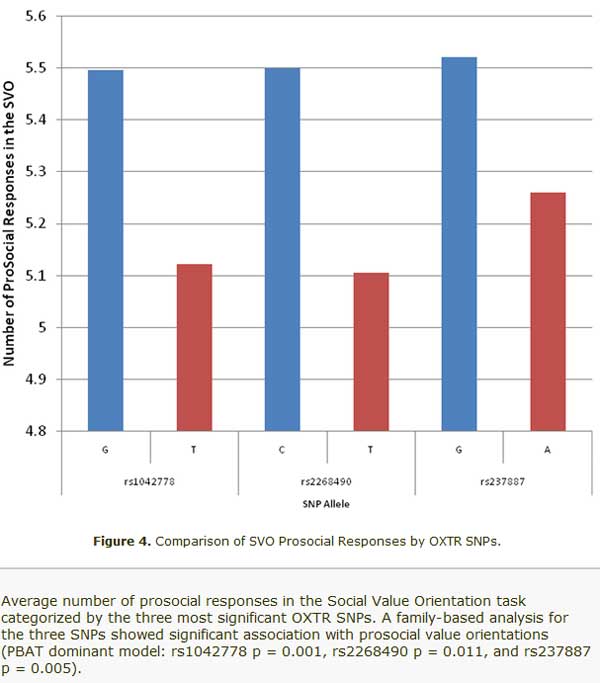

The Oxytocin Receptor (OXTR) Contributes to Prosocial Fund Allocations in the Dictator Game and the Social Value Orientations Task:

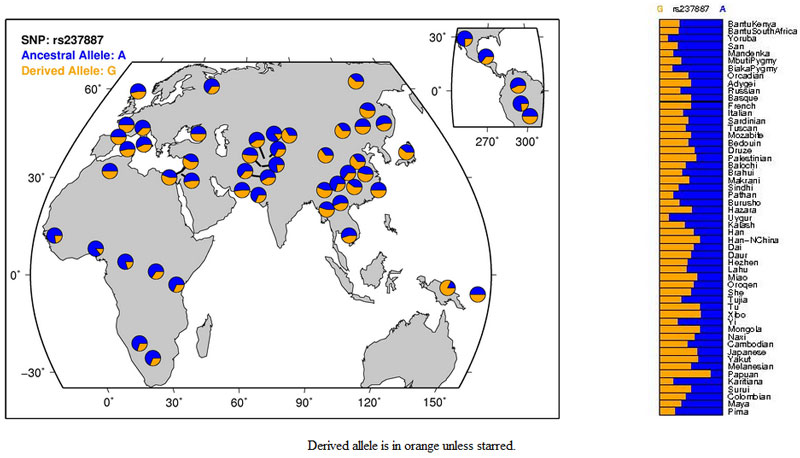

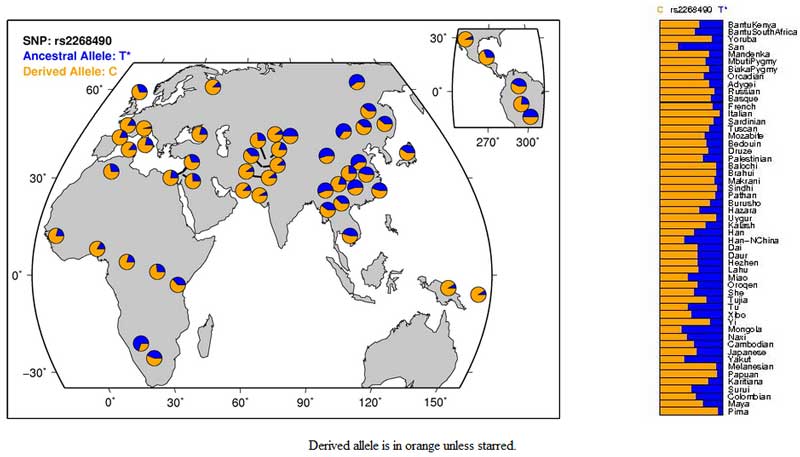

The demonstration that genetic polymorphisms for the OXTR are associated with human prosocial decision making converges with a large body of animal research showing that oxytocin is an important social hormone across vertebrates including Homo sapiens. Individual differences in prosocial behavior have been shown by twin studies to have a substantial genetic basis and the current investigation demonstrates that common variants in the oxytocin receptor gene, an important element of mammalian social circuitry, underlie such individual differences. Here's a figure from the paper:  And the SNPs from the HGDP (G = C & A = T for the first SNP, or at least the paper and PubMed agree on this):    Related: It's hard out here for a vole. Heritability of the Ultimatum Game. Altruism and Risk-Taking: Kinda Heritable. Can someone put the psychic unity of makind out of its misery? DRD4, politics & friendship. Labels: Behavior Genetics, Behavioral Economics, Genetics

Sunday, May 10, 2009

A Genetically Mediated Bias in Decision Making Driven by Failure of Amygdala Control:

Genetic variation at the serotonin transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) is associated with altered amygdala reactivity and lack of prefrontal regulatory control. Similar regions mediate decision-making biases driven by contextual cues and ambiguity, for example the "framing effect." We hypothesized that individuals hemozygous for the short (s) allele at the 5-HTTLPR would be more susceptible to framing. Participants, selected as homozygous for either the long (la) or s allele, performed a decision-making task where they made choices between receiving an amount of money for certain and taking a gamble. A strong bias was evident toward choosing the certain option when the option was phrased in terms of gains and toward gambling when the decision was phrased in terms of losses (the frame effect). Critically, this bias was significantly greater in the ss group compared with the lala group. In simultaneously acquired functional magnetic resonance imaging data, the ss group showed greater amygdala during choices made in accord, compared with those made counter to the frame, an effect not seen in the lala group. These differences were also mirrored by differences in anterior cingulate-amygdala coupling between the genotype groups during decision making. Specifically, lala participants showed increased coupling during choices made counter to, relative to those made in accord with, the frame, with no such effect evident in ss participants. These data suggest that genetically mediated differences in prefrontal–amygdala interactions underpin interindividual differences in economic decision making. Check out the Wikipedia entry on 5-HTTLPR; lots of behavioral phenotypes associated with this variant. ScienceDaily: The researchers also measured the degree of interaction, or connectivity, between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, the brain region most implicated in human intelligence, personality and decision making. When resisting the frame effect, the participants with two copies of the long variant had stronger connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, while those with a pair of short variants did not. So this genetic variation only explains 10% of the variation within the population when it comes to frame effect in behavioral economics. Fair enough. But, I do wonder if in the current political environment fewer would oppose genetically black-balling individuals with the short variants of 5-HTTLPR from becoming traders! (I'm not proposing this seriously myself, but I think there might be some amygdala-driven acceptance of this sort of genetic profiling right now even if the returns are small) Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics, Neuroscience

Friday, April 24, 2009

Cognitive skills affect economic preferences, strategic behavior, and job attachment:

Economic analysis has so far said little about how an individual's cognitive skills (CS) are related to the individual's economic preferences in different choice domains, such as risk taking or saving, and how preferences in different domains are related to each other. Using a sample of 1,000 trainee truckers we report three findings. First, there is a strong and significant relationship between an individual's CS and preferences. Individuals with better CS are more patient, in both short- and long-run. Better CS are also associated with a greater willingness to take calculated risks. Second, CS predict social awareness and choices in a sequential Prisoner's Dilemma game. Subjects with better CS more accurately forecast others' behavior and differentiate their behavior as a second mover more strongly depending on the first-mover's choice. Third, CS, and in particular, the ability to plan, strongly predict perseverance on the job in a setting with a substantial financial penalty for early exit. Consistent with CS being a common factor in all of these preferences and behaviors, we find a strong pattern of correlation among them. These results, taken together with the theoretical explanation we offer for the relationships we find, suggest that higher CS systematically affect preferences and choices in ways that favor economic success. From the discussion: The novel relationships we find have potentially deep implications. For example, Gregory Clark recently suggested that the initial location of the industrial revolution in England may have been due to a "survival of the richest" selection process, that operated there from as early as 1250 C.E...This selection may have been cultural, genetic, or both. He suggests that selection favored "capitalist" traits that include several of the ones (e.g. risk taking and saving propensity) we analyze herein. Were these traits independent, it is hard to imagine how a selection process could induce such a bundled concentration in the time frame suggested. But if these traits are correlated due to their linkage with cognitive skills, then a "selection of the richest" explanation, operating through selection for cognitive skills, becomes more plausible.... Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Steve points out that Geoffrey Miller has a new book that's going to come out soon, Spent: Sex, Evolution, and Consumer Behavior. More directly related to the topic of sex and decision-making, The Heat of the Moment: The Effect of Sexual Arousal on Sexual Decision Making. Read the whole paper, but I have a figure from it below....

Labels: Behavioral Economics |