|

Tuesday, September 01, 2009

The Worst NYT Trend Story of the Year?:

Here's an early autumnal contender: Virginia Heffernan's entirely anecdotal story about a massive Facebook Exodus. How serious is this Facebook exodus? Heffernan explains:The exodus is not evident from the site's overall numbers. This is a serious problem. Anecdotes add spice to real data. As illustrations of something real. Too often journalism involves finding five people on the street who can agree with whatever "trend" you've made up. This reminds of how I was taught to write essays in Middle School, make up a thesis and find n facts to support the thesis. Who cares if those facts are representative of the distribution of facts in the real world! You got your thesis and you know what you are looking for. And secondarily, there is the problem of trends are so widely accepted as to become background assumptions, but which turn out to be false upon even cursory examination.

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Web 2.0 party is over -- you're going to pay for the news again, and hopefully more

posted by

agnostic @ 8/27/2009 12:52:00 AM

Recently at my personal blog I've been focusing on the idiocy of Web 2.0's central strategy for growth, namely creating online networks or communities where costly participation is given away for free. (The profitable online papers charge, YouTube and Facebook still not profitable, and a more general round-up of the second dot-com bust.) The hope was that hosting a free party with an open bar would attract a large crowd, and that this in turn would lead to ever-increasing ad revenues. That business model was doomed to failure during the first dot-com boom, and it is just as doomed during the second one (Web 2.0). In the meantime, following this strategy leads to cultural output typical of attention whores rather than the output of inventors and creators with secure patronage.

I was delighted today to discover that all of this is about to change. It's still pretty hush-hush -- no "buzz in the blogosphere" -- as I've read a fair number of articles on the topic, yet none has mentioned the coming change, even if they've mentioned the change earlier in the year. Starting sometime this fall, online newspapers will finally start to charge for access to their sites, although who they charge, how much, and in what manner (yearly, per article, etc.), is entirely up to the individual papers, and we don't know what shape that will take just yet. The business model of Journalism Online, the group that's spearheading the change, says they're aiming to get revenues from the top 10% of readers by visit frequency. In any case, the point is that the era of unlimited free access to online journalism is dead. Journalism Online seems to be a central hub that readers will go through to get to the various member organizations' publications, perhaps the way college students go through their university library's website to get access to various journals. According to co-founder Leo Hindery (as I heard on Bloomberg TV today), there are over 600 papers on board, and you can bet that includes most or all of the big ones, as they provide the best quality and yet receive no money from users (other than the FT and WSJ). All of the customer's payments will be kept track of through this one site. I don't have much more detail to give, since the Journalism Online website lays it out succinctly. Go read through the business model section and the press section (the 31-page PDF listed under "Industry Reports" is the most detailed). This is the first nail in the coffin of Web 2.0, and once the other give-it-away internet companies see how profitable it is to actually -- gasp! -- charge for your product, they will wake up from their pipe dream of growing by attracting a big crowd and pushing ads. YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, perhaps other components of Google, Wikipedia -- they can either charge and profit or get shoved out of the market by those who are growing by charging. The winners will have more to invest in improving their products and maybe even funding their industry's equivalent of basic R&D, we'll see a cultural output that won't pander quite so much to the lowest common denominator to chase ad revenue, and best of all -- the quality newspapers, social networking sites, and so on, will continue to exist and grow rather than be claimed as further casualties of the moronic dot-com boom mentality. At last the internet is sobering up from its 15-year Bender of Free. Labels: Economics, Media, Technology

Thursday, July 02, 2009

In the new issue of The New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell reviews some book about using the appeal of FREE to grow your business. This is supposed to apply most strongly to information, so that as more and more of a firm's product / service consists of information, the more it can use the appeal of FREE to earn money.

What both Gladwell and the reviewed book's author, Chris Anderson, don't seem to realize is that the appeal of FREE creates pathological behavior. Gladwell even cites a revealing behavioral economics experiment by Dan Ariely: Ariely offered a group of subjects a choice between two kinds of chocolate -- Hershey's Kisses, for one cent, and Lindt truffles, for fifteen cents. Three-quarters of the subjects chose the truffles. Then he redid the experiment, reducing the price of both chocolates by one cent. The Kisses were now free. What happened? The order of preference was reversed. Sixty-nine per cent of the subjects chose the Kisses. The price difference between the two chocolates was exactly the same, but that magic word "free" has the power to create a consumer stampede. In other words, FREE caused people to choose an inferior product more than they would have if the prices were both positive. Thus, in a world where there is more FREE stuff, the quality of stuff will decline. It's hard to believe that this needs to be pointed out. And again, this is not the same as prices declining because technology has become more efficient -- prices are still above 0 in that case. FREE lives in a world of its own. If you're only trying to get people to buy your target product by packaging it with a FREE trinket, then that's fine. You're still selling something, but just drawing the customer in with FREE stuff. This jibes with another behavioral economics finding -- that when two items A and B are similar to each other but very different from item C, all lying on the same utility curve, people ignore C because it's hard to compare it to the altneratives. They end up hyper-comparing A and B since their features are so similar, and whichever one is marginally better wins. So if you have three more or less equally useful products, A B and C, where B is essentially what A is, just with something FREE thrown in, people find it a no-brainer to choose B. An exception to the rule of "FREE leads to lower quality" might be the products that result from dick-swinging competitions, where the producer will churn out lots of FREE stuff just to show how great they are at what they do. They're concerned more with reputation than getting by. Academic work could be an example -- lots of nerds post and critique scientific work at arXiv, PLoS, as well as the more quantitatively oriented blogs. But in general, you can imagine the quality level you'd enjoy from a free car or an all-volunteer police force. Even sticking with just information, per Chris Anderson, look at what movies you can download without cost on a peer-to-peer site or whatever -- they mostly all suck, being limited to the library of DVDs that geeks own. Sign up for NetFlix or a similar service, and you have access to a superior library of movies, and it hardly costs you anything -- it's just not FREE. Ditto for music files you can download cost-free from a P2P site vs. iTunes, or even buying the actual CD used from Amazon or eBay. Admittedly I don't know much about computer security, but just by extending the analogy of a voluntary police force, I'd wager that security software that costs anything is better than FREE or open source security software. To summarize, though, Gladwell's discussion about FREE misses the most important part -- it tends to lower quality. I don't want to live in a word of lower quality of items that aren't of major consequence, and (hopefully) the people in charge of high-consequence items like the police and my workplace's computer security will never be persuaded to go for FREE crap in the first place. This aspect alone answers the question he poses in the sub-headline, "Is free the future?" However, wrapping your brain around the idea that FREE tends to lower quality is discordant with a Progressive worldview, which explains why Gladwell just doesn't get it. Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics, Media, Technology

Tuesday, June 02, 2009

Click the tab below the body of this post to read previous entries in the series about how previous generations were more depraved. One way to look at how civilized we are is to see how we behave in situations where our conduct can mean the difference between life and death for those around us -- for example, when we drive our car. Traffic deaths, of course, reflect properties of the car as much as the people involved, but teasing the two apart turns out to be pretty simple in this case.

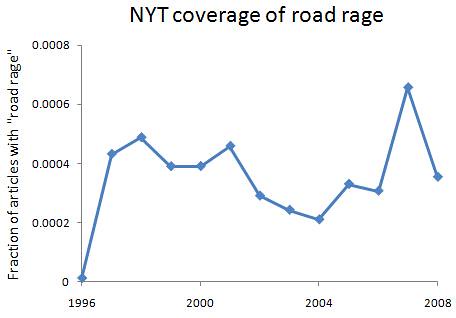

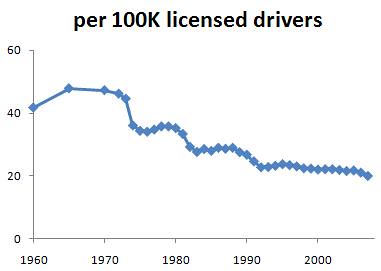

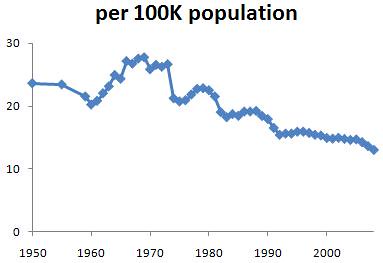

In my brief review of Daniel Gardner's book The Science of Fear, I gave a few examples of how media coverage of some threat was outta-whack with the underlying risk, namely homicide and rape. Gardner spends a few pages talking about the epidemic of "road rage" that was allegedly sweeping across the country not too long ago, so why don't we have a look at what the data really say about when road rage may have been greater than usual. First, here's a quick view of media coverage of "road rage," which begins in 1996:  What about actual traffic deaths, though? The data come from the National Safety Council, as recorded across several versions of the Statistical Abstract of the United States -- which, btw, is much cooler than the General Social Survey or the World Values Survey if you want to waste some time crunching numbers. I tracked the data back as far as they exist in the Stat Ab, and they include four ways of measuring traffic death rates. Here are the graphs:     The first is the most instructive -- it measures the number of deaths compared to the number of vehicles on the road and how long they're on the road. The other three measure deaths compared to some population size -- of vehicles, of drivers, or of the whole country -- but even if population size is constant, we expect more deaths if people drive a lot more. The distinction isn't so crucial here since the graphs look the same, but I'll refer to the first one because what it measures is more informative. From 1950 to 2008, there's a simple exponential decline in traffic deaths (r^2 = 0.97). As roads are made safer, as all sorts of car parts are made to boost safety, and as people become more familiar with traffic, we expect deaths to decline, and that's just what we see. I looked at earlier versions of the Stat Ab, and there is a similar exponential decline in railroad-related deaths from 1920 to 1959 -- again, probably due to improving the technology of railroads, trains, and so on. However, aside from the steady decline that we expect from safer machinery, there is a clear bulge away from the trend during the years 1961 - 1973. Although I haven't researched it, it seems impossible for roads to have went to shit during that time but not during the other times, or that cars made then were even less safe than the ones made before or after. The obvious answer is that people were just more reckless and/or hostile toward their fellow man in that period. There's no other huge departure from the trend, so if any time period has been characterized by "road rage," it was The Sixties (which lasted until 1973 or '74). Consider the age group whose brains are most hijacked by hormones, and maybe by drugs and alcohol too -- say, 15 to 21 year-olds. The oldest members of this group who were driving during the road rage peak were born in 1940, while the youngest ones were born in 1958. Hmmm, born from 1940 to 1958 -- Baby Boomers. (Those born after 1957 - 8, and before 1964, are not cultural Boomers.) And this doesn't seem to be an effect of lots more teenagers on the road than at other times -- there have been echo booms afterward and yet no big swings away from the trend. When the media and everyone hooked in to the media began talking about road rage 10 to 15 years ago, there was nothing new in the traffic death story -- indeed, the rate was continuing its decades-long decline. If you just want to know what is going on right now, the media may not be so bad at giving you that info. But this serves as yet another lesson to not believe anything they say, or imply, about trends unless there is a clear graph backing them up (or, in a pinch, a handful of data-points sprinkled throughout the prose). I located, collected, analyzed, and wrote up all of the relevant data -- stretching back nearly 60 years -- in less than one day, and only using the internet and Excel. This shows us again that journalists are either too clueless, too lazy, or too stupid to figure anything out. Labels: culture, Media, previous generations were more depraved, Technology

Friday, May 22, 2009

The Science of Fear, and some data on media overhyping of crime risks

posted by

agnostic @ 5/22/2009 02:10:00 AM

Since the world started falling apart, books on how crazy we are have never been more popular. Most focus on findings from behavior economics that show how human beings deviate from homo economicus in making decisions, and The Science of Fear by Daniel Gardner is no different. Unlike the others in this newly sexy genre, though, he doesn't look at economic decisions very much, but instead on how we assess risk -- sometimes to our own harm. Consider those who, in the panic after 9/11, switched from riding airplanes to the more dangerous mode of cars and died in car crashes.

I won't review the book at length since it's an easy read and well written -- worth adding to your "crazy fucking humans" summer reading list. For a taste, though, here's the author speaking on The Leonard Lopate Show. Gardner spends some time discussing how outta-whack the media coverage of a problem is with the underlying risk, as when silicone breast implants for awhile appeared to be the next cigarette or trans fat. Over at my personal blog, I put up two entries that have graphs showing, from 1981 to 2007, the per capita rates of homicide and forcible rape (risk), the fraction of all NYT articles that mentioned "murder" or "rape" (coverage), and the coverage-to-risk ratio (overhyping). Here's the homicide post and the rape post. In both cases, sometime in the early-mid 1990s, in the wake of a generalized hysteria -- identity politics, L.A. riots, Third Wave feminism, blaming AIDS on Regan, etc. -- the overhyping starts to take off and has remained high up through recent years. We've never been safer, yet we've only grown more paranoid. Labels: Behavioral Economics, crime, culture, Media, News

Sunday, April 01, 2007

|