|

Sunday, May 31, 2009

Tyler Cowen explains "Why Steve Sailer is Wrong." For regular readers of GNXP, the resulting discussion is neither new nor interesting, but I thought it valuable to go through Cowen's post in detail. Cowen is a smart guy with interesting things to say about many topics. Why is he so flummoxed by this one?

Cowen begins:

That's a reasonable way to begin the conversation, but if you are going to mention Sailer's name in this context, a) You ought to give a brief summary of his views and b) Provide a link or two. Sailer believes that "race" and "IQ" --- like "atom" and "species" --- are scientifically meaningful concepts and that human races differ, on average, on many dimensions of interest, including IQ. Why couldn't Cowen begin with that simple sentence? Cowen continues:

1) It is good to see that Cowen does not deny the reality and usefulness of "race" as a scientific concept. Recruiting folks like Cowen should be a high priority for believers in human biodiversity (HBD). 2) The phrase "intrinsically inferior" is about the worst possible phrasing. Why can't Cowen use simpler language? Sailer thinks that average IQ differs by race. East Asians have, for example, higher average IQs than whites. Using the word "inferior" is misleading since it implies distributions that don't even overlap. Sailer believes that the averages differ. He acknowledges that many, many individual whites are smarter than many, many individual East Asians. The adverb "intrinsically" is also unhelpful. Does Cowen define "intrinsically" to mean "genetically?" Although I am no Sailer expert, I suspect that his position would be that the genetics of the issue are largely besides the point. Even if the causes of racial differences in IQ are 100% environmental, those differences are still there and, at least by adulthood, they are unalterable. So, public policy needs to take account of those differences. And, if anything, Sailer seems to be more environmentalist than many in the HBD community, recommending policy changes like increased iodine and other micro-nutrients in the food supply of African countries. 3) Cowen's usage of the term "now-unpopular" is interesting. It depends a lot on the unstated "among whom." Certainly, Sailer's views are highly unpopular among, say, the George Mason faculty. But Cowen is, if nothing else, a globalist. Does he think that Sailer's views are unpopular in China? If anything, Sailer would be a moderate among the Chinese. 4) Cowen writes as if there is a conflict between the within and between races decomposition of IQ differences. Note the use of "instead." But he offers no evidence that he and Sailer disagree. And what is the nonsense about "traction?"

As josh notes in the thread:

Cowen is too smart to take that bet, or a bet about the racial distribution of SAT or GRE scores next year, or even decades from now. Cowen thinks IQ is "multi-dimensional." So say we all. The results of an IQ test are not marked on an iron bar in Paris, like the original definition of a meter. They are imperfect. Yet this is a post that is supposed to explain "Why Steve Sailer is Wrong," and yet Cowen offers no evidence that he and Sailer disagree about the meaning or dimensionality of IQ! Cowen:

So what? This is more irrelevant hand-waving. Cowen is supposed to be arguing that Sailer is wrong about race and IQ, not that Sailer is wrong about "the role of IQ" or "neurodiversity."

What do you mean by "you," white man? Notice the strange second person construction, quite unlike the rest of Cowen's prose. He is able to address almost all other topics by describing either what is true or what he thinks. Why bring "you" into it? Why can't he just tell us what he thinks? Some nations have higher average IQ than other nations. Cowen is unlikely to make progress in his case against Sailer if he can't even manage to describe reality in simple declarative sentences. And, although there is a high correlation between IQ and GDP, this was less so in, say, 1960. Does the rise in economic wealth is Asia support or refute Sailer? Cowen declines to discuss that natural experiment. Moreover, Cowen can't even seem to suggest the obvious long term bets that a serious consideration of Sailer's position would suggest. There has been minimal economic progress in sub-Saharan Africa since the end of colonialization. Those who believe, like Sailer, that the average IQ in many of these countries is 85 or so would argue that there is unlikely to be any progress in the next 4 decades either. Indeed, it is hard to see how any country can avoid utter ruin. Sailer might forecast that South Africa will go the way of Zimbabwe. Or perhaps not. The key point is that if Cowen wanted to take seriously the notion that countries differ by IQ and that this fact matters for the future, there are all sorts of bets he might offer. Instead, he gives us nothing of substance. Cowen continues:

"It is sometimes noted" by whom? Again, the entire style of this post is quite different from Cowen's typical contribution to Marginal Revolution. If someone is noting something, why doesn't Cowen provide a link or at least tell us their names? It almost seems like Cowen is familiar with the relevant literature but does not want his readers to know just how familiar. The easiest way to get Watsonized is to make too clear how deeply you have drunk at the fountain of forbidden knowledge. Note, also, that the fact that scores can continue to rise is largely besides the point. Sailer does not dispute the Flynn effect! So, whether or not Cowen finds it more (or less) significant than Sailer is irrelevant.

1) There is some evidence that the Flynn effect has stopped, so talk of time on an "improvement track" may be pointless. Further discussion here. 2) But, again, Sailer agrees with all of this! (Or, at least, he can grant all of this without backing down on his main thesis.) When is Cowen going to explain "Why Steve Sailer is Wrong?"

So what? Sailer does not deny that racism exists or that it is harmful. This sounds like more throat-cleaning to preserve Cowen's place in the commentariat. As "tom" in the comment thread notes:

Good question. Back to Cowen:

So, the key issue is comparing the harm caused by "hypocritical discourse about race" versus the harm caused by racism? What relevance does this have to the issue at hand? Another Marginal Revolution commentator notes that "This thread is almost a rehash of one at Brad DeLong's blog back in 2005! Brad was caught censoring comments, including ones by Greg Cochran and Steve Hsu." Indeed, see the provided links here, here and here. Summary: Cowen's post about "Why Steve Sailer is Wrong" is pathetic. He fails to clearly explain what Sailer believes or to offer arguments against those beliefs. He seems familiar with some of the relevant scientific literature, but declines to mention any of it. Cowen is trapped. He is too intellectual honest and open-minded to ignore the issue completely but too aware of the dangers of being Watsonized to dare to address the topic of race and IQ directly.

Two papers in Nature Genetics report today that variation in KITLG is associated with development of testicular germ cell tumors. Regular readers of this site will recognize that gene name: KITLG is also one of the important loci contributing to differences in skin pigmentation between human populations. The authors are aware of this:

As KITLG has a role in determining level of pigmentation, we postulated that inherited variation at this locus could provide a genetic explanation for the observed differences in TGCT incidence in whites and blacks. KITLG has undergone strong positive selection in the European and East Asian populations, with an extended haplotype of 400 kb. Data from HapMap phase 3 show significant differences (P = 4.3 times 10e-20) in the frequency of the risk alleles of KITLG (rs3782179 and rs4474514) when comparing the CEU (major allele frequency = 0.80) and ASW (African ancestry in Southwest United States: major allele frequency = 0.25) populations. This finding suggests that inherited variation in KITLG may explain, in part, the observed differences in TGCT incidence between whites and blacks.This makes for quite a nice story--selection for lighter pigmentation in Europeans appears to have led to the increase in frequency of a linked variant that causes increased risk of TGCT. As we understand more about the genetics of human traits, I suspect that examples like this--where traits are correlated due to selection on one impacting the other simply due to physical proximity--will become rather common.

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Austin Bramwell has a piece up where he focuses on Spengler's (David Goldman, not the original Oswald Spengler) intellectual hero Franz Rosenzweig. Bramwell suggests:

I consider only the political implications of Star, of which, surprisingly enough, I find very few. The Spenglerian theses in particular seem more like a creative gloss or "misprision" of Rosenzweig than an accurate restatement of his views. For all Spengler's obeisance to Rosenzweig, I suspect that Goldman came up with his stuff on his own. Star is Rosenzweig's book The Star of Redemption. The link is to Google Books, so you can read a fair amount before you hit the preview limit. GNXP reader TGGP pointed out an obvious Spenglerian dishonesty a long time ago. Just as Bramwell suggests that Spengler's oeuvre has far less to do with Rosenzweig than he might represent, TGGP found an instance where he cited as a support for an argument a footnote which didn't support his argument if you actually read the original source, which most of his readers obviously would not. All of this matters because I occassionally get emails from big fans of Spengler who want me to give a response to this column or that, and sometimes he is brought up as an authority in the comments. He's also cited by people who I believe to be sincere seekers of truth such as Rod Dreher. But frankly the kind of thing TGGP put the spotlight on isn't surprising, when people point me to an "awesome" Spengler column there's a lot of smoke and mirrors, and the intellectual equivalent of "card tricks" pop up over and over. This doesn't mean the conclusions he reaches are necessarily incorrect, and if a plate of shady facts is your cup of tea if that's what you need get to dessert, I say go to town. I generally pass when that's on the menu. Look at this catch by Steve from several years ago. Spengler's assertion is pretty much a joke on the face of it factually (read The Reformation by Diarmaid MacCulloch for why you should be laughing), but 99% of his readers wouldn't know that, so they will continue to follow his close reasoning from false premises. His columns are mind-numbing because they're riddled with this sort of misinformation. Labels: Spengler

I already pointed to Scitable on my other weblog, and I thought I would here too. It's a new education oriented site put out by Nature which is currently focused on genetics. The topics section is pretty good for a more-deep-than-Wikipedia but not-quite-a-research-paper level stuff. They do have a "feedback" option, but I really think they might benefit from having a comment feature which can be hidden. There's a lot that can be learned about a subject from the various debates people have about specific terms (this sort of feeback occurs in Wikipedia discussions).

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

God Is Back, John Micklethwait & Adrian Wooldridge don't know what they're talking about

posted by

Razib @ 5/27/2009 08:44:00 PM

Rod Dreher points me to a John Gray review of God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World. He criticizes the supply-side model of religion which John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge are promoting and assume as a given. The model's exemplar is the American South, where people basically "shop" for a church, which can be considered a "firm," offering a unique set of particular services which allow for brand differentiation (if you're poor and like to be entertained, join the Holy Rollers, if you're rich and want to network, join the Episcopalians). The model hasn't been totally supported, it's a theory, so you need to test it. It doesn't seem, for example, that Eastern Europe has been converted to it despite the post-Communist boomlet in evangelical Protestantism. Rather these societies have remained staunchy secular (e.g., Czech Republic) or shifted to a cultural-cartel based system common in much of the world (e.g., Russia). In societies where the supply-side model has flourished, such as South Korea, it turns out that the logistic curve hit "saturation" around ~50%, which was not a prediction of the model since denominations will emerge to fill the preferences of nearly everyone in a society.

In any case, that's not the main reason I'm posting this. Micklethwait and Wooldridge know about publishing and selling books, the thesis is what one could charitably term as "provocative," and surely angry secularists and heartened religionists might make impulse purchases at the bookstore to see what the authors are claiming. But there's a problem: the authors don't have a good grasp of the topic they're presuming to cover. They seem to have the same level of fluency as someone who reads the religion sections of major world newspapers, or makes sure to jot down the religious affiliation of a newsworthy individual or group. If this is your level of understanding you'll be mislead, since you won't know enough to figure out that they're out of their depth. A scholar such as Philip Jenkins produces much better popularization of the topic because religion is something he actually knows in depth, as opposed to being the current flavor of the month he's reporting on. If you read a Philip Jenkins book you'll encounter data which you can't find in The New York Times or The Economist. Also, it's important to remember that Wooldridge and Micklethwait are pushing foward an American model of religiosity when the United States is going through a wave of secularization. The data were obvious as far back as 2000, when the American Religious Identification Survey showed an enormous amount of disaffiliation, but it's been verified by a lot of work in the past few years. I suspect that Micklethwait & Wooldridge started writing the book before the more well known results, and so had to run with the ball. Of course it could be that they know their simplifications are going to mislead people. But I doubt it. Note: I do agree that the American/supply-side model is becoming more common across the world, but that doesn't mean it will become ubiquitous in the coming years. There are regions of the United States even, such as Utah, parts of the Upper Midwest and New England, which seem to follow different systems. Labels: Religion

To Protect an Ancient City, China Moves to Raze It. The city is Kashgar, in the far west of China. I have read that Kashgar is the large city furthest from oceans on all directions. It's a typical story of developers wanting to develop. You read articles like this about Beijing all the time (or did, I assume that most of the developing to be done has been done). One issue that I'm curious about though, my understanding is that China (and East Asia in general) has fewer buildings of great antiquity than in the West because so much of the monumental architecture was in wood. This results in ancient cities being viewed as relatively ephemeral, with the elements (especially fire) taking what humans don't eventually tear down and reprocess. So there is very little of the earlier dynasties in the old imperial capital of Xi'an because the complexes of the imperial family and aristocrats were made of wood. Perhaps some of the reporting of how heartless Chinese bureaucrats are in regards to historic buildings suffers from a cultural gap whereby societies which materials like stone assume more permanence to architecture than those which rely in less durable medium such as wood.

Labels: Central Asia, culture, History

Your Lying Eyes looks in the GSS to resolve the question above. Looking in the GSS is obviously a mitzvah in my book, as John noted in The Corner today. 6 months ago Kevin Drum promised some GSS blogging in the future, but doesn't look like he's gotten around to it. In any case I asserted below that the human mind is a slapdash ad hoc rationalization generating machine. Since human behavior is in large part a function of the human mind, the same applies to it. This is why I love the GSS; deducing likely sociological patterns from a priori assumptions and facts is not impossible, but it's a real dicey proposition. The empirical data is essential to double-check inferences which seem plausible. And of course, deduction relies on that sneaky prefrontal cortext again, which is liable to play shell games with "logic" until it gets the conclusion it wants. The difference between possible and plausible in the minds of most maps onto normative frameworks rather suspiciously from what I can tell. You can play games with the GSS too by manipulating the interpretation (ignoring obvious confounds), but since the methodology is relatively transparent it's harder to get away with it if you aren't preaching to the choir.

Addendum: Poking through the GSS is actually very easy and doesn't take much time when compared to spinning theories based on personal intuition. So why is the latter still so much more popular than the former? Because theories derived from intuition are easy to verify via personal "thought experiments" or experience. In fact, these experiments always support the theory and rarely falsify them! Labels: GSS

The first is for science weblog posts. Nominations end the 1st of June. Steven Pinker is picking the winner out of 6 finalists.

Labels: Blog

Look before you leap: Are women pre-disposed to be more risk averse than male adventurers?:

"It's not at all that women are risk averse," says Jody Radtke, program director for the Women's Wilderness Institute in Boulder, Colorado. When men are confronted with challenging situations, they typically produce adrenaline, which is what causes them to run around, hollering like frat boys at a kegger. An adrenaline rush is a good feeling, but when confronted with the same situation, women produce a different chemical, called acetylcholine. The above was originally published by Women's Adventure Magazine. The last reference is to the repeated finding that non-shared environment matters a great deal but isn't well accounted for. Obviously both men and women vary in terms of psychological attributes, and there have been plenty of attempts to adduce the variation to different quantities of neurochemicals (the "chemical soup" model is easy to translate into prose). The content of the piece isn't too surprising, you see it all the time. Suggesting innate differences between men and women is totally acceptable so long as it is perceived to be neutral, or, better yet, casts women in a positive light. Michael Lewis' recent article on the Icelandic financial turmoil hints to sex differences and male psychology as a root problem. He presented a rather conventional stereotype of men as financial cowboys willing to take outsized risks for reward, while women were risk averse socialists. During the run up to the Iraq War and afterward I recall many people, mostly but not always women, calling into Leftish radio shows promoting a sex determinist theory that war was the result of the male nature, and the fact that men are head of states of most nations was the ultimate problem (this argument crops up in science fiction as well). The interesting point to me is the sort of articles which highlight "different ways of thinking" between the sexes and how they might be rooted in biological differences have implications which point in different directions in terms of positive or negative valuation depending on your perspective and circumstance. As a specific example, the risk taking predispositions of many males can be seen to be folly and lack of prudence, but, risk often entails both an upside and a downside. Decisions which may seem foolish and wrongheaded viewed through a conventional mainstream lens are often lauded in hindsight as visionary. Unfortunately the nature of uncertainty is such that one has little idea which risks will pay off and which will simply extract a downside cost. It is likely that human societies dominated by those who are only risk averse, or those who are only risk accepting, would not be those which we would truly wish to live in. Variation in human personalities is probably beneficial in an aggregate sense when it comes to human progress. There are downsides risks to both the risk averse and risk accepting strategy, so it is probably best to have some of both. In an economic scenario what I'm talking about is straightforward; consider two individuals with degrees in computer science, one who goes to work for IBM and another who founds a start-up. You wouldn't want everyone to aspire to become a corporate employee, where would the innovation which drives productivity growth come from? On the other hand, there are only so many start-ups which succeed and there is a need for individuals who work in less sexy sectors who service older established technologies which are at the heart of the current economy. In other words, you want to be able to squeeze more juice from the oranges you have, as well be funding research which might result in the discovery of jucier varietals. Addendum: Obviously what I'm saying here isn't too novel. It's rooted in human nature itself: our minds are cobbled together from disparate competencies and subfunctions, and our unitary consciousness is a delusion very successfully promoted by the prefrontal cortex. But even when it comes to concepts and assumptions which are the purview of the prefontal cortex its priority isn't usually to keep its story straight. Rather it seem geared toward generative ad hoc narratives which are only proximately consistent. Yes it can engage in rationality, but most of the time its forte is rationalization. And why not? Rationalizing the contradictory feels good! It was almost certainly highly adaptive in the past, and likely is today, in terms of keeping everyone in the group on the same page. Labels: Genetics, human biodiversity, sex differences

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

The journal of record, Texting May Be Taking a Toll. WTF? I recall there were articles years ago about addiction to email, the web. Now also social networking sites. Is this just a general phenomenon that whenever new technologies appear that teens are enthusiastic about the media will play up fears of how it might be dangerous or deleterious? Do people remember stuff about how widespread usage of telephones were going to cause problems too?

Saturday, May 23, 2009

NOTE: I had a couple typos in my equations in the original. This is updated and fixed, and hopefully totally correct. Thanks to bioIgnoramous for pointing it out.

Over at Scienceblogs, people are talking about waves. Of course, everyone thinks that waves are in the domain of physics, and people always forget about one of my favorite subjects: waves of advance. Way back in the day, RA Fisher wondered what might happen if genes had to spread not just locally but across space, and he published his findings in a landmark article called The Wave of Advance of Advantageous Genes. This paper was not just important for its contributions to population genetics, but because of fundamental contributions to applied mathematics. As far as I can tell, Fisher and the great mathematician Kolmogorov published similar findings on this same subject in the same year. To that end, these kinds of waves of advance are often referred to as "Fisherian" waves. What was Fisher's model, what did he find, and how has it been extended? Fisher assumed (without much justification) that genes should diffuse through a population, much like dye diffusing through a glass of water. In addition, at each point the dynamics would be affected by natural selection. This led Fisher to writing down a partial differential equation:  Where p is the frequency of the advantageous allele, t is time, and x is space. The parameter sigma^2 is the varaiance in the parent-offspring distance, and s is the selective advantage of one allele over the other. He then assumed that the solution had the form of a wave of stationary shape, and was able to derive a necessary condition on the velocity, namely that the velocity is at least  This showed that even though a gene can sweep through a local population relatively quickly, e.g. ~900 generations to go from a frequency of of .01 to .99 with a selective advantage of 1%, it will take a while for it to spread spatially. That same gene will take an additional 250 generations to fix, say, 50 meters away, assuming parent-offspring variance of 2 meters^2 per unit time. An interesting observation, at least. But what's particularly interesting are some extensions of this work. One of the major extensions comes when the "reaction" term is changed to something just a little bit more complex:  Where the p with the triangle on it, called "p-hat" by those in the know, is an internal equilibrium. What kind of biology might be relevant to this situation? Well, that equation is one way of expressing the famous allee effect in ecology, which describes populations who have lowered growth rates both when the population is large (too much competition, for example) and when it is small (it's hard to find a mate). In evolution, it was thought that that equation could describe the phenomenon of hybrid zones. In another landmark paper, NH Barton described The Dynamics of Hybrid Zones (unfortunately not open access). Now, to be quite honest, I have no idea what Barton is doing in this paper---he's using methods from physics that I'm not really familiar with. Nonetheless, he proved that if the internal equilibrium is too large, specifically if p-hat is bigger than 1/2, then the wave of advance stops dead in its tracks. It can also be stopped by steep changes in population density, among other things. This result is pretty cool: it seemed to explain why some hybrid zones moved, and why some hybrid zones stayed in their placee. Unfortuantely, hybrid zones probably AREN'T described by the simple dynamics above. But we can use that simple equation to learn a lot of stuff about them, nonetheless!

Friday, May 22, 2009

The Science of Fear, and some data on media overhyping of crime risks

posted by

agnostic @ 5/22/2009 02:10:00 AM

Since the world started falling apart, books on how crazy we are have never been more popular. Most focus on findings from behavior economics that show how human beings deviate from homo economicus in making decisions, and The Science of Fear by Daniel Gardner is no different. Unlike the others in this newly sexy genre, though, he doesn't look at economic decisions very much, but instead on how we assess risk -- sometimes to our own harm. Consider those who, in the panic after 9/11, switched from riding airplanes to the more dangerous mode of cars and died in car crashes.

I won't review the book at length since it's an easy read and well written -- worth adding to your "crazy fucking humans" summer reading list. For a taste, though, here's the author speaking on The Leonard Lopate Show. Gardner spends some time discussing how outta-whack the media coverage of a problem is with the underlying risk, as when silicone breast implants for awhile appeared to be the next cigarette or trans fat. Over at my personal blog, I put up two entries that have graphs showing, from 1981 to 2007, the per capita rates of homicide and forcible rape (risk), the fraction of all NYT articles that mentioned "murder" or "rape" (coverage), and the coverage-to-risk ratio (overhyping). Here's the homicide post and the rape post. In both cases, sometime in the early-mid 1990s, in the wake of a generalized hysteria -- identity politics, L.A. riots, Third Wave feminism, blaming AIDS on Regan, etc. -- the overhyping starts to take off and has remained high up through recent years. We've never been safer, yet we've only grown more paranoid. Labels: Behavioral Economics, crime, culture, Media, News

Thursday, May 21, 2009

Genes, Brains and the Perils of Publication:

I have no wish to criticize these findings as such. But the way in which this paper is written is striking. The negative results are passed over as quickly as possible. This despite the fact that they are very clear and easy to interpret - the rs1344706 variant has no effect on cognitive task performance or neural activation. It is not a cognition gene, at least not in healthy volunteers. Labels: Genetics

Tone Language Is Key To Perfect Pitch:

In a study published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America and being presented at the ASA meeting in Portland on May 21, Deutsch and her coauthors find that musicians who speak an East Asian tone language fluently are much more likely to have perfect pitch. The abstract makes it a bit clearer that East Asians who do not speak a tonal language are no better than Europeans. Labels: Genetics

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

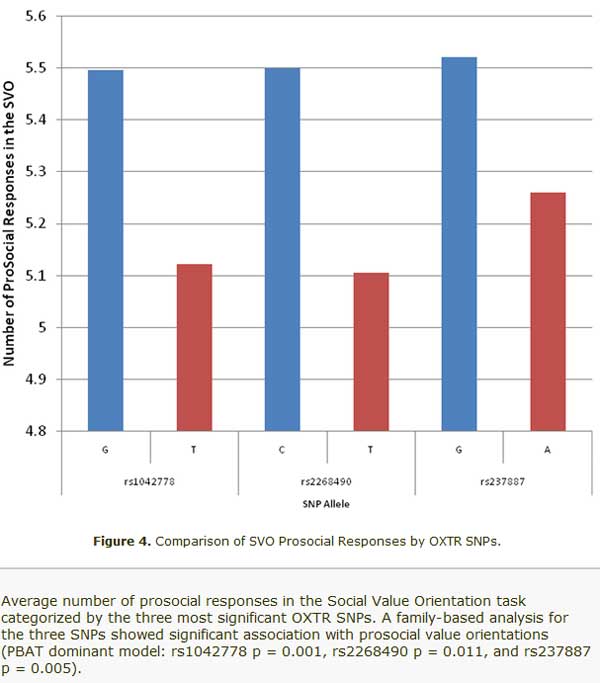

The Oxytocin Receptor (OXTR) Contributes to Prosocial Fund Allocations in the Dictator Game and the Social Value Orientations Task:

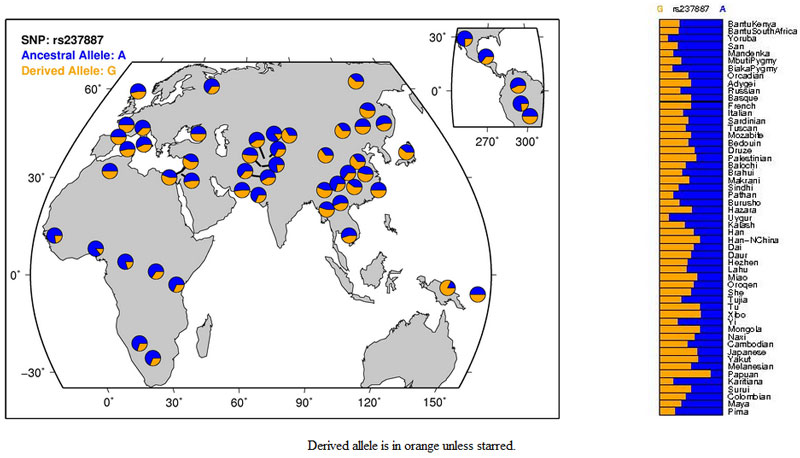

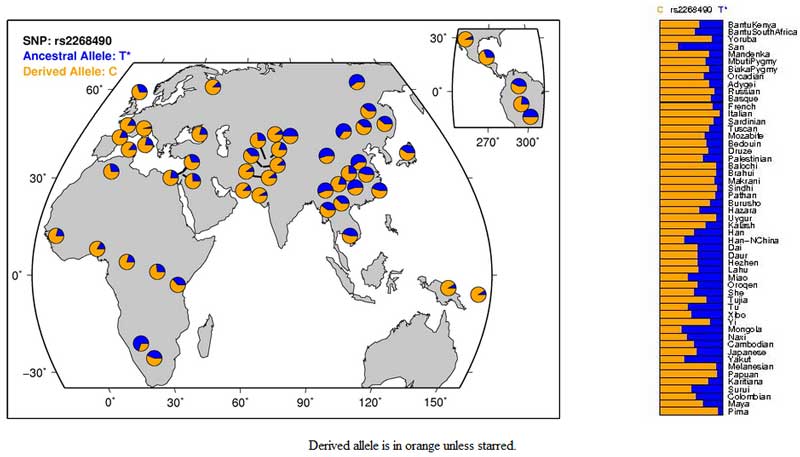

The demonstration that genetic polymorphisms for the OXTR are associated with human prosocial decision making converges with a large body of animal research showing that oxytocin is an important social hormone across vertebrates including Homo sapiens. Individual differences in prosocial behavior have been shown by twin studies to have a substantial genetic basis and the current investigation demonstrates that common variants in the oxytocin receptor gene, an important element of mammalian social circuitry, underlie such individual differences. Here's a figure from the paper:  And the SNPs from the HGDP (G = C & A = T for the first SNP, or at least the paper and PubMed agree on this):    Related: It's hard out here for a vole. Heritability of the Ultimatum Game. Altruism and Risk-Taking: Kinda Heritable. Can someone put the psychic unity of makind out of its misery? DRD4, politics & friendship. Labels: Behavior Genetics, Behavioral Economics, Genetics

David Frum has a very interesting review of How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. In it he touches upon two other works which address the same topic, The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization & The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. I've read them both, and they are excellent histories, though as Frum notes they take different tacks. The former taking a materialist perspective, and the latter a more classical narrative of politics and government. I also agree that to some extent modern multiculturalism has fed into the revisionism which suggests that there was no decline from Classical to Late Antiquity. In From Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its Opponents conservative historian David Gress actually shows how pre-multiculturalist liberal intellectuals, such as Will Durant, privileged pre-Christian antiquity, in particular Greece, and excised the entire period after the fall of Rome and before the rise of the Enlightenment (with a nod to the Renaissance) as making any substantive contribution to the liberal democratic consensus

Where you stand matters in making these sorts of judgements. For obvious reasons Catholic Christian intellectuals of what we term the medieval period did not view the ancient world as superior to their own, because whatever its material or intellectual merits, it was a fundamentally pagan one at its roots. Though the modern West is still predominantly Christian in religion, that religion no longer serves as quite the core anchor that it once did,* and material considerations as well as abstractions such as "democracy" and the "republic" are given greater weight than they once were. I believe that David Gress is right to suggest that attempts by secular liberal historians to deny the essential role of Christendom, the period between antiquity and the age of the nation-state, was driven more by politics than reality. The founders of the American republic were obviously classical educated and that influenced their outlook, as evidenced by their writings as well concrete aspects of culture such as architecture. But they were also heirs to a tradition which defended the customary rights of Englishmen, rights which go back ultimately to Anglo-Saxon tribal law. It is simply laughable to imagine that Greek democracy slept for 2,000 years and reemerged in the late 18th century in the form of the American democratic republic. But, the very same historical factors which make Western civilization what it is today also result in a set of normative presuppositions that does naturally marginalize or diminish the glory of medieval civilization set next to its classical predecessor. Also, one minor point. Frum says: ...Some scholars have speculated that the empire was depopulated by plague after 200. (William McNeill wrote a fascinating history of the global effects of disease, Plagues and Peoples, that argues for disease as a principal cause of Roman decline. In regards to the hypothesis of demographic decline due to plague, the fact that only Claudius II Gothicus died of this cause is likely a weaker point than one might think. Only one monarch died of the Black Plague, which most historians assume killed 1/4 to 1/3 of Europeans. This is probably most easily interpreted in light of the reality that the elites are relatively well fed, and might therefore have been less susceptible to disease than the populace as a whole. The connection between poor nutrition and a relatively anemic immune response to disease has been offered as one reason why deadly pandemics were much more common in the pre-modern period, when a far higher proportion of the population was nutritionally stressed. H/T Conor Friedersdorf * I think the Islamic world is a better model of how medieval Christians might view their classical pagan cultural forebears. Egyptians take pride in the antiquity of their society, but what was before Islam was jahaliya. The preservation of Greek knowledge by the Arab Muslims during the first few centuries of Islam exhibited a strong selection bias toward works of abstract philosophy. Ancient Greece's cultural production in the arts held no great interest, so it is only thanks to the Byzantines that many of those works were preserved. Labels: culture, History, intellectual history

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

I looked at data from the World Values Survey in terms of the actual proportion of those in the age group 30-49 for various countries who have 2 or fewer children, vs. those in that age group who thought 2 or fewer was the ideal number. I aggregated Wave 3 and Wave 4 surveys, so the times range from 1995 to 2002. Data, etc., below.

Now a chart, here's how you'd read it: Top of the Y axis = low fertility in the 30-49 age group (lots of people with 2 or fewer children) To the right of the X axis = nations with low fertility preferences in the 30-49 age group (lots of people who think 2 or fewer children is the ideal) The line represents X = Y. So nations above the line are those where there is more ideal preference for children than the reality, while nations below the line there is more reality, so to speak, than the ideal.  There seems to be a situation where in many nations people want more children than they are having. That is, their avowed preference is greater than what is revealed by their behavior. There are general clusters. The "breeder nations," where people do have many children, but want even more, and the other set where populations are underperforming even their mild expectations. No surprise that the post-Communist nations are in the second category, but interestingly the East Asian nations of Japan and South Korea fall into this range. Interestingly, these are also nations which tend to be rather secular for their social conservatism from a Western perspective. Georgia is not a typo, though I wouldn't be surprised there was a problem with the data (it might be coded or entered incorrectly). Then there are nations where people have more children than they want. Iran has some specific historical conditions which can explain this. During the Iran-Iraq War the Iranian leadership was pro-natalist, but in its wake they have strongly encouraged family planning. Iran is now a sub-replacement nation when it comes to fertility. Vietnam and India have experienced economic turnarounds of late due to their relatively late entrance into the game of globalization. These surveys occurred around the year 2000, about 10 years into both of their liberalization programs. One might be seeing the outcomes of earlier norms overlain upon new mores due to international media. Finally, as far as Bangladesh goes, it is an ethnically and religiously homogeneous nation, so there isn't a national imperative whereby ethnic groups worry about other groups outbreeding them. Additionally, it is very, very, crowded. There are many poor African nations, but aside from Rwanda and Burundi, all of them are far below the Malthusian parameters when it comes to primary production in relation to Bangladesh. Labels: culture, World Values Survey

Skin-Derived TSLP Triggers Progression from Epidermal-Barrier Defects to Asthma:

Eczema (atopic dermatitis) is a common allergic skin inflammation that has a particularly high prevalence among children. Importantly, a large proportion of people suffering from eczema go on to develop asthma later in life. Although the susceptibility of eczema patients to asthma is well documented, the mechanism that mediates "atopic march"- the progression from eczema to asthma - is unclear. We used genetic engineering to generate mice with chronic skin-barrier defects and a subsequent eczema-like disorder. With these mice, we were able to investigate how skin-specific defects predisposed the lungs to allergic asthma. We identified thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), a cytokine that is secreted by barrier-defective skin into the systemic circulation, as the agent sensitizing the lung to allergens. We demonstrated that high systemic levels of skin-derived TSLP were both required and sufficient to render lung airways hypersensitive to allergens. Thus, these data suggest that early treatment of skin-barrier defects to prevent TSLP overexpression, and systemic inhibition of TSLP, may be crucial in preventing the progression from eczema to asthma.

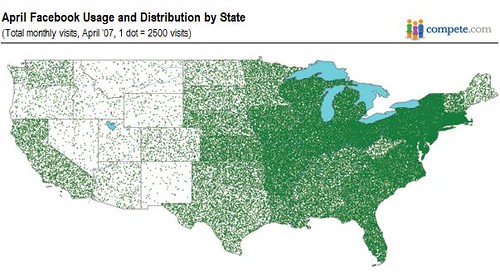

Since most people use online social networks like Facebook to keep in touch with people who they interact with in real life, it doesn't make sense to sign up for a Facebook account unless others in your area have already. This predicts that we should see a spreading out of Facebook from its founding location, just like a contagious disease rolling out from Typhoid Mary's neighborhood. Let's take a look at the data and see.

First, I found this map from Google Images of the number of Facebook visits by state:  Unfortunately, these are not per capita rates. But you can still tell that the Northeast has a whole hell of a lot of activity, while super-populated California shows little. Luckily, Facebook calculated the number of adult users in each state, and divided this by the state's entire adult population size to get the prevalence of Facebook among adults by state. The data are here, and I've made a bubble map of them here. Note that the pattern is pretty similar, even though these are now per capita rates. It looks as though Facebook is spreading from the Northeast, so one easy way to quantify the pattern is to plot the prevalence of Facebook among adults as a function of distance from the original physical site -- Harvard, in this case. (I used the zip code of a state's largest city and that of Harvard to calculate distance.) Here is the result:  Close to Harvard, prevalence is high, and it declines pretty steadily as you branch out from there. The Spearman rank correlation between Facebook prevalence and distance from Harvard is -0.58 (p less than 10^-6). If Facebook were being used to talk anonymously to a bunch of strangers, as with the early AOL chatrooms, then the adoption of this technology wouldn't show such a strong geographical pattern -- who cares if no one else in your state uses a chatroom, as long as there are enough people in total? This shows how firmly grounded in people's real lives their use of Facebook is; otherwise it would not spread in a more or less person-to-person fashion from its founding location. It's not that there aren't still chatrooms -- it's just that, to normal people, they're gay, at least compared to Facebook. Few would prefer joining a cyberworld for their social interaction -- using the internet to slightly enhance what they've already got going in real life is exciting enough. The only exceptions are cases where you have no place to congregate in real life with your partners, such as a group of young guys who want to play video games. Arcades started to vanish around 1988, so that now they must plug in to the internet and play each other online. For the most part, though, the internet isn't going to radically change how we conduct our social lives. Labels: culture, geography, Technology, web

Monday, May 18, 2009

SEED has a set of short video responses to the question "Are we beyond the Two Cultures?", a reference to the split between the arts & humanities types and the science types. Steven Pinker discusses several ways in which the arts can benefit from working with the sciences, such as gaining a better understanding of human attention, visual processing, and so on. In his book The Blank Slate, Pinker argues that one reason that 20th C. art and architecture have been such huge flops is Modernism's denial of a basic human nature, both in terms of how the mind works and what things push our pleasure buttons. But aside from what has been going on in academia and the art gallery world, where does the art-consuming public stand on bridging the Two Cultures?

If we are to believe Tom Wolfe's account in From Bauhaus to Our House, in the first several decades after WWII, most of the elite considered it cool to sit in (or at least display) furniture that embodied the Modernist aesthetic. He emphasizes that Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona chair was particularly sought after. So, some decades later, how much does the public value Modernist design as compared to design whose forms are derived more from nature? (The latter forms appeal to what E.O. Wilson calls "biophilia," or our native apprecation for natural forms. This idea goes back at least to the mid-19th C., when the British architect Owen Jones wrote The Grammar of Ornament, available online in full and in color. It sought to bridge the gap between the arts and the sciences by investigating the general laws of aesthetics in ornamentation, and especially by pointing to the central role that nature-based forms play.) Searching Amazon.com's home & garden section for Modernist keywords "Barcelona chair" gives 957 results (other searches for this item give fewer hits), "Mies" gives 435, "Corbusier" gives 284, and "Eames" (who is much more palatable) gives 1,258. Contrast this with Art Nouveau keywords: "Tiffany lamp" alone gives 10,381, while the broader "Tiffany -breakfast" (to remove Breakfast at Tiffany's memerobilia) gives 16,565 hits. Price differences don't seem to account for this, since the objects from both styles are moderately expensive. The same order-of-magnitude difference shows up for searches of Ebay.com's home & garden section too. "Tiffany lamp" gives 2,003 results, while "Barcelona chair" and "Mies" each give about 40, "Corbusier" gives 303, and the less-insane "Eames" gives 466. Finally, searching AllPosters.com gives 147 hits for "Tiffany" (Studios) and 191 for "Gaudi," compared to only 22 for "Eames," 38 for "Corbusier," and 16 for "Mies." So, as far as the art-buying public is concerned, most people seem to belong to the Third Culture already. It's only arts academics, critics, and others in the business of art who insist on a sharp divide between the arts & humanities and the sciences. After all, they have their territory to defend from the ever-encroaching sciences, whereas outsiders are disinterested. I found something similar when I looked at the under- and over-valuations of composers and of painters as well: most of the art-buying public values mid-late 19th C. music and painting, mostly ignoring the Modernists. When the elite art world abandoned its interest in the sciences, more or less as a fashion statement, it doomed itself to silliness and obscurity. Science types already read a lot outside of their main area, so we don't have terribly far left to go. However, arts & humanities types flaunt their ignorance of the sciences -- unlike Alberti or Owen Jones -- so that the burden of "closing the gap" falls more on them. Labels: arts, culture, science

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Below Razib writes: Though militarily and politically the Song were a subpar dynasty, in terms of cultural and economic production they were exceptional. This is peripheral to Razib's main point in the post, but it's an intrinsically important question which to my knowledge has not been adequately discussed anywhere.

The weakness of the Sung was only relative -- they gave the Mongols as tough a fight as anyone did anywhere, and it took the Mongols four or five decades to conquer South China. I think that the real story is that in North China and Mongolia between 900 AD and 1200 AD (starting with the Khitan Liao) there occurred a military revolution unprecedented anywhere in history. The first part consisted of hybrid steppe-sedentary societies developing hybrid armies combining the advantages of both types of military. Steppe cavalry were highly mobile and probably better disciplined and organized than any previous armies, while the sedentary areas solved the logistics problems nomad armies had always had, and also provided siege engines, infantry manpower, and various sorts of scribes, specialists and technicians. The players were the Khitan Liao, the Jurchen Jin, the Tangut Xixia, the Karakhitan western Liao, the Khwarizmian Turko-Persians, and the Mongols themselves. But note that all of these have hyphenated nomad / sedentary names except the Mongols -- it was the purest nomads who triumphed. What this means to me is that, besides the hybridization revolution, there also must have been some kind of cavalry revolution among the Mongols alone. I have a few ideas about what that might have been: I think that they were ascribable to Genghis Khan himself and consisted mostly of improvements in discipline, organization, and training, but there may also have been improvements in the way cavalry were used. In any case, Mongolia was a military high-pressure zone during this whole era, even more than it always had been. Again and again defeated armies from this region fled to the west and south, often to set up new kingdoms there. The defeated Khitans from North China set up the Central Asian Karakhitai kingdom, which dominated the hybrid Turko-Persian Khwarizmian kingdom in Central Asia (which in turn dominated the Persian and Middle Eastern world as far as the borders of Arabia), but these Karakhitai later were overwhelmed by Naimans fleeing Genghis Khan. And when the Mongols defeated the whole lot of them, the fleeing remnants became a major force in the Levant, fighting for Islam against the crusaders. Even before the rise of the Mongols there had been a definite NE-->SW direction of military flow.

High Blood Pressure Could Be Caused By A Common Virus, Study Suggests:

A new study suggests for the first time that cytomegalovirus (CMV), a common viral infection affecting between 60 and 99 percent of adults worldwide, is a cause of high blood pressure, a leading risk factor for heart disease, stroke and kidney disease. Interesting in light of Jean-Laurent Casanova's research program on genetic susceptibilities to infectious disease. The original paper is here. If many more diseases turn out to be contingent upon infection can the hypochondriacs please get a little more sympathy? Labels: pathogens

Saturday, May 16, 2009

Or is it more like "letting sleeping dogs lie?"

On the issue of that new statue: That Proto-German sex toy is fun enough, but it's time the media stopped elevating things like it as evidence that our species only learned to think abstractly among its subset who, if the lifespan of our species were 24 hours, happened to wander into Europe around 7 PM. Full article here (including swipes at Steve). Labels: linkbait

Friday, May 15, 2009

When I first used Google in 1998 I was amazed. The search experience was qualitatively different. All of my friends who I encouraged to use Google in 1998-1999 had the same experience. WolframAlpha doesn't seem to be in the same league. So the NationMaster bookmark stays. Google:WolframAlpha :: Michael Jordan:Harold "Baby Jordan" Miner? I hope not.

Full-Figured Statuette, 35,000 Years Old, Provides New Clues to How Art Evolved. It's a story based on the new finding of a 35,000 year old "Venus". The sexually explicit aspects are kind of funny, but we've seen technologies such as VHS, DVD and web video streaming being driven by porn in the modern era. Perhaps porn is responsible for a lot more than we think? Something for Geoffrey Miller's next book....

Update: Slate says in relation to the body form the "Venus": Some women in hunter-gathering societies do have abnormally large buttocks, a condition called steatopygia. It's especially common among the Khoisan in southern Africa and tribes in the Andaman Islands. It is sometimes considered a sign of beauty, and may have inspired some of the more voluptuous ancient figurines. The most famous example of steatopygia was the Hottentot Venus, a Khoikhoi woman whose physical characteristics made her a sideshow sensation in 19th-century Europe. Look, this is just an excuse to write an article about ancient obesity and bring up steatopygia. The Egyptians likely never knew anyone who looked like Horus. Labels: porn

Thursday, May 14, 2009

From page 17 of Neo-Confucianism in History:

...Already by the 1050s southerners accounted for the majority of the literary men; within a century southerners would tower over intellectual culture, as they would continue to do for centuries to come. By the 1070s officials from the south had come to dominate policy-making offices. Literati knew this, but in the latter half of the eleventh century they were divided over the solution. Some called on the court to institute regional quotas for the civil service examinations but defended a system that would favor talent above regional representation.... This describes the period of the Northern Song. Though militarily and politically the Song were a subpar dynasty, in terms of cultural and economic production they were exceptional. In fact it is common for historians to wonder why the Song efflorescence did not lead to a Chinese industrial revolution and Great Divergence. In any case, I am struck by the aspects of geographic determinism evident during the Song period, and the analogies one can draw to the Germanic-speaking world in the 17th and 18th centuries as recounted in Tim Blanning's The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe: 1648-1815. While the Rhineland, the Netherlands and north German ports saw the emergence of robust proto-capitalist commercial cities facilitated by cheap water transport, the cities of the Central European Austrian domains still remained primarily centers of royal pomp and bureaucratic administration. The same contrast is clear during the Song dynasty between the inland northern cities, and those urban areas with access to water transport, particularly in the south.

Alan Jacobs, GLADWELL'S GENERALIZATIONS:

Gladwell is always fun to read, but he invariably commits one of the sins we English teachers most warn against when we're teaching freshman writing: he loves to make vast generalizations from one or two particular cases. One obvious point is that a style of play which is effective at one level of athletics may not be as effect at another level, particularly a higher level. Consider the Option or Run & Shoot offenses in football. The Run & Shoot in particular was tried out widely in the early 1990s at the professional level, but most teams gave up on it. Quarterbacks who were statistical monsters in colleges which utilized the Run & Shoot were total busts at the professional level (most famously, Andre Ware and David Klingler from the University of Houston). It turns out that cornerbacks and safeties in the NFL are very fast and athletic, and many college Run & Shoot quarterbacks weren't precise enough in their passing to get the job done. Note: And yes, I'm not even taking into account the reality that professional quarterbacks are enormous economic investments, so there is going to be skepticism about risking such a valuable asset by running options all the time. Labels: Sports

Wednesday, May 13, 2009

Many readers have probably heard that the ACLU has sued Myriad Genetics for its patent on genetic testing on BRCA1/2 (these genes account overall for a small fraction of breast cancer cases, but for many of the strongly inherited cases).

Many companies hold gene patents, so why sue Myriad? The answer is simple: in the battle of public opinion, there's no way Myriad can come out of this looking good. A bit of recent history: the BRCA1 gene was famously mapped by a group led by Mary-Claire King, currently at the University of Washington. That group, however, narrowed down the location of the gene only to a relatively large region, and the gene itself was finally isolated months later and patented by Myriad (BRCA2 came later). Myriad did the obvious--they designed a test for a series of mutations in the genes and began to market it. However, the series of mutations they test is not the whole story--other mutations, untested by Myriad, can cause the disease as well. Other labs would be happy to market tests for these mutations, except, of course, that Myriad refuses to license its patent, preferring instead to hold onto their monopoly on the gene. The result: families that would like to be tested for rare mutations in BRCA1 but an environment in which it is illegal for any company to sell them such a test. It's not for nothing that Myriad is considered among the most hated diagnostics companies. Myriad is probably within their legal rights, but when cases like this get publicity, laws have the funny tendency to change. Labels: Genetics

India: Rural villagers say, "no toilet, no bride":

In Ladravan, a village of farms and brick kilns about an hour's drive from Delhi international airport, one bride has already divorced her groom when she learned that his family lied about having a toilet, says Anil Kumar Chhikara, one of the village leaders. Another young woman, Monica, says of any potential suitor, "I'll be asking him to build a toilet." And if he doesn;t? "Then I won;t marry him."

Life histories, blood revenge, and reproductive success among the Waorani of Ecuador:

The Waorani may have the highest rate of homicide of any society known to anthropology. We interviewed 121 Waorani elders of both sexes to obtain genealogical information and recollections of raids in which they and their relatives participated. We also obtained complete raiding histories of 95 warriors. An analysis of the raiding histories, marital trajectories, and reproductive histories of these men reveals that more aggressive warriors have lower indices of reproductive success than their milder brethren. This result contrasts the findings of Chagnon...for the Yanomamo. We suggest that the spacing of revenge raids may be involved in the explanation of why the consequences of aggressiveness differ between these 2 warlike lowland South American peoples. Perhaps these data are wrong somehow. That being said, I think the "psychic unity of mankind" and an attempt to shoehorn everything into cultural universals led anthropologists, whatever their ideological preferences (or lack thereof) to over generalize about the ubiquity of one optimal reproductive strategy. The data from human ethology about fitness on "small scale societies" can be confusing, it is clear in many cases that the researchers were looking for a particular finding but couldn't validate their expectations. Rather than one model to rule them all it seems likely that a species with such a complex social system as ours does have various niches in which different morphs can optimize their fitness. Greg Clark implicitly assumes this in Farewell to Alms. The martial blood nobility had lower fitness than the relatively pacific gentry up until about 1800 in England because they were killed in war so often. But these patterns also vary over time, Peter Turchin has data sets from Europe which show wild swings in fitness of these martial elites over the past 1,000 years in Europe. When times were good, they were really good (e.g., the Victorian era when the nobility became breeders of the first order), and when they were bad they were really bad (e.g., the War of the Roses when the English nobility "thinned" itself out through conflict). More crassly one has to ask oneself if history is a story of the ascent of the alpha what exactly are the pussies doing hanging around so thick on ground? In a Cartesian manner the very existence of these multitudes refutes the single strategy model. Labels: Evolutionary Psychology

I was in the bookstore and decided to look through God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World. The authors work at The Economist, so I assumed it was going to be more reportage than a popular distillation of scholarship. I haven't read the whole thing, but that seems about right, skimming through I kept picking up errors or tendentious assertions. The very title is, in my opinion, only tenuously rooted in any factual secular trend. Secularization theory's overreach has given rise to a huge counter-literature which argues for the progressively more fervent religiosity of the world. But much of this has little to do with scholarship. Just as George Lakoff knows his audience, and so tailors his "scientific" message in the interests of getting his ideas out there through book sales, so the popular press knows very well that articles and books about the resurgence of religion will sell well. After all, there are many religious people out there. A few years ago David Aikman published Jesus in Beijing: How Christianity is Transforming China and Changing the Global Balance of Power. The book had a natural base when it came to potential sales. No matter that he tended to push highbound estimates for the number of Christians in China, the business is demand side driven.

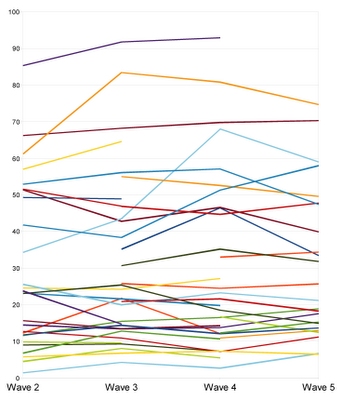

We don't need to talk about China. There's a nation where the mainstream media has been hyping religious revival for the past generation that hasn't been happening: the United States. As far back as the 2000 Religious Identification Survey it was clear that the 1990s were a period of major decline in denominational affiliation. Those data have been confirmed over the past decade. The religious revival in the United States was simply in the minds of hopeful evangelicals, and terrified secular liberals who wanted to hype the power of the religious Right so as to elicit a counterresponse from the Left. And of course cover stories on the rise of evangelical America sell copy (again, scared secularists and enthusiastic evangelicals). So what's the data around the world? Let's look at the World Vaues Survey. There are five "waves" to the WVS, and of these the last four have had a question of the form: For each of the following aspects, indicate how important it is in your life. Religion. The answers are: 1 Very important 2 Important 3 Not at all important Below the fold I've the data from waves 2, 3, 4 and 5 for all the nations. Some obviously don't have data for a particular wave. Wave 2 is from around 1990 (some are as early 1989, with a few as late as 1993). Wave 3 is from around 1995-1998. Wave 4 around 2000. And wave 5 is from 2005-2008. The numbers represent the proportion who agreed that religion was "very important."

Yes, there are almost certainly issues about representativeness across these samples over the years. And the data are spotty. But in any case, there a few cases where we have other sources which confirm the trend line. Spain has become notably more secular over the past 20 years. China has seen an increase in religion over the past 20 years. But I don't see a very strong trend in either direction on a worldwide basis, and I assume a lot of the jumping around individually probably has to do with the nature of the sample . The point is that there hasn't been a massive secular trend in increased religiosity. But who cares? John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge will sell a lot of copies of their book predicated on a likely moronic axiom (judging by the elementary errors that I quickly spotted they don't know much about the topic besides what they read in newspapers). Here's a line graph where I placed all the nations with at least 3 data points. See if you can discern anything from the noise....  I invite readers to weight the data by the populations of these nations and see if, for example, the likely enormous relative increase in religiosity in China from hardly anyone being religious to a small minority being religious is making a worldwide difference. Doing a scatter of wave 2 on wave 5 for those nations which had those two gave an incredible slope of 1.01! Labels: data, Demographics, Religion

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Check out the results (you can also get the data yourself). Here's a sample:

Out of 166 respondees: They really should have asked status re: virginity.

Monday, May 11, 2009

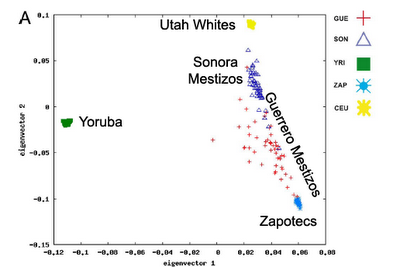

Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico. The title says it all, so I won't post the abstract. The article is OA, so you can read the whole thing, but I thought this figure from the supplements was pretty informative:

Sonora is exactly where you would expect Mestizos to be the most European, while Guerrero on the coast has more African ancestry. See the paper for other Mexican provinces. The use of a Northwest European population is of course somewhat imperfect as the white ancestry of Mestizos is Iberian (though European populations really are not very differentiated in the worldwide context). Additionally, the Zapotecs would be imperfect representative of the genetic variation of all the Amerindians of Mexico (some of whom are likely to emigrated from the American Southwest relatively recently). Sonora is exactly where you would expect Mestizos to be the most European, while Guerrero on the coast has more African ancestry. See the paper for other Mexican provinces. The use of a Northwest European population is of course somewhat imperfect as the white ancestry of Mestizos is Iberian (though European populations really are not very differentiated in the worldwide context). Additionally, the Zapotecs would be imperfect representative of the genetic variation of all the Amerindians of Mexico (some of whom are likely to emigrated from the American Southwest relatively recently).Labels: Genetics, Population genetics

Via Steve Sailer and Half Sigma, we have this New York Times op-ed by David Brooks on work (pdf) by Will Dobbie and Roland Fryer on the Harlem Children's Zone (HCZ). Brooks writes:

No one else seems to have linked to (read?) the study itself. Here are the key graphics:  Extremely impressive, if true. Note, however, that there is no way (that I could find) to tell from the paper just how many observations make up the blue and red dots for 8th grade mean math scores in Fig 3A. Key paragraph:

Using a lottery as a method of randomly assigning students to treatment and control groups is far-and-away the best method for estimating causal effects. Their second statistical strategy, instrumental variables, is much less reliable. If the authors were merely reporting some regression-based estimates, few would take the results that seriously. Teasing out causal effects from a regression is very hard. That the authors do not use a propensity score approach (at least as a check against their estimates) makes me doubt their statistical chops. Anyway, the lottery aspect is key. To their credit, the authors are upfront in admitting that:

I think that the first year of operation refers to 2005, so the number of observations in the 8th grade loser category might be very low. Still, the authors report that "The effect of receiving a winning lottery number is generally larger for students in the 2006 cohort, though we only observe sixth and seventh grade scores for these students and so decided not to show it in our figures." So, I expect that the 8th grade numbers reported here are not a fluke. If you really started with 1,000 5th graders, randomly assigned 500 to HCZ and 500 to their local (lousy) public schools and then saw these huge differences in math scores, you would have discovered just about the biggest causal effect in the history of education research. Have Dobbie and Fryer made that discovery? I don't know. Their write-up and tables make it very hard to understand what is going on. What is the mean difference (without any "adjustments") in 8th grade math scores between students who won the lottery and those who did not? It would certainly be useful if someone were to replicate these results. The notes to Table 2 report that "Each regression controls for the gender, race, lunch status, and predetermined values of the dependent variable." How do you control for "predetermined values of the dependent variable" in a regression? I have no idea. Summary: There are many subtle issues in any study like this one. How do you handle missing data? What about students who win the lottery but decide, for whatever reason, not to attend an HCZ school? The authors mention several of these issues and their approach is reasonable. Still, a lot more focus on the lottery results and a lot less of the instrumental variables would have made for a stronger paper.

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Measuring the shelf-life of student interest in their subjects, using Google Trends

posted by

agnostic @ 5/10/2009 11:55:00 PM

To test how sensitive Google Trends is to fundamental changes in the thing you're asking about, I decided to see if it could pick up the seasonality of fruit availability. Sure enough, it does. Just check blueberries or pomegranate: when the fruits are plentiful, people are very interested in them; outside the peak season, interest plummets. Interestingly, you see something very similar for how much people are searching Google for intellectual topics, which is an indicator of how long their interest lasts.

I noticed a funny cyclical pattern awhile back when I searched Google Trends for slavery. I had a hunch but filed it away. Now I've looked into it, and it's what I thought -- it tracks the school year, specifically when mid-term and final papers are due during the fall and spring semesters. There's sharp drop during Christmas vacation, and a steady low level during summer vacation. To show that this is true, you see the same pattern for postmodernism, Freud, Foucault, semiotics -- plus Darwin, evolutionary psychology, differential equations, and linear algebra. That shows how long the average student, after exposure to some body of thought, retains interest in it over their lifetime -- about a day or so after the exam is done. And intellectual merit hardly seems to matter -- real stuff like differential equations doesn't seem any stickier than the snake oil of postmodernism. If you're an educator who's ever suffered from the delusion that you can inspire lasting interest in your subject, these graphs should wake you up. Sure, there's that one student whose eagerness for the subject is just a bit creepy (unless she's a cute girl, of course), but most of your students will treat your class like they do the movies they see in the theater -- or the Malcolm Gladwell books their parents read -- which provide brief fun but are forgotten a week or so later. This more or less contradicts the proponents of higher ed for everyone, of a core curriculum, and of similar policies that are based on the assumption that students retain anything at all. After their Harvard undergrad educations, most alumni had no clue what causes the seasonal change in weather. (They tend to say that it's due to the elliptical orbit of Earth around the Sun -- summer when it's closest and winter when it's farthest away.) If they're just going to flush out the course's content once the semester is over, why make them take the course in the first place? Except for the school to get their money, and for the professor to keep his job through high enrollment. "But higher ed is not just pre-professional training -- it's about cultivating the garden of their mind!" Well, if the average student were at all intellectually curious, maybe. But most aren't -- once their final paper is in, flusssshhh! To revisit the topic of the education bubble, most arts and humanities majors could cruise through undergrad in two years tops, unless they were dead set on becoming academics, in which case they'd really need to absorb a lot more information. But if you're majoring in history or English in order to go to law school, who cares if you only surveyed one period of English poetry, rather than from Beowulf to the Beats? Obvious exceptions are technical or professional majors, such as engineers needing to know calculus, statistics, etc., which might take them three years to complete. The cold hard reality, shown by the Google Trends data above, is that just about all students are going to junk everything they ever learned in college once they're done with the course -- not even once they graduate. Therefore, having them schlump around all day in these throwaway courses only wastes their time, money, and energy, which could be spent producing stuff. Aside from signaling that they haven't gone braindead or really fucked up their work ethic after high school, a college degree doesn't mean much, unless it's a technical one. So, give them a year or two to prove this, and then get them out into the real world. They'll probably come out the other end of college with healthier livers to boot. Labels: academia, culture, education, too much school is gay

A Genetically Mediated Bias in Decision Making Driven by Failure of Amygdala Control:

Genetic variation at the serotonin transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) is associated with altered amygdala reactivity and lack of prefrontal regulatory control. Similar regions mediate decision-making biases driven by contextual cues and ambiguity, for example the "framing effect." We hypothesized that individuals hemozygous for the short (s) allele at the 5-HTTLPR would be more susceptible to framing. Participants, selected as homozygous for either the long (la) or s allele, performed a decision-making task where they made choices between receiving an amount of money for certain and taking a gamble. A strong bias was evident toward choosing the certain option when the option was phrased in terms of gains and toward gambling when the decision was phrased in terms of losses (the frame effect). Critically, this bias was significantly greater in the ss group compared with the lala group. In simultaneously acquired functional magnetic resonance imaging data, the ss group showed greater amygdala during choices made in accord, compared with those made counter to the frame, an effect not seen in the lala group. These differences were also mirrored by differences in anterior cingulate-amygdala coupling between the genotype groups during decision making. Specifically, lala participants showed increased coupling during choices made counter to, relative to those made in accord with, the frame, with no such effect evident in ss participants. These data suggest that genetically mediated differences in prefrontal–amygdala interactions underpin interindividual differences in economic decision making. Check out the Wikipedia entry on 5-HTTLPR; lots of behavioral phenotypes associated with this variant. ScienceDaily: The researchers also measured the degree of interaction, or connectivity, between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, the brain region most implicated in human intelligence, personality and decision making. When resisting the frame effect, the participants with two copies of the long variant had stronger connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, while those with a pair of short variants did not. So this genetic variation only explains 10% of the variation within the population when it comes to frame effect in behavioral economics. Fair enough. But, I do wonder if in the current political environment fewer would oppose genetically black-balling individuals with the short variants of 5-HTTLPR from becoming traders! (I'm not proposing this seriously myself, but I think there might be some amygdala-driven acceptance of this sort of genetic profiling right now even if the returns are small) Labels: Behavioral Economics, Economics, Neuroscience

Saturday, May 09, 2009

Julian Sanchez has a post up, A "God-Shaped-Hole" Shaped Hole. He notes:

Which brings us around to the core problem with Stuttaford's claim. As James Joyner observes, it's a little doubtful whether the need to worship deities can really be an ineradicable, hardwired human trait when polls show that in much of Western Europe, the proportion of the population describing itself as atheist or agnostic approaches or exceeds the 50 percent mark. This is a common perception, but I'm pretty sure it is also wrong. Sam Harris has described Sweden as an atheist society, while an American sociologist has written of Denmark as a society without God. I think the issue here is that the relative reference frame of the United States distorts the perceptions of American thinkers (combined with the sort of Europeans that they might meet at conferences or at the jobs expats land in abroad). Yes, the proportion of atheists in Scandinavia is on the order of 1 magnitude greater than the United States, but at less than 5% of the population in the United States that is still less than 50% of the population. Below the fold I've put data I gathered from The World Values (limiting to surveys performed from 1995 onward, because of the reality that East European nations exhibited a spike in God belief after the fall of Communism), the Eurobarometer 2005 and a BBC sponsored survey.

I'm pretty sure that the WVS result for Germany is screwed up by some problems with how they weighted the "East German" and "West German" results. There are also certainly some issues with how the question was worded (most surveys show fewer self-described atheists than those who agree with an atheist position in relation to God), as well as the problem of representativeness (it looks to me that for Third World countries like India the WVS is skewed toward a higher SES judging by the levels of education). But you get the picture. Europe and East Asia, unlike the United States, South Asia, Middle East, Africa and Latin America, have a great number of "unaffiliated theists." This shouldn't be too surprising to Americans, the proportion of atheists & agnostics among those with "No Religion" has remained constant for a generation from what I know, at around 25%. Update: Because of questions in the comments I thought I would add the "fifth wave" WVS results from 2005-2008, which had a question which allowed people to sort themselves into "religious person," "not a religious person" and "atheist." Since people tend to avoid the term atheist this is a lowballing of the proportion who don't believe in God. But, because of cross-cultural differences in what it means to be a "religious person," that proportion might also be somewhat deceptive and an underestimate of those who are somehow affiliated with a religious denomination.

Calculated Risk points to this piece in The New York Times about the increased savings rate:

This shift back to thrift may seem to be a healthy change for a consumer class known for spending more than it earns, but there is a downside: American businesses have become so dependent on consumer spending that any pullback sends ripples through the economy. This is a common observation; the American consumer may now reset to a higher level of savings and lower level of consumption, which will cause problems for the sectors of the economy driven by exuberant consumption. What I don't get is this: didn't everyone assume that debt-driven consumption would eventually have to abate? I have read arguments to the effect that the massive influx of capital due to the aging of Japan and the rise of a Chinese savings class enabled the American consumption binge, but that can only go so far for so long. You can't consume more than you produce over the long term, so it seems moot and irrelevant that the American economy has become dependent on this dynamic in the short term. It isn't a downside generated by a choice between alternatives, it's simply a structural inevitability of how the world works that American business can't always depend on increasing levels of consumer debt to drive demand.

Tuesday, May 05, 2009

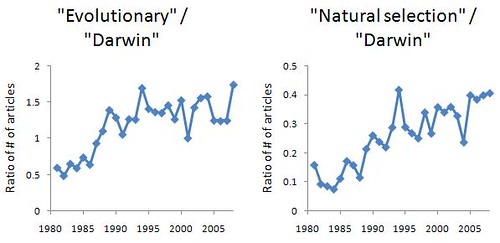

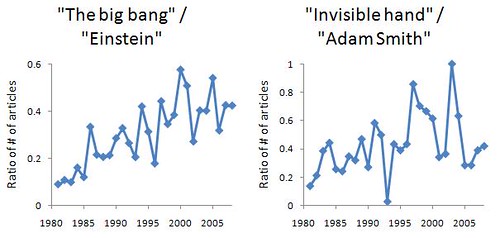

Is news coverage of science focusing more on substance than before?

posted by

agnostic @ 5/05/2009 10:15:00 PM

One thing that many of us worry about is how well educated the educatable public is about biology and evolution -- are they reading superficial stories, or are they being exposed to the deeper ideas? (Set aside whether they'll remember any of it in a few years.) Actually, what most really worry about is whether or not science reporters are doing a better or worse job than before, since we can't really know how much substance the public shoud be expected to grok. There's actually a fairly crude but helpful way to measure this, so let's see what it shows.