|

Sunday, August 31, 2008

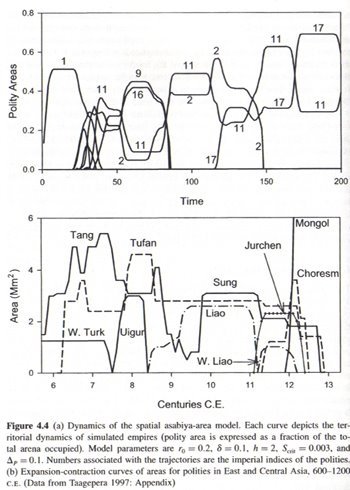

Variation is interesting. Why are there species, for example? Why do identical twins vary in life outcomes at all? How, and why, do the two antipodal maritime temperate regions of Eurasia, China and Europe, differ? The answers one comes up with vary by discipline and scope. In Farewell to Alms the economic historian Gregory Clark explains the genetic outcome of differences in lactase persistence (LP) as a function of variation in wealth; Europeans were wealthier so they could invest in the expensive production of milk and meat. I suspect most natural scientists would look to environmental constraints as the largest effect variables; LP arises in environments where cattle culture is more productive on a per area unit basis than grain culture. And then there is of course the fact that human lifestyles do not exist in a social and historical vacuum. There is evidence that wide swaths of the north China plain were abandoned by farmers during periods of political disorder due to their vulnerability to the depredations of nomadic groups (Genghis Khan's plan to depopulate the Yellow River plain and turn it into pasture was not as bizarre as one might think). When political stability returned there would be a shift in the boundary between nomad and farmer. If Peter Turchin is right then the variables effecting these changes are endogenous to a model of historical dynamics which are characterized by cycles (Turchin's case study of the expansion of Slavs and farming along the Ukrainian Cossack frontier is a classical case where politics rather than ecology served as the limiting reagent). Variation is interesting. Why are there species, for example? Why do identical twins vary in life outcomes at all? How, and why, do the two antipodal maritime temperate regions of Eurasia, China and Europe, differ? The answers one comes up with vary by discipline and scope. In Farewell to Alms the economic historian Gregory Clark explains the genetic outcome of differences in lactase persistence (LP) as a function of variation in wealth; Europeans were wealthier so they could invest in the expensive production of milk and meat. I suspect most natural scientists would look to environmental constraints as the largest effect variables; LP arises in environments where cattle culture is more productive on a per area unit basis than grain culture. And then there is of course the fact that human lifestyles do not exist in a social and historical vacuum. There is evidence that wide swaths of the north China plain were abandoned by farmers during periods of political disorder due to their vulnerability to the depredations of nomadic groups (Genghis Khan's plan to depopulate the Yellow River plain and turn it into pasture was not as bizarre as one might think). When political stability returned there would be a shift in the boundary between nomad and farmer. If Peter Turchin is right then the variables effecting these changes are endogenous to a model of historical dynamics which are characterized by cycles (Turchin's case study of the expansion of Slavs and farming along the Ukrainian Cossack frontier is a classical case where politics rather than ecology served as the limiting reagent).But for a moment I want to zoom the scale. In The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China, there is a chapter, The Riddle of Longevity: Why Zunhua?: People lived longer in the late-imperial department Zunhua in the mountains along the old Ming northern frontier...The expectation of life at birth for a woman was in the high forties, twice as long as in Jiaxing.... Jiaxing is highlighted because another chapter focuses on the taming of this region and its transition from being a marginal territory on the periphery of Chinese civilization to a rationally managed agricultural heartland. A case in point supporting the thesis of hydraulic despotism. The author notes a few points to contrast Zunhua and Jiaxing: 1) Climate. Zunhua was much colder in winter, with temperatures generally falling below zero. This surely dampened the local pathogen load. 2) Ecological differences. Zunhua is relatively mountainous, while Jiaxing is a coastal wetland region tamed into an expanse of intensive rice production. Irrigation is common in Jiaxing, but there were ecological constraints on its utilization in Zunhua (the soil is very sandy and so there are major issues with drainage which reduced the efficiency of canals). 3) Differences in diet. Zunhua's populace had a relatively diverse diet, where dry land agriculture was balanced with animal husbandry and hunting and gathering. In contrast, Jiaxing was a classic climax rice monoculture where almost all calories were from grain. 4) There were differences in ethnicity. The local historical identity of non-Han peoples was far stronger in Zunhua than in Jiaxing. The process of Sinicization had proceeded to completion in Jiaxing, which now lay along the axis of the economic heartland of China. In contrast, Zunhua was for nearly 3,000 years on the northeast boundary of Han habitation. It was known to the ancient Chinese, and Han populations were generally extant within its territory, but it was often dominated culturally by non-Han groups who would play a large role without Chinese history, culminating in the Manchus. The author also notes that there was a large difference in the extent of female labor in Jiaxing and Zunhua. It was a prominent feature of the life of peasants in Jiaxing, but not so of Zunhua. Additionally, one bureaucrat observed that unlike many other parts of China it was not typical for very poor women in Zunhua to supplement their income with de facto prostitution (random "walks" in the fields). The inhabitants of Zunhua were consumers of a fair amount of meat, but interesting they were also milk drinkers, atypical for China. The Census data from 1820 to 1910 suggests that Zunhua was relatively underpopulated (the author's focus here is on observations hinged around the late Imperial Manchu dynasty). This probably explains the relative wealth of a the typical peasant in Zunhua vis-a-vis one in Jiaxing (as well as lack of epidemics). But why was Zunhua so underpopulated in the first place? Are the data from the late Imperial period just a transient which captures a snapshot before the region is caught in a Malthusian Trap? To some extent I suspect so, but, I wanted to note specifically that Zunhua was on the radar of Chinese annalists nearly 3,000 years ago. Unlike vast regions of far southern inland China it was not new to Sinicization, rather, Sinicization simply never completed itself over the ensuing centuries. In fact, the region was for long periods under barbarian rule and outside of China proper. First, I want to repeat one of the major obvious insights of The Retreat of the Elephants, the process of Sinicization was inevitable, a matter of time, across much of what is today China. The millet and rice based agricultural systems associated with Han Chinese swept away competing lifestyles before them like a deterministic physical system. A proactive program of cutting down forests and clearing land, as well as channeling and controlling the flow of running water across the landscape, was part and parcel of the expansion of the Chinese state and Han identity. Some of the increase in the numbers of the latter is surely a matter of demographics, as Chinese settlers push into cleared land. On the other hand, there is extensive documentary evidence that those non-Chinese tribes which adhered to lifestyles which were at variance with that of the Han on many occasions adopted the intensive farming lifestyle when their territories were impinged upon. Eventually they saw themselves as Han. In the Christian and Islamic world it was common to assert that war against those outside of the bounds of their religious civilization was by nature just because they were infidels, and that enslavement of unbelievers was acceptable. Some of the material in this book highlights a similar ideology on the part of the the Han Chinese through their perception that those who were not Han were fundamentally not human or subhuman. But, just as with Christianity or Islam, tribes and peoples could become Han. This process was one less of ideology, though certainly elites adopted Confucian ethics and the Chinese classics, as opposed to one characterized by a way of life in terms of the optimal mode of resource extraction and utilization. To be Han the commoners farmed like the Han, and the rulers ruled like the Han. The Han way of life was eminently successful in terms of extracting more productivity per unit are of land, as evidenced by the fact that China is now well over 90% Han, and, its historically high population density. It was not a rigid orthodoxy, the original millet based farming system which arose around the Yellow River plain gave way to the dominance of rice agriculture, likely originally a feature of the culture of non-Han populations of central and south China. The Han way of life was one of maximal resource extraction and mass mobilization of populations under the aegis of a central governing unit. The transition from Han to non-Han seems to have been partly due to demic and cultural diffusion as a bottom-up process, but, as documented in The Retreat of the Elephants, it was also a function of the greater robusticity of the war machines of Han states. Not only could they mobilize more men, but they could they could organize and coordinate their actions because of the central nature of their polities. Local peoples had an advantage in terms of their knowledge of regional conditions and could wage a persistent rearguard action over the centuries by disrupting the social and agriculture systems (e.g., canals, bridges, bureaucrats, etc.) which Han society depended upon, but over the long haul Sinicization marched on. The machine could be broken, but never utterly destroyed. So why did Zunhua resist Sinicization so long? I suspect that the prevalence of animal husbandry indicates that the Han agricultural complex was simply not as well suited to this region. In areas too dry for agriculture irrigation is an option, but as noted above it was not an ideal one in Zunhua because of the characteristics of the terrain and soils. During the Former Han dynasty the emperor Wu engaged in a series of wars with the nomadic Xiongnu, but a serious problem with defeating these peoples was that a Chinese victory did not result in cultural assimilation. There were instances where the nomads could not win, but they could never truly lose. In areas too dry, cold and rugged for Han agricultural techniques nomadic life simply was more economically more efficient, or, more accurately the only option aside from hunting and gathering. The final Chinese "victory" over the Xiongnu occurred via co-option from their within by dividing their elite and brandishing the allure of civilized luxury goods. To some extent there was little difference in the material conditions of the Xiongnu elite, instead of engaging in raids to obtain wealth they were bribed or paid by the Chinese polity. In terms of efficiency this reduced the uncertainty on the part of the Chinese and so was economically a good decision as it allowed for a shift toward lower time preference. Reading the chapter in question here, I got the feeling that the economic and social conditions in Zunhua mimicked the contrasts which one might draw between pre-modern Europe and China. Europeans had a more mixed diet than the Asian peasant, and their agricultural complex relied to a far greater extent on animal husbandry and cattle (or, differently stated, more inputs of capital than labor to increase marginal returns). The average European peasants was arguably wealthier than the average Chinese peasant. In Farewell to Alms Greg Clark points to better hygiene in East Asia leading to a different death schedule, so that the Chinese would be pushing against the Malthusian limit to a greater extent (fewer mouths dividing up a finite pie in Europe vs. China at any given time). On the other hand, economic historians such as Raymond Crotty have emphasized the peculiar ecology of Northern Europe, and the incentives that existed toward raising of cattle stock as opposed to cereal agriculture. From what I have read it seems clear that in places such as Scandinavia traditional cereal agriculture gave a relatively low in yield. After all, wheat is a crop of the Mediterranean. Oats were a better bet, but are relatively unpalatable to humans, so they were more effectively grown as fodder for cattle. A quick look at a world map will show that Europe is far to the north of China. Because of the disparate impact of Westerlies the different sides of continents at the same latitude may experience climatic regimes which vary a great deal. Northern California and New Jersey are an example. Distance from oceans also matter, southern Nebraska has a more "continental" climate than either New Jersey or northern California despite similar latitudes. It seems to me that on reason China and Europe took such radically different paths in terms of agriculture styles, in particular northern Europe and China, were differences in their ecological parameters. Europe is a very high latitude temperate zone characterized by moderation in its climate and relative regularity in its precipitation. China is a relatively low latitude temperate zone because of its exposure to the winter air of central Asia, as well as being subject to the reversal monsoonal flow during the summer, which is the season of greatest precipitation. The region of Europe at the similar latitude as north China, the Mediterranean zone, is characterized by much milder temperatures in winter as well as an inverted precipitation regime from Asia, with a maximum during the cold season of least sunlight. But in the case of Zunhua ecology is probably not the only constraint. Its local population in the ancient phase included many "friendly" Xiongnu, suggesting its proximity to the steppe heartland. The period which The Retreat of the Elephants surveys is one of relative peace when Zunhua was not on a political frontier, the Manchu dynasty had subjugated Mongolia, and pushed the north boundaries of the Chinese Empire past the Amur river. For much of Chinese history in contrast Zunhua was a borderland, often not under Chinese hegemony. It seems plausible that therefore Zunhua was often a "No Man's Land," and so not subject to economic exploitation because of the risks inherent. I suspect an analogy to arable regions of Ukraine which were long occupied by nomads may be made. Up until the expansion of the Czarist state during the 17th century farmers that lived in central and eastern Ukraine would be subject to brutal exploitation by nomadic peoples, a dynamic one can glean as far back as the Scythians. Only with the rise of the Gunpowder Empires were the nomads on the marchlands finally defeated and extinguished as a threatening wild card which dissuaded farmers from settling vast swaths of Inner Eurasia. To some extent this might be interpreted simply as a variant of Greg Clark's point about shifting the death schedule; during periods when Zunhua was on the borders only those who were willing to risk life and limb would settle there, and periodic wars would "clean out" the region demographically. Ultimately though I am curious as to why agriculture developed the way it did in China, being so focused on human labor. In The Great Divergence it is pointed out that China was more densely populated than India, and that land was more plentiful in South Asia. In Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches it is argued that cattle reverence in India is a function of the fact that bulls are an essential draft animal (the author notes that a disproportionate number of feral cattle are cows). In When Histories Collide Raymond Crotty argues that cattle reverence in India is due to the fact that killing calves would be counterproductive in terms of milk production. I have already provided some general rationales for why animal husbandry was relatively rational in Europe. In China, the primary animal was the pig. In terms of domesticates it seems that the pig is nearly feral, generally subsisting on offal. The pig can not produce milk, nor can it serve as a work animal. Various regions of Eurasia developed "critical mass" as complex literate societies during the pre-modern era, but gross features of their modes of production still differed. Why? Some ideas. Going off William H. McNeill's arguments in Plagues and Peoples, I suggest that South Asia had a higher pathogen load than East Asia, and so there was always downward pressure on the population so that it did not "push" against the Malthusian Trap to the same extent. This also freed up more land so that successful farmers might get a relatively larger marginal return from the utilization of cattle as draft animals. In Europe the variables were not disease related, but structural differences in climatic regimes. Northern Europe was well watered, but extremely cool and moist. It was not suited to the arid adapted grains from the temperate zone because of the latter parameter, but also not appropriate for rice agricultural because of the former (the Po river valley has rice now due to advanced irrigation techniques). Mediterranean Europe is subject to the peculiarities of its winter maxima precipitation regime. This allows for the cultivation of olives and other specialty crops, but, it also results in a situation where most of the rain falls during the season of least sunlight. The ecological differences between Europe and China had an agricultural/economic implication: the Chinese could maximize caloric output per unit area of land through pure cereal cultivation. In contrast, the Europeans could not maximize calorie output through cereal cultivation but had to engage in "mixed" agriculture. The caloric total extractable out of the land per unit area was lower when summing the complements which were produced in European agriculture, but, the balance of nutritional intakes (protein, vitamins, etc.) was superior. This resulted in naturally greater physiological fitness for Europeans than Chinese as well as a lower final population density, and also natural evolutionary changes such as LP to deal with specific nutritional intakes. Finally, I want to touch upon the general manner in which farming spread. It is quite clear that over the long term in China the Han way of life resulted in reduced lifetime physiological fitness. Nevertheless, it was above the threshold of fitness necessary for viability so that an individual could reproduce. Additionally during the transient when it was expanding into regions where land was in surplus it might actually have been a lifestyle that lead to relative affluence. The main problem is that this affluence was temporary as the population reached the local Malthusian limit. At this point the exhaustion of the local ecological base which might have supplemented the grain monoculture was beyond a point of no return and the society was "boxed in" to a lifestyle predicated on surviving through the next harvest. Additionally, judging by the fact that Han elites had surplus which they could use to bribe barbarian warlords the quantitative rise in the subjects from which to extract rents was sufficient to more than cancel out the qualitative decline in the character of the tax extracted. The Han way of life might have been misery for the peasantry, but there was a reasonable case that the Confucian bureaucratic fixation on a free peasant base as the ideal subject population was self-interested. Underfed farmers made quiescent subordinates. In contrast, nomads were notoriously factious, and their periodic organized eruptions were contingent upon coalescence around a particularly charismatic figure, or, more often the collapse of the Chinese political order and the opportunity for unparalleled plunder. Nevertheless, the fact that nomads were presences along the northern edge of Chinese civilization implies that there were ecological constraints on the spread of the Han lifestyle. Beyond the reach of dryland farming and irrigation there was no possibility of settlement. While nomads could always turn arable land into pasturage, the Han could not always turn pasturage into arable land. Labels: China, Economics, History  On the heels of the previous paper describing the "genetic map of europe" comes a new paper that makes the same general observation that genetic data contain information about geography. These authors also develop a model that does reasonably well at predicting the country of origin of an individual based on genetics alone. On the heels of the previous paper describing the "genetic map of europe" comes a new paper that makes the same general observation that genetic data contain information about geography. These authors also develop a model that does reasonably well at predicting the country of origin of an individual based on genetics alone. It's worth considering why this is possible. A previous paper by some of these same authors proved that under a simple isolation by distance model, the first two principal components of genetic data are perpendicular in geographic space. So it appears that this basic model is a decent approximation to Europe; further work will likely refine the ways, which are likely to be interesting, that this model doesn't fit the data. The method the authors develop for predicting an individual's country of origin from genetics are only a beginning for this kind of application of genetic data. They note that the SNP chip used in the study only includes common variation, while rare variants are likely to be much more geographically restricted (and thus more informative in this kind of analysis). The limits to the resolution of these sorts of methods are likely to be very fine indeed; the authors note that, even with this panel, they're able to distinguish with some confidence individuals that are from the German, Italian, and French-speaking parts of Switzerland. With full resequencing data, it's likely that even the precise village of origin of an individual will be predictable from genetics alone. Labels: Genetics, Population genetics

Thursday, August 28, 2008

During the recent glut of genome-wide association studies, many researchers were compelled (or chose) not to make all their data public after publication due to vague privacy concerns. Instead, they often made available only genotype frequencies in sets of cases and controls, the idea being that individual-level information is lost when pooled together.

A new paper in PLoS Genetics shows that this assumption is wrong. The idea, obvious in retrospect, goes like this: assume some individual has genotype AA at a particular locus, while the frequency of A in the general population is 10% and the frequency in the pooled sample is 11%. This gives you some (very slight) amount of information suggesting that your individual is in the sample. If your individual is TT at another locus where the frequency of that allele is 25% in the general population and 27% in the pooled sample, this gives you another (again, tiny) bit of evidence that the individual is in the sample. Summing over thousands of loci, this actually becomes quite a bit of information. In fact, the authors are able to reliably tell whether an individual contributes DNA to a pooled sample, even if that contribution is around 0.1%. In theory, then, police with an unknown person's DNA could match it against all published case/control studies to find out if that person was involved in the study. A more immediate application could be to determine whether a suspect contributed DNA to a crime scene where the mixing of DNA (ie. blood) from a large number of individuals has muddied the forensic evidence. Labels: Genetics

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Update: Overcoming Bias responds.

Reading excerpts of the memoirs of the Mughal warlord Babur, founder of the dynasty in India, I note that his father was an alcoholic. This is not exceptional in the lineage, the Emperor Jahangir's reign was marred by problems due to his alcoholism. Nevertheless, these individuals were faithful Muslims by all their other actions. In fact, I have noted before that the early Arab Caliphs, who were responsible for the spread and dominance of Islam across what we now term the Islamic world, were by an large appreciators of wine. I was struck by Babur's mention of his father's weakness for alcoholism because I recently read about Glorious Revolution. As you know James II lost his throne because of his sincere Roman Catholicism. He rejected apostasy as the price of regaining his position. If his private correspondences did not attest to his sincerity, his public actions surely did. Nevertheless, despite James' relative religious seriousness and moral qualms for a ruler of his day (in contrast to his brother, Charles II), he retained his mistress as was customary for British kings. I point out these moral failings because I have always been struck by starkness of human hypocrisy and its incongruity in the face of avowed beliefs. How can a sincere Muslim drink alcohol? Have can a sincere Christian engage in sexual vice? One might infer from their actions that men such as James II were cynics, but as I note above James was willing to greatly reduce his chances of retaking his throne for the sake of his sincere religious commitment. I have been oversimplifying in reducing James' moral quandary to these two issues, contrasting the manifest evidence of his religious commitment in the face of inducements to convert to Protestantism with his sexual practices which contradicted Christian teaching. There are certainly other complicating factors, but I think the point stands that sin is common, and human weakness in the face of contradiction the norm. Mens' hearts are easily divided, and simultaneously sincere in their inclinations. All this leads to the point that I believe far too many of those of us who wish to comprehend human nature scientifically lack a basic grasp of it intuitively. I have never truly believed in an awesome God of history, so my hypothetical behavior in reaction to this transcendent truth is conjecture. I know how I believe I will behave, but I have no true intuitive grasp. Over the years I have come to the conclusion that many atheists simply lack a deep understanding of what drives people to be religious, and that our psychological model of those who believe in gods is extremely suspect. The "irrationality" and "contradiction" of human behavior may be rendered far more systematically coherent simply by adding more parameters into the model. Too many "rationalists" insist on the primacy of their own spare and minimalist axioms, while normal humans may lack both the eloquence and intuition to communicate to their "rationalist" interlocutors that they are missing key structural variables. When I engage with these sorts of issues with readers of Overcoming Bias or Singularitarians my suspicions beocme even stronger because I see in some individuals an even greater lack of fluency in normal cognition than my own. What I am lacking in becomes all the more obvious when I see with my own eyes those who are even more damned in the eyes of God. From all this one should not conclude that I see the reality of the mystical truths of gods before unveiled before my eyes. I do not. Rather, my point is that understanding human nature is not a matter of fitting humanity to our expectations and wishes, but modeling it as it is, whether one thinks that that nature is irrational or not within one's normative framework. Readers of this weblog are well aware and conscious of this issue; that is why I believe it is important to broach topics such as IQ because this variable matters, and most of us would wish that retardation was simply not a phenotype which was extant, but we know that that will not be so. Similarly, those of who are psychologically atypical enough to be rather obsessed with modeling human nature into a framework which is analytically tractable need to be more conscious of the alien complexities of the normal human mind, in all its baroque paradox. Labels: Psychology

An Association Analysis of Murine Anxiety Genes in Humans Implicates Novel Candidate Genes for Anxiety Disorders:

Specific alleles and haplotypes of six of the examined genes revealed some evidence for association (p ≤ .01). The most significant evidence for association with different anxiety disorder subtypes were: p = .0009 with ALAD (δ-aminolevulinate dehydratase) in social phobia, p = .009 with DYNLL2 (dynein light chain 2) in generalized anxiety disorder, and p = .004 with PSAP (prosaposin) in panic disorder. ScienceDaily: Furthermore, the team's international collaborators in Spain and the United States are trying to replicate these findings in their anxiety disorder datasets to see whether the genes identified by Finnish scientists predispose to anxiety disorders in other populations as well. Only by replicating the results firm conclusions can be drawn about the role of these genes in the predisposition to anxiety in more general. Haplotter shows selection around ALAD for Africans. PSAP is interesting: This gene encodes a highly conserved glycoprotein which is a precursor for 4 cleavage products: saposins A, B, C, and D. Each domain of the precursor protein is approximately 80 amino acid residues long with nearly identical placement of cysteine residues and glycosylation sites. Saposins A-D localize primarily to the lysosomal compartment where they facilitate the catabolism of glycosphingolipids with short oligosaccharide groups. The precursor protein exists both as a secretory protein and as an integral membrane protein and has neurotrophic activities. Mutations in this gene have been associated with Gaucher disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and metachromatic leukodystrophy.... Labels: Association, Finn baiting, Genomics

Tectonic environments of ancient civilizations in the eastern hemisphere:

The map distribution of ancient civilizations shows a remarkable correspondence with tectonic boundaries related to the southern margin of the Eurasian plate. Quantification of this observation shows that the association is indeed significant, and both historical records and archaeoseismological work show that these civilizations commonly suffered earthquake damage. Close association of ancient civilizations with tectonic activity seems to be a pattern of some kind. In the hope that dividing the civilizations into subsets might clarify the meaning of this relation, primary and derivative civilizations were compared. Derivative civilizations prove to be far more closely related to the tectonic boundaries. Similarly, the civilizations that endured the longest (and that have been described as most static) are systematically the farthest from plate boundaries. It is still unclear how the relation actually worked in ancient cultures, i.e., what aspects of tectonism promoted complexity. Linkages to water and other resources, trade (broadly construed), and societal response seem likely. Volcanism appears not to be involved.  ScienceNow, Did Rumbling Give Rise to Rome? has a nice map. Exogenous shocks playing a critical role in cultural creativity? Remember that earthquakes were often interpreted as negative divine omens and elicited a drive toward soul searching.... ScienceNow, Did Rumbling Give Rise to Rome? has a nice map. Exogenous shocks playing a critical role in cultural creativity? Remember that earthquakes were often interpreted as negative divine omens and elicited a drive toward soul searching....Labels: civilization, History

City of Brass is now at Beliefnet. I enjoy Crunchy Con, so it will have company on that domain in my RSS....

Medical Hypotheses, Figureheads, ghost-writers and quant bloggers:

The term 'quant blogger' (i.e. quantitative analysis blogger) was invented by Steve Sailer [8] who is the practicing 'blogfather' of an interconnected group of mostly pseudonymous bloggers that have been in some way inspired by Sailer's example and his (often distinctly 'non-PC') interests in issues such as IQ; immigration; evolution; education; politics and sports - often analyzed by sex, class and race. Sailer has blogged many interesting quantitative analyses, including an influential hypothesis of the relationship between 'affordable family formation' and politics in the USA. Labels: Blog

Sunday, August 24, 2008

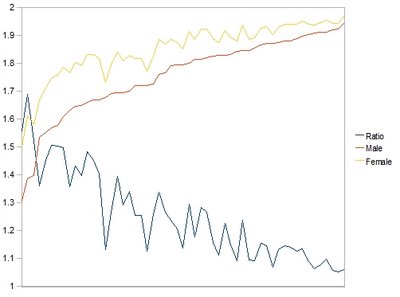

A few years ago Bryan Caplan argued that the cross-cultural male-female sex difference was due some innate differences. And specifically the differences he postulated explained why the less religious a society was the greater the sex difference. I took data from Rodney Stark's original paper (N = 54 nations), log-transformed the proportions of males and females who claimed to be religious, and plotted them along with the sex ratio (sorted by increasing male religiosity from left to right). As you can plainly see, the trends converge as the societies become progressively more religious and the sex ratio attenuates. Full disclosure, I discarded China from the list of nations because it was such an outlier of irreligiosity compared to every other nation and I didn't want to change the scaling too much. Stark has a follow up paper which explores this pattern of greater sex differences in religiosity with decreased traditionalism in the social milieu. A few years ago Bryan Caplan argued that the cross-cultural male-female sex difference was due some innate differences. And specifically the differences he postulated explained why the less religious a society was the greater the sex difference. I took data from Rodney Stark's original paper (N = 54 nations), log-transformed the proportions of males and females who claimed to be religious, and plotted them along with the sex ratio (sorted by increasing male religiosity from left to right). As you can plainly see, the trends converge as the societies become progressively more religious and the sex ratio attenuates. Full disclosure, I discarded China from the list of nations because it was such an outlier of irreligiosity compared to every other nation and I didn't want to change the scaling too much. Stark has a follow up paper which explores this pattern of greater sex differences in religiosity with decreased traditionalism in the social milieu.As Bryan notes Stark has his own particular model for why this sex difference persists. I have some issues in the details with Bryan's hypotheses, but I think he's going in the right direction. That being said, I wonder if some of the differences across societies might be viewed through individual vs. group dynamics. In societies where religions are personal choices, and "switching" or "defecting" does not entail high costs, then it is rational to "shop around" for the best bundle of characteristics which are congenial to your own preferences (or, one can opt-out of the whole institution). Some sort of neoclassical inspired rational choice model might work very well in these societies; the United States is probably one such culture (about 16% of Americans "switch" in their lifetime according to the Religious Identification Survey). But a society like Saudi Arabia or even Italy is far less of a rational individualist utopia; traditional religions operate like monopolies and there are powerful group level pressures to conform at the expense of personal actualization. Men and women have the same cognitive biases, but they're channeled and express in very different ways. Finally, I was curious as to insights from the Pew Religious Landscape Survey. Trends were hard to spot; whatever group level effects I'm alluding to might be extant only on the scale of national cultures. But, I did notice that when there were two Protestant denominations which split on liberal-conservative lines, such as the American and Southern Baptists, or the Presbyterian Church in America and Presbyterian Church USA, the conservative denomination had proportionately more males. One hypothesis might be that the constraints, or disincentives via social sanction and ostracism, are low enough in the more liberal sects that they suffer high male defection rates vis-a-vis their conservative counterparts. Unfortunately the N for the GSS to answer these questions just isn't there, so I'll have to dig elsewhere.... Labels: Religion

One thing I have wondered about: why do people want to give people the benefit of the doubt in terms of looks if they get a "Myspace angle" photo or only hear someone's voice? I have talked to many friends who are really biased in the direction of giving people the benefit of the doubt about the reality that there is a strong incentive to select the flattering picture (in large part because of retarded individuals such as my friends). So the individual is going to be less attractive than their photo on average even if it isn't a totally blurry or tiny image. Additionally, in terms of pure perception I notice that when you see a very small thumbnail size photo there's a tendency to perceive the person as more attractive than they are when you click the image and see them at a higher resolution. Finally, many people easily create a fantasy image of someone based on their voice.

So what's up with this? Why aren't we preprogrammed to be choosier and more jaded about these things? False negatives are less harmful than false positives? Why are guys still surprised when they meet their Myspace date who never posted a fully body shot and notice that the height to width ratio isn't what they'd prefer? Is it the whole polygyny thing? Are women any different?

Saturday, August 23, 2008

Frequency-Dependent Selection and the Evolution of Assortative Mating:

A long-standing goal in evolutionary biology is to identify the conditions that promote the evolution of reproductive isolation and speciation...Here, we analyze the conditions under which selection favors the evolution of assortative mating...using a general model of selection, which allows fitness to be frequency dependent. Our analytical results are based on a two-locus diploid model, with one locus altering the trait under selection and the other locus controlling the strength of assortment...Examining both equilibrium and nonequilibrium scenarios, we demonstrate that whenever heterozygotes are less fit, on average, than homozygotes at the trait locus, indirect selection for assortative mating is generated. While costs of assortative mating hinder the evolution of reproductive isolation, they do not prevent it unless they are sufficiently great. Assortative mating that arises because individuals mate within groups...is most conducive to the evolution of complete assortative mating from random mating. Assortative mating based on female preferences is more restrictive, because the resulting sexual selection can lead to loss of the trait polymorphism and cause the relative fitness of heterozygotes to rise above homozygotes, eliminating the force favoring assortment. When assortative mating is already prevalent, however, sexual selection can itself cause low heterozygous fitness, promoting the evolution of complete reproductive isolation...regardless of the form of natural selection. I think sexual selection is real. Even the more "wild" forms of this, such as the Handicap Principle, have been theoretically (formally that is) and empirically supported in some circumstances. That being said, too much sexual selection, like stochastic forces in general, emerges as a deus ex machina in lieu of a plain admission of ignorance. The question is not does sexual selection occur, but in what contexts and frequencies.... Labels: Genetics

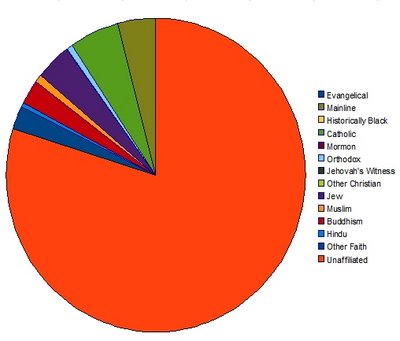

Just noticed something weird. Seems like around 20% of atheists in the United States self-identify as a member of a religion. By atheist, I mean someone who states that they "Do not believe in God." 19% of Buddhists are atheists. 10% of Jews. 5% of Muslims and Hindus. 9% of "Other Faiths." And of course, 22% of the Unaffiliated (those without a religious identification). To get to my 20% number I just went to the Pew US Religious Landscape Survey, checked belief in God by religion and cross-referenced with the proportion within the sample of each religion. I think it's a rather peculiar situation that the same proportion of atheists are religious as non-religious are atheists! Chart and data below the fold....

Labels: Religion

Thursday, August 21, 2008

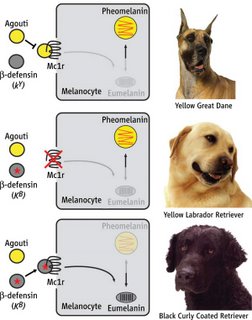

Reading up on the MC1R, I came across this nice summary of work I mentioned before on the genetics of coat color in the dog. The summary includes the figure below, which is a pretty intuitive illustration of a few of the genes involved in pigment type-switching (ie. production of eumelanin versus pheomelanin). The caption:

Production of yellow versus black pigment in dogs is controlled by three genes: Mc1r, Agouti, and CBD103. Dogs carrying wild-type alleles for all three genes have a yellow coat resulting from Agouti antagonism of Mc1r signaling in melanocytes (yellow Great Dane, top). Dogs carrying a loss-of-function mutation at Mc1r have a yellow coat, regardless of their genotype at Agouti or CBD103 (yellow Labrador Retriever, middle). Dogs carrying wild-type alleles for Mc1r and Agouti, together with the dominant black allele of CBD103 (KB) have a black coat resulting from the interaction between a beta-defensin and Mc1r (black Curly Coated Retriever, bottom).  Labels: Genetics, Pigmentation

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

In the spirit of the games, Daniel MacArthur has an extensive post up on ACTN3 and the genetic endowments of elite sprinters. Well worth a read.

Labels: Genetics

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

The first correct daily temperature forecast was not broadcast [in China] until July 1999. Previously, temperature predictions were never permitted to fall outside the range for efficient factory work. That's from Cultures Merging: A Historical and Economic Critique of Culture, by Eric Jones. Jones is best known for his book The European Miracle, an anti-Pomeranz text if there ever was one. In Cultures Merging, he provides decent anecdotal evidence that while "bad culture" might be able to hold back a country back a little, cultures are actually fairly fluid over the span of decades, and tend to steer in the direction of economic efficiency (a point emphasized by Clark). Jones's pet example is East Asia, where Confucianism was once said to be a barrier to economic development (too much blind obedience to the dead hand of hierarchy) but is now lauded as the driving force behind superior "Asian Values" of hard work and sacrifice. The first half of the book (parts one and two of four total) can be easily recommended to those interested in the culture question. Lots of stories, some big-think, some bold generalizations. The second half is filled with stories about his Asian graduate students; not sure what that's all about. But while it's fun to read books about culture, it sure would be nice to bring some rigor to the debate, wouldn't it? My preference--typical for an economist--is to look for the key under the lamppost of things we can actually measure. Lynn and Vanhanen's national average IQ measures spring to mind--and boy are those scores ever robust as predictors of national economic outcomes. And Jones and Schneider show that even if you control for "cultural" variables like Confucianism, Islam, or Buddhism, the nation's average IQ is still a strong predictor of economic performance. High-IQ groups are likely to have some good cultural traits like patience, cooperativeness, and a tendency to agree with economists on the merits of untrammeled competition. What'd be nice to know at this point is "What's left after you control for national average IQ?" Do cultural variables (as measured in, say, the World Values Survey) still have predictive power? It might be all stems and seeds, but right now we don't know. Sure would be nice if someone out there did some research into this....

Debin Ma of the London School of Economics has spent time in the archives and has come to conclusions quite different from Pomeranz's.

Ma's recent papers (especially this one and this one) make archive-driven comparisons of European and East Asian living standards around the start of the industrial revolution. Both papers have coauthors, but I focus on Ma because he speaks and reads both Japanese and Chinese, something lamentably rare among economic historians at English-speaking universities. One quote from the abstract of the first-linked paper: Matching caloric and protein contents in our Japanese consumption baskets with those in European baskets, we compare Japanese and European urban real wages. Real wage rates in Kyoto and later Tokyo are about a third London wages but comparable to wages in major Southern and Central European cities for the 1700-1900 [period]. From the abstract of the second-linked paper: In the eighteenth century, the real income of building workers in Asia was similar to that of workers in the backward parts of Europe and far behind that of workers in the leading economies in northwestern Europe. Industrialization led to rising real wages in Europe and Japan. Real wages declined in China in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.... A lot of Ma's work is Japan v. China, not Asia v. Europe, so both lines of his agenda are likely of interest to GNXP readers. Given the overfishing in the pool of English-language economic history documents, Ma should be able to just throw his net overboard and pull in the big hauls for at least another decade.

Monday, August 18, 2008

Asia finally getting in on the genome-wide association game?

posted by

p-ter @ 8/18/2008 07:25:00 PM

Nature Genetics has reports from two Japanese groups on an association between variants in KCNQ1 and susceptibility to Type II diabetes. The study itself falls into the now-standard genome-wide association study mold (except perhaps for the choice of SNPs in one of the studies--"only" 100,000, mostly genic--and the decision to not type them using a chip), but performing GWA studies in non-European populations is important for a number of reasons:

1. It enables the identification of novel loci involved in a trait. In some idealized model, risk for a disease could hypothetically be influenced by a set of N genes, but in a population polymorphic at only some subset of those genes, only that subset will be found by association studies (which map variation--if there's no variation, an association study won't find anything). Due to the vagaries of genetic drift (and perhaps natural selection), different populations may end up polymorphic at a different subset of those genes. So mapping the same trait in a number of distant populations could lead to a much greater understanding of the biology of the trait. Even if it's not the case that one population has variation in a gene and another population doesn't, it's certainly the case that the power to detect a given variant can differ between populations due to smaller variations in allele frequency. That seems to be the case here--the SNP identified is at low frequency in European populations (~5% minor allele frequency), but at modest frequency in East Asians (~40% MAF), right in the "sweet spot" for detection by an association study. 2. Studies of the same phenotype in multiple populations also allows one to get at questions of "heterogeneity". Back in the old days of candidate gene approaches to complex disease, the failure to replicate an association was often blamed on heterogeneity, ie. the possibility that the risk alleles in your population were different from the risk alleles in the population in which the association was originally found. That excuse always seemed to be a bit suspect, and now, with sample sizes orders of magnitude greater, it's testable. In this case, the risk allele in the Japanese sample is replicated in a Danish populations, suggesting heterogeneity (and effects of genetic background) are not an issue in this instance. Labels: Genetics

Sunday, August 17, 2008

In many vertebrates, there is an association between pigmentation and behavior. One potential reason for this is that genes influencing pigmentation also have pleiotropic effects on other traits, including behavior. A recent paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution lays out this hypothesis:

In vertebrates, melanin-based coloration is often associated with variation in physiological and behavioural traits. We propose that this association stems from pleiotropic effects of the genes regulating the synthesis of brown to black eumelanin. The most important regulators are the melanocortin 1 receptor and its ligands, the melanocortin agonists and the agouti-signalling protein antagonist. On the basis of the physiological and behavioural functions of the melanocortins, we predict five categories of traits correlated with melanin-based coloration. A review of the literature indeed reveals that, as predicted, darker wild vertebrates are more aggressive, sexually active and resistant to stress than lighter individuals. Pleiotropic effects of the melanocortins might thus account for the widespread covariance between melanin-based coloration and other phenotypic traits in vertebrates. This is clearly far from gospel truth; the authors are laying out the plausibility of this hypothesis and a framework for further exploration. The hypothesis is that higher levels of the molecules that bind the melanocortin receptors (the melanocortins and agouti proteins) lead to both darker pigmentation as well as pleiotropic effects in other tissues (I've mentioned before some of the effects of messing with these receptors in sexual behavior and metabolism). Analysis of the way pigmentation and various other traits vary in mouse models leads to results consistent with this hypothesis. A corollary of this argument is that in vertebrates where pigmentation is controlled downstream of the melanocortins (ie. at, or further downstream of, MC1R), this correlation between pigmentation and other traits should not be consistently true. For this reason, the authors argue that humans should be exempt. However, they may be unaware that some difference in pigmentation both between and within populations is controlled by ASIP, a protein that binds MC1R, acting as an antagonsist for melanocortin binding. Humans, then, could be an ideal test case for the hypothesis--do phenotypes like aggression map to ASIP like pigmentation does? However, the unpalatable nature of this question makes it rather unlikely to be pursued in humans. Labels: Genetics, Pigmentation

Excellent new physics blog, Built on Facts. Highly recommended, though the author of the weblog seems to be a big believer in the omnipresence of porn (perhaps building upon personal facts?).

Saturday, August 16, 2008

Svante Paabo's group just finished sequencing the complete mitochondrial DNA of a Neanderthal. The article is in the newest Cell. John Hawks has a summary.

One of the big findings: In one tiny way, we've become more like monkeys recently, since Neanderthals, chimps, and other sequenced apes have the same non-homo-sapiens variants on COX2, but these human variants are common among old world monkeys. Guess I'll have to take my pet macaque off of Vioxx now. Upshot: Something big may have happened to human metabolism in the last few hundred thousand years since our split from the Neanderthals. And on this one gene, the solution our species found looks like the same solution that works for monkeys.

Friday, August 15, 2008

Finally: A book on standardized testing your hippie girlfriend will enjoy

posted by

Herrick @ 8/15/2008 10:50:00 PM

Daniel Koretz of Harvard's Graduate School of Education took the lecture notes from his course, "Methods of Educational Measurement," and turned it into a book: Measuring Up: What Educational Testing Really Tells Us. It's readable, filled with funny anecdotes, and contains absolutely nothing that will be new to regular GNXP readers.

But because Koretz takes the math and most of the controversy out of the debate over standardized tests, he has time to actually drill home a couple of important points repeatedly: Modern standardized tests have little bias, are pretty reliable, and while they don't tell you everything about a person or a school or a city, they are good for making rough predictions. Hence, the title of this blog post: Feel free to recommend Measuring Up as a "baby steps" book for your favorite sociologist or folk guitarist. Koretz waves his political correctness card early on, letting us know that "IQ [is] just one type of score on one type of standardized test..." and he lets us know about the "pernicious and unfounded view that differences in test scores between racial and ethnic groups are biologically determined." But you already knew he was going to say that, right? And in an unintended parody of blank-slatism, he has a chapter entitled "What influences test scores" that never once mentions genetic factors, even to dismiss them. Koretz does a great job dodging such troubling questions while focusing on what he really wants to talk about, with solid, candid chapters entitled "Validity," "Inflated Test Scores," "Error and Reliability," chapters that actually do a good job of conveying big ideas about non-experimental social science in jargon-free prose. Kudos to him for doing so. Treat it as a book on the narrow field of psychometrics and its link to policy, not as a book on the broader field of standardized tests per se and its link to policy: You'll spend a lot less time grinding your teeth. Labels: Psychology

Thursday, August 14, 2008

A rumor I've been hearing a lot lately, although I recall hearing it as early as 2003, is that "porn is becoming / has become mainstream" -- or that it's ubiquitous, unavoidable, the wallpaper of our culture. Like most alarmist ideas spread by the innumerate -- failing schools, oral sex rampant among teenagers, the coming Islamic Caliphate -- I assume it is a gross exaggeration or false. And as always, I'm right. It doesn't take a genius: simply judge based on the track record of similar panics made possible by mass media, going back to the witch hysterias of Early Modern Europe.

I collected a bunch of data about a month ago and planned on doing some time series analysis, maybe showing how certain models (like epidemics or logistic growth) would fit the data, but the fall semester begins soon, and I'm preparing enough as it is. So nuts to the analysis; I'll just present the data, since the picture is very clear. In brief, the popularity of pornographic movies has remained steady for over 20 years, and in a sense for the last 35 years -- when the data begin. The popularity of print pornography fell sharply after its peak in the early/mid 1970s and has more slowly declined for about the past 20 years. Even non-pornographic but racy "lad mags" have seen their popularity tank, with only Maxim US holding steady. Before getting to the data, though, how far back does the "porn has become mainstream" meme go? I didn't conduct an exhaustive search, but I found a 1990 letter-to-the-editor in the NYT, as well as a 1998 news story in Time, so it's hardly new. It's interesting to note that most such articles feature a quote like this one from New York Magazine in 2003: Over beers recently, a 26-year-old businessman friend shocked me by casually remarking, "Dude, all of my friends are so obsessed with Internet porn that they can't sleep with their girlfriends unless they act like porn stars." The grave implication is: "Just think of what young people who grow up with this will expect!" But a moment's reflection tells us that the same is true of men who visit prostitutes, who've been around forever. And yet men haven't come to expect their wives to behave like wild whores inside or outside the bedroom -- again, except for the handful of 20-something losers who New York Magazine manages to mine such embarrassing quotes from. Indeed, the universal Madonna / Whore dichotomy tells us that most men will continue to prefer their flings to act like call girls, pornstars, strippers, etc., while preferring their gfs and wives to act not whorish. Enough gasbaggery; onto the data (and then more hot air). The "porn is everywhere" meme claims that a high percentage of people are infected by porn, whether through video or print. Obviously the claim is not that there's a lot of porn out there, but which no one ever consumes -- so we just look at the prevalence of porn-watchers over time. Fortunately, the General Social Survey, a large and representative national survey, asks Americans if they've watched an X-rated movie in the past year. To see for yourself, go here and type in, without quotes, "xmovie" in the row box and "year" in the column box. If you want to see male vs. female, type "sex(1)" for male or "sex(2)" for female into the selection filter box. Across the years, the response rate is 58%, from about 51,000 people -- damn good for surveys. Here are the results for men and women (click on the image to see it full-size): For men, porn-watching declined at least from 1973 until 1980, and increased until 1987. After that, you may be able to see fluctuations up and down but they're around a pretty steady value of about 35%. The pattern for women is much clearer to see: essentially no trend, but cycles of varying period and amplitude. I interpret these patterns as a decline during the 1970s when porn theaters became unfashionable, an increase during the 1980s as porn became available on VHS, and no change afterward -- in particular, no skyrocket due to the availability of internet porn, something I would not have predicted by intuition. Also bear in mind that if porn were indeed "becoming more mainstream," we should see a strong upward trend just because people are less embarrassed to admit they watch it. Only if people in the 1970s were hooked up to porn 24 hours a day but denying it, while people today admit to it at the same rate but are watching less, would we observe a lack of a strong upward trend. Even in that case, that means porn-watching was more prevalent in the past. I favor a simpler interpretation: that because porn has not become mainstream, nor more taboo, people tell the truth at the same rates from the sexually liberated 1970s up to today. There are of course liars, but they don't seem concentrated in one period or another. How bad is the lying in any period, though? -- maybe all men are watching porn now but only 35% admit it. In 2003, the Nielsen Ratings people tracked the traffic of internet porn sites, and they found that 1 in 4 internet users visits porn sites (see here). That's just what we'd expect from the GSS results, which show that of men and women combined, 24% in 2002 and 26% in 2004 watched porn. Traffic doesn't lie, and because the numbers are virtually identical to what people say, we conclude that almost nobody lies about watching porn (at least in anonymous surveys). So not only have their proportions not increased relative to before, but porn-watchers are not even a majority of men -- a bit more than one-third. For women, even less so -- about one-sixth. Porn is not now, and never was, mainstream. Turning to porn in print, I collected circulation data for Playboy for any year I could find. The data are from many sources -- business sections of newspapers, histories of the magazine, etc. -- and for some years I couldn't find estimates. Still, there are plenty to see a clear pattern. I did the same for Maxim's US edition, both shown here: Playboy accelerated in popularity from its beginning in 1953 to 1973, after which it plummets until 1987, and then it slowly but steadily declines to today. I don't have rich data to show it, but from what I read in my research, the same rough pattern holds for other porn magazines like Penthouse and Hustler. Maxim looks like it's grown logistically, on analogy with a fad growing by word-of-mouth contagion. Maxim of course is not porn; the nearest thing might be 1940s pin-ups. I speculate that Playboy's exponential growth was due to featuring young brunette girl-next-door types, and its crash due to using blonder and older "power bitch" types. Maxim has done well, in this view, for relying so heavily on dark-haired women. In any event, we see that porn has not become mainstream in print either -- just the opposite. One last batch of data mostly from the UK, home of the "lad mag." Almost as soon as the fad had begun, it peaked and began plummeting, which has been well covered in the British press. I've shown it here for three of the most popular UK lad mags (I culled the data from various newspaper or other reports): The US edition of FHM appeared to be doing well, even if it had begun to saturate. The drop-off I drew to show that it was abruptly canceled and only exists as a website now. Stuff Magazine, also once popular in the US, was cancelled in 2007. So even the non-porn but racy lad mags are dying off, save Maxim US. Because the "porn has become mainstream" meme is part of a panic -- either about eroding cultural standards, eroding barriers between public and private vis-a-vis sex, eroding relations between men and women due to unrealistic expectations, or the erosion of something else -- most of those who already believe it will not be persuaded by the stark clarity of the data here. (Hopefully the open-minded ones will end up reading this.) Like witch-hunters, they will shift the goalposts perhaps by saying, "Well yeah, but that just means that porn's influence is more subtle and covert, but no less pervasive and corrupting because of that." The first target will be female appearance, of course: as porn becomes more ubiquitous, they start dressing like sluts! Except that porn-watching increased most dramatically and reached a peak during the '80s -- the decade of high-waisted pants, granny-panties, and bulky manlike tops (baggy sweaters, shoulder-pads, etc.). I've written elsewhere about how girls don't even dress like sluts anymore, a 5-year fad in thongs notwithstanding. The second target will be sexual behavior: as porn becomes more ubiquitous, people will begin acting more promiscuously. But I've already shown that there was probably a single increase and single decrease in promiscuity, with the turning point around 1991. The popularity of porn either waxes and wanes for women or dips, increases and stays for men -- it has nothing to do with how promiscuous people are. Anyway, I could go on, but you get the idea. Let's all be done with this "porn has become mainstream" nonsense. Labels: babes and hunks, culture, GSS, porn

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

A little while back, I mentioned a paper demonstrating the rapid evolution of a gene duplicate as it was selected for targeting to a novel subcellular location. The same group has apparently been following up a number of these stories--see this new paper on another example of a retrocopy of a gene acquiring a novel subcellular localization via positive selection in hominids.

Labels: Genetics

Most of you have heard about the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation (which, more accurately should probably be termed the Catholic Reformation). But after posting earlier on the parameters which affect the shape and constraints of religious change, I thought it was important to mention something: in the second half the 16th century Catholicism was very close to becoming purely a Mediterranean sect of Christianity. In other words, Catholicism seemed on the verge of disappearing from Germany to the same extent that it did from England by and large. In East Central Europe, the precursors to the modern states of the Czech and Slovak Republics, Poland and Hungary, it was also being marginalized by Lutheranism, the Reformed Churches as well as even more extreme groups such as Unitarians. France had a large Huguenot minority which was represented disproportionately among the gentry and nobility. If you want to read about the extent of the rollback in the face of Protestantism check out The Thirty Years' War, The Reformation and Divided by Faith. All of them explore the massive penetration and domination of Protestantism among the Polish and Austrian nobility and the near collapse of Catholic parishes in regions which we today view as staunchly Roman Catholic.

But a Catholic world dominated by the peninsular Mediterranean never became. Today we have a German Pope, and the previous Pontif was Polish. Vast swaths of southern and western Germany remain Catholic, while the Protestant minority in France was expelled in the later 17th century (aside from mountainous redoubts such as Cevannes). What happened? The short answer is that the Hapsburgs happened. The Church operated in concert with the Holy Roman Emperor and other monarchs to reinvigorate the institutional framework of Roman Catholicism. The Jesuits were famously instrumental in this process of reform. But this was not a pure program of persuasion; Protestants who were not noble were often given the choice of emigration or conversion to the Catholic faith. Whole districts in Austria where Catholic parishes were no longer a feature of the landscape were re-Catholicized in a few years simply through imperial fiat. The mostly Protestant nobility could not be forced to convert, but they were blocked from patronage and access to the offices which brought glory upon their houses and maintained their fortunes. Additionally, though their private worship was given some latitude on their estates initially a step-by-step process of removal of these privileges also occurred over several generations. The result was that noble lineages who remained in the re-Catholicized regions of the Hapsburg Empire converted to the established religion, while those who would not give up their Protestant faith emigrated to regions where they could practice freely. There are two domains of the former Hapsburg Empire which retain a large Protestant population; Hungary and Transylvania. And they illustrate the power of imperial fiat in driving religious change, because for much of the early modern period Transylvania was under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. Hungary was divided by a western Hapsburg domain and an eastern Ottoman portion. Not surprisingly, it is in the east that Protestant populations are most numerous because it is in the east that the re-Catholicization program was operative for the shortest period since these regions were under Turkish rule for most of the 17th century. The moral of the story here is that the diplomatic history of Europe between 1600 and 1800 can very accurately predict the religious configuration that we see today. Mass social movements simply could not succeed without the support of the elite, and the potentate had wide powers with which he or she could reshape that elite.

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

Another dopamine-related fear and anxiety related gene, COMT Genetic Variation Affects Fear Processing: Psychophysiological Evidence. ScienceDaily with the predigested form. Quick points, Another dopamine-related fear and anxiety related gene, COMT Genetic Variation Affects Fear Processing: Psychophysiological Evidence. ScienceDaily with the predigested form. Quick points,1) It looks like the SNP in question does show some variation world wide. Europeans seem to have a higher frequency of the MET/MET genotype than Africans, while Asians tend to be lowest. 2) I notice that some genes around this locus show up as being under selection in Haplotter. Within +/- 1.5 megabases. 3) This locus is implicated in a lot of other stuff. 4) Genetic Future's post The challenge of psychiatric genetics is probably worth a read if you are interested in these findings. I don't have much original to say here that I/we haven't said before. So I invite you to browse the links below.... Related: Optimal personality and way of life, Really ancient morphs?, DRD4, politics & friendship, Heritability of the Ultimatum Game, DRD4, sex and Jews, More DRD4, ADHD & DRD4 and Picking apart the black box. Labels: Genetics

Attractiveness: logarithmically perceived, normally distributed, sought for genetic benefits

posted by

agnostic @ 8/12/2008 02:46:00 AM

Our intuition of space and time is to perceive them logarithmically: we place a bunch of tick-marks near "here" and "now," and only measure orders of magnitude as we move outward. The linear scale used by scientists places a tick-mark at evenly spaced intervals. For example, between "here" and 100 miles away, humans may have a bunch of words for nearby distances -- "right here right here," "right here," "heeeeere," "here," and "there" -- while we would represent the majority of the distance that is not near with a few words, such as "theeeeere," "over there," "way over there," "way way over there," etc. Ditto for time. John Hawks reviewed a recent study, which itself contains many references, er, right here right here.

I think we perceive physical attractiveness in the same way. (Although quick Googling didn't turn up anything, I'd be surprised if this idea were original -- at least, it's not a common idea.) The reason is the same as the above: when we use something like the popular "1 to 10" ratings, we seem to finely slice up the attractiveness space near the "good-looking" end and place tick-marks increasingly farther apart as we move farther away, like this: Just think about it -- have you ever split hairs over how incredibly ugly a person was, like 1 vs. 2? Probably you have never done so, but I'll bet you and your friends get into regular arguments about whether Jessica Alba, or anyone else like her, is an 8.5, 9, or 9.5. You probably save the "1" from the "1 to 10" scale only for the most distant monsters, humanoids so freakish you could not expect to reach them in a dozen lifetimes. And anyone in a large vicinity of that spot would be compressed into the "1" category. Why do we make these compressions -- why not keep the fine structure of the space, like rate people from 1 to 1 million? Because we have limited vocabularies and cognitive resources, and because not all regions of the space are as attention-worthy as others for surviving and reproducing. We care a lot about what's going on near us because the goings-on of the other side of the world, until very recently, had no bearing on our survival and reproduction. The same is true for time: until very recently, the very long run did not matter at all, so why bother measuring the next millenium in yearly intervals? Only the somewhat near future has mattered. Continuing the analogy, then, it must be that it has been the good-looking rather than the ugly people who have been most worthy of our attention during our evolution, since that's where the density of tick-marks is greatest. That is not a tautology. Indeed, the great evolutionary biologist William Hamilton had an idea that probably is too crazy to be true -- that animals pay attention to attractiveness in order to avoid getting infected by parasites while mating, attractiveness signaling the mate's parasite-free status and ugliness signaling their being bug-ridden. But if that were true for humans (and I'm only talking about us now), then we would finely slice up the attractiveness space near the ugly end, reflecting our worry of getting infected: "definitely swimming in bugs," "pretty buggy," "buggy enough that I'll be scarred for life," "buggy but I won't be too compromised by sleeping with them," "low bugginess," etc., and compress the vast expanse of attractive people into a few categories like "probably not buggy" and "definitely safe." So, it doesn't look like we avoid the ugly but that we pursue the attractive, and that jibes better with the alternatives to Hamilton's "parasite avoidance" hypothesis, namely the genetic hypotheses. First is Alfred Russell Wallace's "good genes" hypothesis: we pursue good-looking people because their good looks signal having genes that have protected them against the ravages of pathogens, or whatever else may damage their health. And second is R.A. Fisher's "sexy sons" hypothesis: we pursue good-looking people because, whether we find them good-looking or not, the potential mates of our offspring will, so we'd improve their reproductive success by giving them genes for attractiveness. The idea that attractiveness is logarithmically perceived doesn't decide between these two genetic theories, but I think it does go against the "parasite avoidance" hypothesis. Last, I used to think that attractiveness was lognormally distributed -- that, due to the synergistic effects of different body parts, most people are ugly, and only a handful are good-looking. (And anyone who says otherwise is being polite, fooling themselves, or not looking at a broad spectrum of human beings.) However, that's just based on my perception -- perhaps attractiveness really is normally distributed. If our mind re-scales attractiveness using logarithms, then it will transform a normal into a lognormal distribution too. Normally distributed traits suggest an additive genetic basis, whereby small effects across a large number of loci are added together to determine the phenotype.* A lognormally distributed trait, such as "genius" in the sense of "eminence in the arts and sciences," has low heritability. The reason isn't relevant here; what's important is that we wouldn't expect a lognormally distributed trait to have a mostly additive genetic basis. But the one study that estimated the heritability of attractiveness, McGovern et al. (1996), found that the monozygous concordance rate was virtually twice the dizygous rate (0.65 vs. 0.33, respectively), and that means that the genetic variance in the trait is almost entirely additive. So the quantitative genetic evidence fits into the bigger picture of a normally distributed trait in reality, but which the human mind transforms logarithmically. I can't do any empirical tests like those in the study that John Hawks reviewed because we haven't yet found an objective way to measure attractiveness. I don't just mean that we can't trust what people say -- even if you measured a person's attractiveness by taking the average level of physiological arousal from subjects who viewed the person's picture, that still is a reflection of the subjects' perception. However, I'm more of a theorist than an experimentalist, so maybe a clever doohicky-rigger out there can think of something better. If they do, the prediction is that true attractiveness can be measured on a linear scale just like time and space, and that on this scale, humans would place their "1 to 10" tick-marks in a logarithmic spacing, as in the earlier picture, the same way that innumerate tribes do with their number words. * This is unlike, for example, eye color, where only a few genes make most of the difference, and where eye color is mostly a recessive trait. That is, most people have dark eyes and only a few have light eyes -- whereas a normal distribution of eye color would show most having green and equal, smaller numbers having blue or brown. Labels: babes and hunks, Genetics

Monday, August 11, 2008

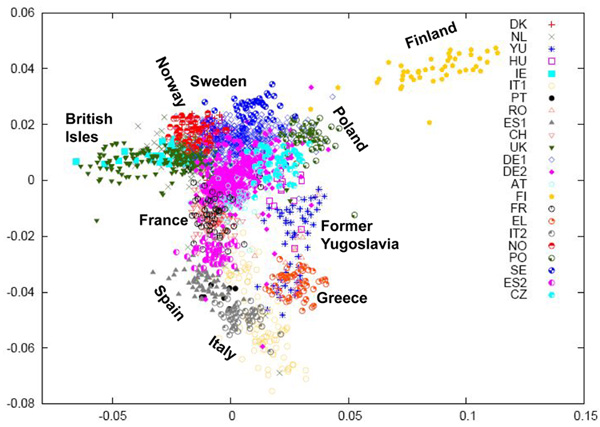

European population substructure...Finns in the corner again

posted by

Razib @ 8/11/2008 01:23:00 PM

Dienekes has a long post on a new paper, Correlation between Genetic and Geographic Structure in Europe. I took the figure and decided to just label the geographic provenance of the primary clusters which emerged when one plotted them along the two largest dimensions of variation (Y axis is 1st component, X is 2nd component) for easy gestalt absorption. To a large extent genetics does seem to follow geography. Obviously the labels for Italy and Spain really underestimate the area these two samples span, so they are meant to be general pointers, not precise indicators of the center of a given cluster. Note Finland...too terrified to join the party I assume? Dienekes has a long post on a new paper, Correlation between Genetic and Geographic Structure in Europe. I took the figure and decided to just label the geographic provenance of the primary clusters which emerged when one plotted them along the two largest dimensions of variation (Y axis is 1st component, X is 2nd component) for easy gestalt absorption. To a large extent genetics does seem to follow geography. Obviously the labels for Italy and Spain really underestimate the area these two samples span, so they are meant to be general pointers, not precise indicators of the center of a given cluster. Note Finland...too terrified to join the party I assume?Update: Also, see what Sandman sayeth. Update II: And Genetic Future. Labels: Finn baiting, Genetics

Wednesday, August 06, 2008